The British Columbian Grading Breakdown

How the province’s new Reporting Order collapses and confuses student assessment | Attacks on Excellence, Issue #3

While many students, parents, and teachers experience education as a local phenomenon, the education policy reforms that manifest locally are often parts of broader, international trends. Bryan Joseph is a Canadian teacher interested in comparing the education policy choices he sees in American media to those he sees firsthand. With this look into familiar fights over quantitative assessment — but in new, friendly territory — an American audience might better appreciate how some of the most pernicious education fads are, perhaps unfortunately, not only found in the United States. Thanks for reading another issue of Attacks on Excellence, and the first venture abroad for the series.

Education in British Columbia, Canada

For over a decade, grading and student assessment in British Columbia have undergone a tragic decline. Under the aegis of noble ideals, the British Columbian Ministry of Education advanced curricular changes that made standardized assessment more difficult, and instead of reversing those changes in the face of pushback, the Ministry introduced assessment requirements that replace letter grades and percentages entirely from Kindergarten through Grade 9. Rather than furthering the Ministry’s ideals, the resulting “Proficiency Scale” has flummoxed parents, stressed teachers, and demoralized students.

The story of how reform efforts culminated in the British Columbian K-12 Student Reporting Policy, enacted in select districts in 2019 and province-wide in 2023, traces an all-too-familiar arc of reformers advancing idealistic ends with maladaptive means while performance plummets and alarm bells go ignored.

Because Canada does not have a national Ministry of Education or a unifying set of commonly prescribed learning outcomes, each provincial Ministry enjoys total freedom to set its own educational policy and curriculum. For a province with an affinity for heterodox ideas such as British Columbia, this freedom allows the latest pedagogies to be enshrined in policy as rapidly as they come into vogue. In BC, enthusiasm about new approaches to old problems drowned out warnings against forsaking reliable tools. Sadly, the value of content-based curricula and fair, objective, standardized measures of student learning are sometimes only apparent when they’re gone.

This recent history of education reform in BC has important lessons for those south of the Canadian border. BC shares its cultural penchant for new fashions with the states on America’s west coast. American reforms described in previous CEP posts — such as SFUSD's Grading For Equity initiative — can be better understood through reference to BC's story, both in terms of the motivations that drive them and of the consequences we can expect to follow.

The New Vision

Until the mid-2010s, British Columbian education was grounded in an examination system similar to the A-level qualifications used in the United Kingdom and other commonwealth countries. All students would write provincially standardized Math, Science, and English exams in Grade 10. Students would then choose senior electives and write as few as two or as many as nine subject-specific exams — in Calculus, Literature, Law, etc. — by the end of Grade 12.

As a matter of official record, a student’s “final” course grade was calculated by averaging the provincial exam grade (weighted at 40% for senior exams) with the classroom teacher’s summative grades of in-class tests, projects, and assignments (weighted at 60%). In cases of extreme disagreement between the classroom grade and exam grade, however, the province’s top universities would disregard the classroom grade entirely.1

Provincial exams provided constraint and direction for assessment. Math 9 teachers looked incompetent if their course grades weren't generally good predictors of success in the Math 10 course, and Math 10 teachers looked incompetent if their course grades weren't generally good predictors of success on the Math 10 exam. Examinations kept the system honest, kept the assessments meaningful, and established fine-grained benchmarks for feedback on student progress.

But in 2010, the BC Ministry of Education began a curriculum redesign process that would chart a dramatic new direction for the province. First unveiled in the 2011 BC Education Plan and developed in the following years, the Ministry had a vision of an “innovative education system” centered around two key concepts. The first of these was “personalized learning.” Learning in BC needed to be “focused on the needs, strengths and aspirations of each individual young person”; this meant “acknowledg[ing] that not all students learn successfully at the same rate, in the same learning environment, and in the same ways” and giving students “more of a say in what and how they learn.”

The second key concept was “cross-curricular capacities.” To thrive in the “rapidly evolving world,” schools needed to “do more than help students master the sets of knowledge and skills acquired through the standard subject areas.” Instead, students needed to develop the “core competencies” foundational to all subjects; “a curriculum with fewer but higher level outcomes” would “allow deeper learning and understanding.”

This lofty vision set crucial parameters for the budding curriculum. If teachers and students were to cater learning plans to each individual student’s needs and interests, they would need a “flexibility” at odds with enforcing rigid requirements regarding specific content outcomes. Neither could teachers’ assessments be too rigid; part and parcel of personalized learning was giving educators “more ability to decide how and when each student is assessed.” The flexibility necessary for the Ministry’s new vision led to major curricular changes:

1. A substantial increase in the number of available senior academic electives.

Whereas previously there had only been one History 12 class for seniors, the new curriculum senior would include scope and sequence for Asian Studies 12, Comparative Religions 12, Economic Theory 12, Genocide Studies 12, etc. In total there would be 15 social studies courses available at the senior level.

2. A focus on allowing place-based differentiation.

Since personalized learning placed a lower premium on content outcomes than “increasing student engagement,” Chemistry 12 teachers working in the province's south-eastern region were encouraged to teach a course that centered on examples and applications drawn from the regionally relevant coal mining industry, while teachers on the northwest coast should instead focus on maritime chemistry.

3. An emphasis on process over product.

Teaching to develop students’ core competencies was separable from teaching specific content outcomes. Accordingly, new curriculum documents would contain half as many prescribed learning outcomes for content and fill the space with descriptions of skills and competencies to be developed. English teachers could substitute personal favorite texts in and canonical classics out, so long as they used those favorite texts to explore standard tools of literary analysis. Students were no longer writing essays about World War II for the sake of learning the events and themes of World War II; rather, they were learning the details of World War II as a useful pretext for learning to write essays.

As teachers opted in piecemeal to the new curriculum over a three-year transition, it became readily apparent that continuing the provincial exam system was impossible. The standardized exams stood in tension with the loose place-based, teacher-customized curriculum and the ambition to give educators more say in how their students were assessed. On a practical level, moreover, it would be completely untenable for BC's relatively small Ministry of Education to create quality exams for each and every course semester over semester. As the Advisory Group on Provincial Assessment reported without irony in 2014,

“As the educational system moves away from ‘knowing things’ toward ‘understanding things,’ then it becomes more difficult to determine what should appear on an examination.”

Some stakeholder groups voiced concerns to the Ministry that scrapping the provincial assessment system could imperil the availability of the high-quality data needed to make informed policy decisions. Yet by the time the Advisory Group released its second report a year later, it had become more confident in the BC Education Plan and less worried about such “external” concerns:

“[S]takeholder groups that are external to the K-12 education system (e.g., employers and post-secondary institutions) have commonly relied on graduation data to inform their decisions. While we recognize these “external” needs, we also acknowledge that meeting the needs and purposes within K-12 must remain the primary drivers for assessment, and that the functions of the K-12 system should not be controlled by external needs.”

And so BC students wrote provincial exams for the last time in 2017. In the years since, the only standard examinations in BC schools have been literacy and numeracy temperature checks divorced from any particular curriculum and graded on 3- or 4-point scales. While these generic assessments arguably provide useful data to schools in general, it remains unclear to what use these data are being put — even a sympathetic case study acknowledges that lower quality data had resulted in an “absence of test-based accountability” for schools and teachers.2 Nonetheless, the curriculum persisted, as yet undeterred.

A Crisis of Confidence

The Ministry’s curricular overhaul did not initially change the provincial reporting policy. In the first years without provincial exams, student achievement was still summarized at both course midpoint and end of semester with a percentage score and a corresponding letter grade (e.g., a score between 67% and 73% and an attendant C+). To complement a student’s quantitative marks, teachers were also required to write a brief comment and assign a "work habits" score measuring general conscientiousness. For a time, the curriculum seemed compatible with this combination of comments and traditional marks.

Soon, however, the new curriculum engendered a crisis of confidence in percentage score summary grades, especially at the middle school (Grade 6–9) level. Issues with poorly standardized percentage scores are well understood, both in the literature and by students who’ve been burned by imprecision.

BC teachers were no longer consistent in either the specific content that featured in their lessons or their expectations for how much of that content students needed to remember. When Mr. A covers fewer works and assigns easier projects in his English 9 course than Mrs. B does in hers, our assessments are no longer reliable enough to judge that an 89% from Mr. A indicates greater learning and retention than an 83% from Mrs. B. Once policies and standards came unmoored from clear content requirements, the faith that an “A” or a “B” reflects the same quality of work across schools and time collapsed.

In the US, the Equitable Grading Project watchdog group — which champions the aforementioned Grading for Equity programs — makes an effort to answer these sorts of questions and keep grades transparent, but their methodology depends almost entirely on independent, standardized, subject-specific testing. During the years in which BC enjoyed a standardized provincial examination system, BC teachers could still claim that course grades were intended to be precise and formative predictors of exam performance. Teachers would endeavour to peg their assessment practices to the provincial standard, and over time we got pretty good at this!3

Without the exams, however, course grades on a percentage scale were open to criticism for claiming unjustified levels of precision. With every classroom teacher untethered from a standard, nothing could guarantee that a grade of 83% meaningfully differed from an 81% or 85%.

It was here that BC education reformers faced two paths. The first led back to precisely assessing student achievement: accept that the Ministry’s noble goals had undermined grading and wrought confusion, and, heeding earlier stakeholder pushback, walk back the curricular changes. The second path meant doubling down: hold fast to ideals and, with standardized assessment already destabilized, seize the opportunity to introduce a novel reporting framework that does away with ordinal grades entirely.

Reformers took the second.

The New Reporting Policy

The BC Ministry of Education ultimately determined that the existing reporting policy was a relic that “no longer aligned with key principles of the provincial curriculum.” A new policy had been piloted in some schools and districts since 2017, and — despite a 2021 survey in which nearly 70% of parents and teachers opposed its adoption — it was finally ready in August 2023 to bind every school district in BC.

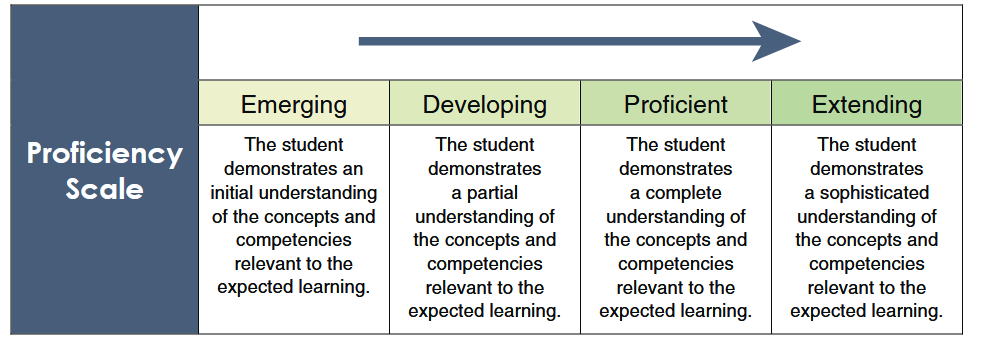

Under the “K–12 Student Reporting Policy,” while letter grades and percentages are still used in Grades 10–12, in Grades K–9 teachers are required to assess student learning using a four-point “Provincial Proficiency Scale": "Emerging," "Developing," "Proficient," or "Extending."

The Proficiency Scale was supposed to offer two central benefits over letter grades and percentages. First was clarity: by assigning students a place on the scale and pairing this assessment with “strengths-based descriptive feedback” “in clear and accessible language,” teachers could “clearly” and “meaningfully” communicate to students and parents what they currently understand and what they still need to learn. Second was motivation: by “shift[ing] the focus from getting marks to developing competencies” and explicitly setting proficiency as “the goal for all students,” the scale would teach students that “learning is ongoing” and would “lead to increased student engagement and deeper learning.”

Neither benefit has materialized.

Students and parents have been badly confused by the four-point scale. While 93% of Canadian parents found an “A” letter grade “clear and easy to understand,” only 42% say the same for “Extending.” Most parents and students struggle to understand what distinguishes the “sophisticated” understanding that earns an “Extending” grade from the merely “complete” understanding warrants a “Proficient.” The lack of clarity in turn makes it hard for parents to know what their children can do to improve from a “Proficient,” especially when “Proficient” is explicitly presented as “the goal for all students.”

When it is not immediately obvious to most parents whether a term like “Developing” is a strong grade or a weak one, the language of the proficiency scale is especially hard to navigate for English Language Learning households. Whereas understanding letter grades and percentages demands only a grasp of alphabetical and numerical order, the Proficiency Scale demands parsing new terms that even fluent speakers struggle to tease apart. While efforts at "educating" parents are underway, most are frustrated that they need to be “educated” in a system they had opposed at all.

Because the four-point scale is far less granular than percentages, students and parents find it more difficult to track incremental improvements. While small but steady increases in study time and effort can be captured by small and noticeable increases in percentage points, it takes much more to shift a coarse-grained scale with only four designations. Students whose regular improvements on previous performance do not deviate enough from ‘the expected level of learning’ will continue to see an unchanging, uninspiring "Proficient" again and again. This has made the new policy incredibly demoralizing for students. Without a means to benchmark small improvements, and knowing that all work will be met with saccharine, strength-based praise, many students fall into patterns of doing the bare minimum.

Ironically, Proficiency Scale proponents have argued that letter grades provide little motivation for high performers to improve when they’re “always going to be the A in the class,” but the same reasoning suggests that a scale that changes even less often would provide even less drive to improve. This widespread loss of motivation is even reflected in the declining participation rates in the purportedly mandatory province-wide assessments that remain.

At the same time that the scale is demoralizing for high-performing students, the scale also makes it harder for parents to spot warning signs for lower-performing students. Worrying that “Ds,” “Fs,” and low percentages discourage low-performing students, policy authors take every opportunity to blunt the edge of the left half of the scale. Parents are reassured that receiving “a ‘Proficient’ in math and a ‘Developing’ in English” does not mean a child “is ‘good’ at math and ‘bad’ at English,” only that “all students have both strengths and areas they are working on.” Lest students or parents worry that any term denotes “failure,” the “Emerging” indicator intentionally blurs the line by including both failing students and merely low-performing ones in the same category. Yet the effect of this sugar-coating is that parents have been blindsided by the discovery that, after three years receiving an “Emerging” with accompanying strengths-based feedback, their child simply couldn't read. In BC as elsewhere, education policymakers prefer smashing thermometers rather than the work of changing the temperature.

Teachers, too, have been frustrated and confused with the Proficiency Scale rollout. By 2023, many of us were embittered that the higher-ups who had first imagined the grand BC Education Plan had left teachers holding the bag. Ministry survey results in 2021 had shown that 77% of teachers themselves opposed the shift to a proficiency scale, yet because more administrators were satisfied, the shift had been pushed through. While certain spokesmen today promote it as a virtue that the new system was “meant to take more energy from everybody involved,” demanding more energy from teachers when we were already in short supply was a recipe for further increasing workload, stress, and burnout. Despite aspirations for our communication to be “concise,” the new emphasis on descriptive feedback means some districts now expect longer report cards, meaning even more time and effort spent reframing any negative traits into strength-based redescriptions. Teachers, moreover, are the ones on the front lines of “educating” disoriented parents about the new terms that we struggle to wield ourselves.

Teacher-facing professional development has stressed that the scale is not simply replacing old grades with new terms. We must not simply assign an “Extending” on the basis of criteria by which we used to assign an A, such as answering at least 90% of problems correctly; rather, “Extending” should be assigned only if, in a teacher's “holistic” evaluation, a student demonstrates true "sophistication" in her understanding of the curriculum. Yet this reliance on “holistic” evaluation invites too much subjectivity for us to be confident in our assessments, and the guideline document offers little help with easing the inter- and intra-school disagreement on the right way to use the scale.

Consider two examples it presents of how a student could demonstrate the “greater depth and complexity” required for an “Extending.” While a student in environmental science could “Extend” beyond mere proficiency by “tak[ing] on environmental activism in their community,” a student in Physical Education could “take on a lead role in teaching other students dance concepts.” These behaviors may warrant true sophistication in one teacher’s holistic judgment, but in another’s they may simply reflect an extraverted disposition and nothing about learning at all.

Ultimately, the failure of the Proficiency Scale assessment system undercuts the original vision for a modern provincial curriculum. The aspirations of tailoring services to student needs, enhancing student engagement, clearly communicating student learning, and improving student competency have each been thoroughly undermined. The language of the scale is less clear than the marks it was supposed to replace, and the descriptive feedback that accompanies this scale provides less useful feedback than the fine-grained measures now abandoned.

Paving with Good Intentions

The BC Provincial Proficiency Scale disaster was not built in a day. It is the apogee of a series of misguided attempts to realize a seductive vision, even as the warnings ballooned. The vision that enthralled BC involved a host of trenchant education myths that appeal beyond its borders, too. The notion that education could be personalized for every student at such a level without compromising on content is one such myth; the notion that transferable core competencies can be developed without accounting for substantial content knowledge is another. Still another is that standardized tests could be replaced with holistic assessments without sacrificing fairness, objectivity, or informativeness. It would be much more convenient if students could gain “deeper understanding” by spending less time learning facts, and if informative data that can hold educators to account were still abundant in the absence of standardized exams.

It is often tempting to tell a just-so story that lays the blame for bad policy on a particular political project. In American contexts, pushes for radical pedagogy are often tied up in identity politics; policies which flatten assessment results are seen as left-coded. This leads to the conclusion that bad policy can be avoided by electing careful and conservative governments.

But the political players in BC don't easily map to American political dynamics. It was the right-wing BC Liberals party (now BC United), in power from 2001 to 2017, who introduced the BC Education Plan in 2011. The lodestars of personalized learning and developing cross-curricular competencies were both seen as key pieces of an economically sanguine initiative to spur innovation, increase worker productivity, and complement a BC Jobs Plan that built on “sound fiscal fundamentals.” Indeed, relying on “the best research we have on child learning and teaching practices” was for BC Liberals a matter of fiscal responsibility, as it would “ensure each dollar is being put to the best use in each classroom.”

An interesting dimension to the political valence of issues in BC education policy is the role of the First Nations Education Steering Committee. The FNESC is a lobby pursuing racial justice initiatives that might be compared to similar US groups focused on social justice, and an emphasis on adopting Aboriginal and First Nations perspectives in the classroom was ubiquitous in Ministry material throughout the transition. Despite its agreements with many of the Ministry’s measures, though, the FNESC remains strongly in favour of robust standardized testing, writing in 2022 that the provincially standardized Foundational Skills Assessments

“are key to identifying system-wide strengths and weaknesses within the education system, and help us to measure and advance equity for students through planning, intervention, and support.”

The political dynamics underlying misguided education reform efforts seem to vary just as much, if not more than, the number of such reforms themselves. Unfortunately, there is no shortage of ideologically informed education research available to support the popular education reforms du jour. And in thrall to studies that confirm their priors, administrators end up resisting pushback and casting aside more trusted methods.

Thankfully, this misdirected assessment reform has never afflicted more than a plurality in British Columbia. Standardized testing is not just fair, objective, and informative compared to subjective assessments — it is popular among BC parents. Although the Ministry of Education endorses a false dichotomy between “deeper understanding” and “the memorization of isolated facts and information,” most parents prefer curricula based on firm content benchmarks. Most teachers were never sold on abandoning letter grades and percentages, either, and had their views held more weight than the administrators’, BC might not have had to learn this lesson the hard way.

Defending excellence in education

Thanks to Bryan Joseph for this first international issue of Attacks on Excellence. Comment below or send us an email if your city, state, town, or school has a tale of anti-excellence you want to tell. You can help us identify national and local threats to educational excellence as we build a record of the policies, practices, and personnel that deserve broader attention. See you next time.

Submit a story idea [here] or email centerforedprogress@gmail.com (subject: Attack on Excellence)

This policy remains on the books at the University of British Columbia for older applicants.

The pressure on school districts to collect and reference data remains strong in BC, and in fact the province hosts one of the largest student information data bases in the world.

Province-wide data on pass/fail exam rates was published and is still available online (see here for 2007). Schools received student-by-student breakdowns comparing exam and course results in detail. In 2007 the predictive power of course grades was strong enough that, for example, the University of British Columbia found that they could generally make admissions decisions based on those course grades without having to wait for exams to be processed.

This gives me more information about the Grading for Excellence stuff. It's not that switching to rubrics has negative consequences per se, just that you can do it in better and worse ways. My confusion was based on my inability to imagine it being implemented this poorly.

I think overall regarding assessment - or more importantly, feedback - the more granular and specific, the better. Percentage grades are only as specific as the questions they report on, which in the case of the exam, is the whole course. Rubrics are rarely granular enough (or specific, the language in them is usually pretty catchall and confusing). Having a simple way to show "Sally understands A, B, ... , BC, BD specific things." and comparing that to grade standard would be good. Sally would know precisely what she needs to work on. This gives me hope that something like Alpha school could work for the masses, not necessarily 2x in 2 hours, but at least kids working in their ZPD, and having reports accurately reflect the things they understand and can do.

I was born and raised in BC. This account completely aligns with my past schooling experience (80s-90s) and what I am hearing from relatives still in Vancouver. Though I have some details to add.

The old provincial exam system was great. Even private school students took the same Grade 12 exams, and the exams were not optional as they are for AP exams. So everyone in the school who was enrolled in the academic subject in question (BC English 12 , BC Math 12, etc.) needed to take the associated exam to get credit for graduation. The local universities had all they needed to fairly compare applicants between schools, since the exam and school grades were shown separately on our transcripts. In addition to looking out for individual student outliers in terms of grade discrepancies, they could calculate a historical average difference between school and exam marks per subject per school and thus “adjust” school grades across the board for patterns of consistent bias if they wanted to. I actually know for a fact that competitive programs in Ontario (e.g. engineering at U of Waterloo) would make these adjustments for BC school applicants (they also would encourage everyone to take their national math contests then used those scores as well to further adjust).

This accountability through exams had positive downstream consequences. It really forced teachers to cover the full curriculum lest their students be put at a disadvantage. It also incentivized giving grades, especially in Grade 12, that would approximately align with what students would get on the exam. It was a highly effective restraint on grade inflation. Not only because it would look suspicious if your school grades were always so much higher than exam marks, but also as a defense against student or parent complaints that your grades were too low. This in turn meant that the universities could make admission decisions that were not holistic at all. It was quite uncommon, even at flagship universities, to be asked to write a personal essay, list extra-curricular activities or list any other accomplishments for admission to a regular undergraduate program. That was reserved for scholarships, some very competitive special programs or something that required a portfolio (e.g., fine arts program).

As for the new, stupid, grading rubric, you may be surprised to learn that it isn’t even new (the never-ending story in education reform)! While the old BC high school grade and exam system was laudatory, I can report that back in the early nineties at least some school districts (such as mine on the North Shore) were using a three level grading system on reports cards as late as Grade 7. The vague levels were “Proficient”, “Satisfactory” and “Needs Improvement”. A level would be marked for each skill in a standard list on the report. For example, you might see something like: “Multiplication and division - S”.

While okay for nursery or primary school, this system had serious problems in the older grades. In fact when my brother, who has small kids in the province, heard that they were introducing the Proficiency Scale you describe for K-9, his first reaction was horror that they were bringing back the old, bad system under which he had suffered (and now extending it to even later grades!) I hadn’t realized this, but apparently he attributes the fact that his middle school slacking and disengagement (then subsequent developing of gaps in some key areas) was unnoticed by our parents for years to the uninformative report cards. He is quite passionate about this. He feels it really affected his educational trajectory.

For me, I have a grudge against this resurrected proficiency scale of the opposite kind. I was a very good student and especially gifted at math. But this talent was unknown to my parents, and, to a certain extent, even to me, until I got to high school with proper percentage grades. When all you get is a bunch of “proficients” on everything, how is anyone to know if that means 1 in 5 good or 1 in a 1000? Combined with BC’s longstanding allergic reaction to talent identification or acceleration, me and many of my fellow British Columbians lost opportunities to go deeper and faster in our schooling where we could.