Straight Talk on Gifted Education for Mayor Mamdani – and Everyone Else

Getting rid of public gifted education programs will accelerate the enrollment crisis hitting American public schools

When Zohran Mamdani came out in favor of eliminating New York City’s gifted and talented program in the earliest grades, it represented the latest chapter in an ongoing debate about gifted and selective schooling options in our nation’s largest district.

One might have thought this was political suicide. Advanced academics are super-popular, as Josh Dwyer noted in his recent overview of public polls. Eliminating tracking was the sixth-least-popular Democrat policy in a recent review of national polls, scoring almost as low as “defund the police.” Going to the dentist is more popular than detracking.

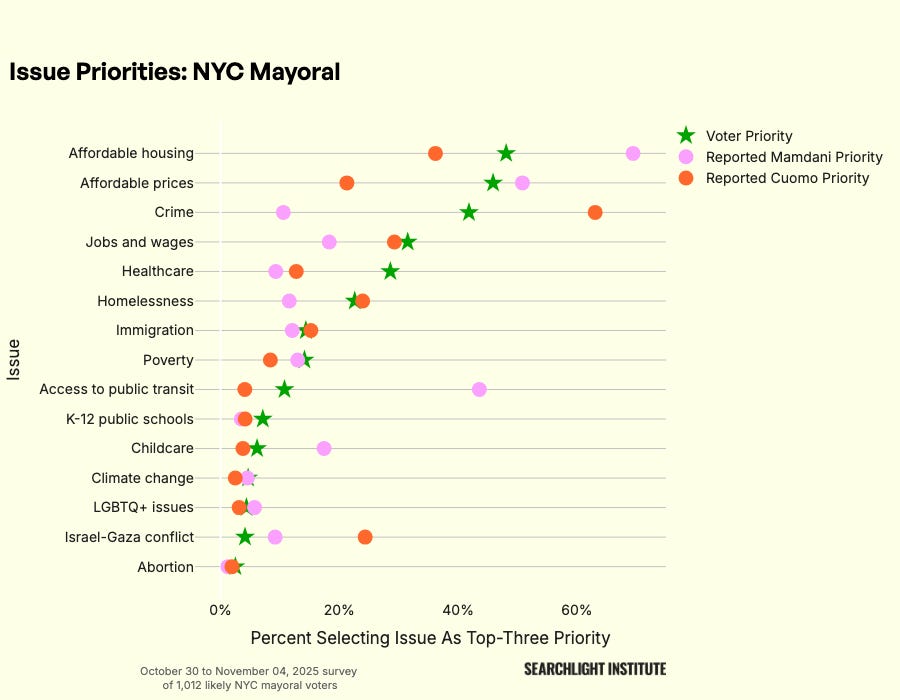

Still, Mamdani soared to victory — a reminder that education seldom ranks high in voter priorities. In the New York City election, education wasn’t a motivator:

Sadly, it’s rare for education to register much higher than this, even in local elections. New Jersey’s election gave us another example. Democrat Mikie Sherrill had an embarrassing gaffe around education policy, but still cruised into the governor’s seat. Education is such a middling issue that it doesn’t even make some Pew surveys.

To get leaders to take school quality seriously, we should probably focus less on caucusing and more on costs. Because declining school quality is hitting district bottom lines via enrollment declines.

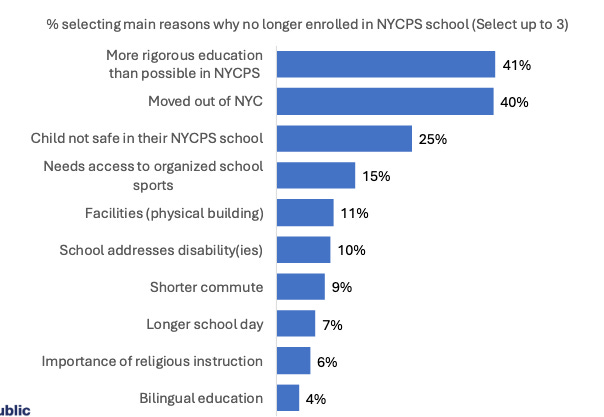

Let’s take New York City’s own data. The DOE recently conducted exit interviews with parents of disenrolled students, to understand their reasons for leaving. Remarkably, 41% responded that they wanted a “more rigorous education than possible in NYCPS”:

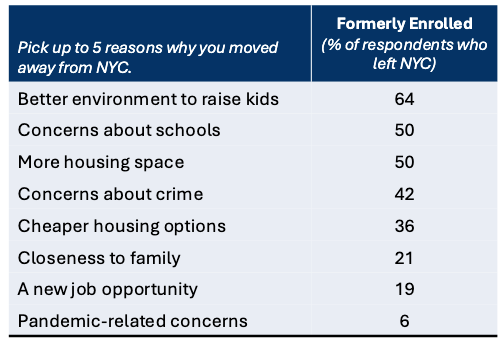

Of the families who “moved out of NYC,” many fled over academics: 82% said that school options drove the decision to leave “to a great extent.” Respondents were as likely to say they were leaving the city over “concerns about schools” as “more housing space” (which will hit home for anyone who has done time in NYC apartments).

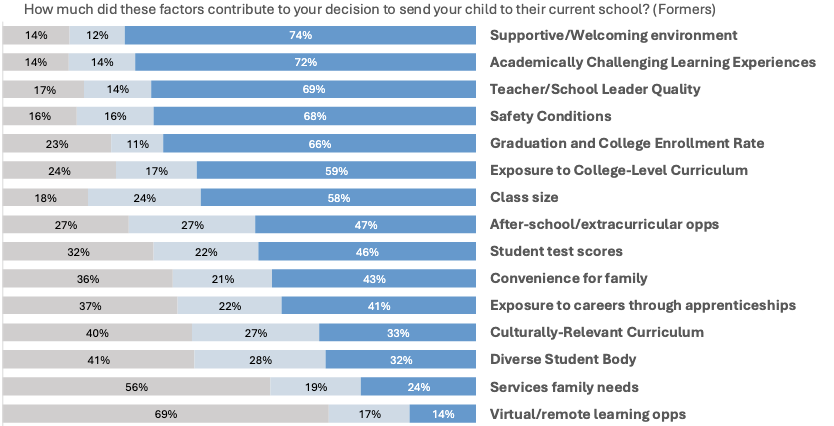

To disenrolling parents, “challenging learning environments” and college-level curriculum mattered in a way that diversity considerations simply did not:

The NYC disenrollment survey reflected a diverse group of parents, as you’d expect for New York City: 42% were Black or Hispanic and 8% were multi-racial. Only 23% of respondents were white. If Mamdani is shrinking gifted programs to appeal to diverse families, he’s missing their signals.

New York isn’t the only city losing parents over academic concerns. A Seattle Public Schools report found that the district was “disappearing” its top math students by dismantling its advanced courses. As the Seattle Times reported, families “who disenrolled their students from SPS overwhelmingly cited concerns about the quality of education and the curriculum as top reasons.” What’s more, a majority of local parents had considered disenrolling their children “over concerns about the quality of education.” Egads.

The Boston Globe reported on parents pulling kids out of Cambridge schools over math detracking. This is a national trend. And while we’re talking about trends...

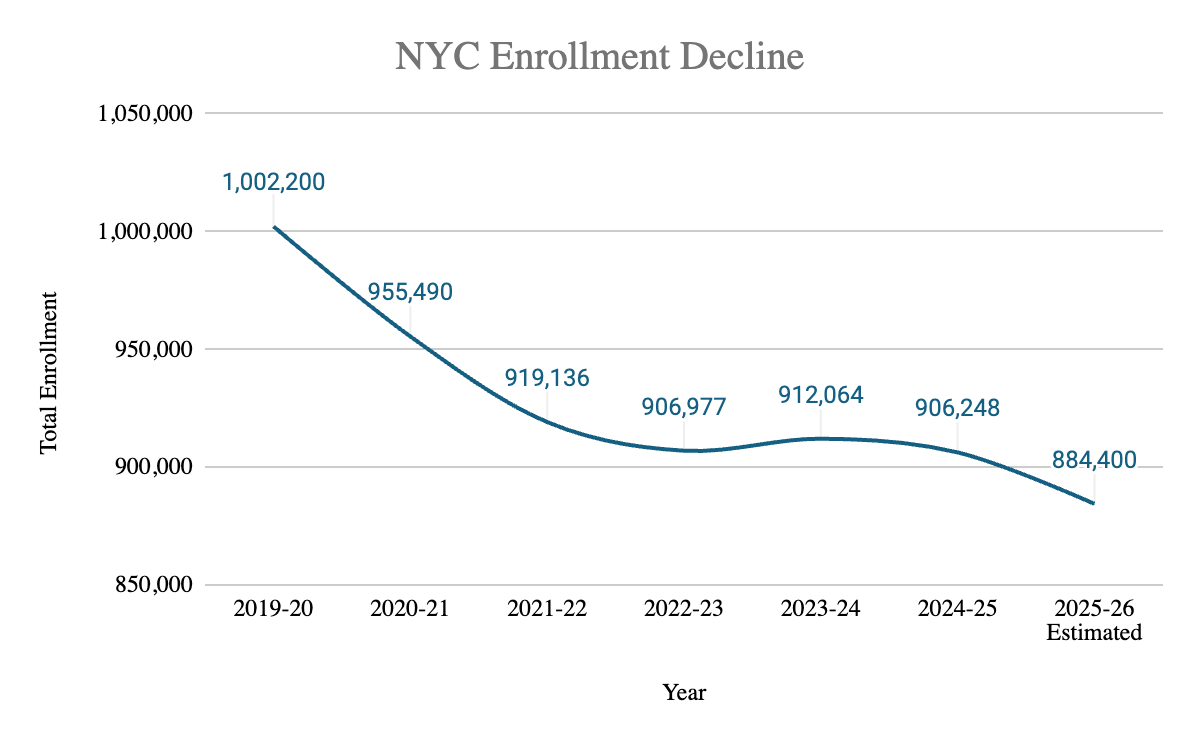

Enrollment declines are plaguing American schools, thanks to a combination of declining birth rates, pandemic losses, and access to vouchers. In some areas, it’s acute; San Diego expects to lose 28% of its students by 2044. School districts are hiring marketing firms to help them retain students. This issue is top-of-mind for every education leader in America right now.

New York City has already been gushing enrollment. The most recent figures are a major red flag for a district with more than a million students before the pandemic; enrollment is down 12% versus 2019-20:

So, my straight talk for Mamdani — and every other leader in America — is simple: you are begging to accelerate enrollment declines if you roll back advanced academic programs. Gifted programs may not drive decisions at the ballot box, but parents will vote with their feet over weak academics. School leaders can’t afford to ignore them, at a very practical, budgetary level.

I have straight talk for advocates of advanced academics, too: we can’t afford to narrow the tent by focusing only on high-flying students.

All parents have concerns about academic quality, not just parents of advanced learners. Conor Friedersdorf synthesized poll data and reported that parents’ number one goal was “making sure students have strong fundamental skills in reading, math, and science.” One recent poll illustrates the imbalance parents perceive in district priorities: “By a 32-point margin, participants said they would favor candidates who supported teaching less about race and more about core subjects like math and reading.”

I believe it will take a movement, likely led by parents, to demand stronger and more academically-focused schools. Michael Petrilli of the Fordham Institute just suggested the same: the forces of political populism may put the EdReform reins in parents’ hands. Movements need members, so we need to keep the tent broad.

Also, if you want more kids in advanced classes, you need to start ‘em young with strong foundations. Boston Public Schools offers a cautionary tale. The district voted to return to higher admission standards for its exam schools, yet leaders flagged a pipeline issue: “Less than 1,000 BPS sixth-graders meet or exceed state standards in English language arts and math.” One leader put a fine point on it: “We do not have the number of students in the entirety of Boston Public Schools performing at grade level in ELA and math to fill the total available seventh-grade seats across the three exam schools.” My heavens.

Kelsey Piper’s excellent article on detracking suggested automatic enrollment policies as a way to expand access to advanced courses. Jonathan Plucker has also taken up this cause. Yet those policies ultimately rely on students coming through schools with strong foundations in reading and math. The recent UCSD report on unprepared college freshmen makes clear that many students are not.

To be an advanced academic advocate is to be a core instruction advocate, however one looks at the issue.

It feels reasonable to demand protections for Gifted & Talented programs in New York City because the city is investing in foundations — and it’s working. The two year old NYC Reads initiative is showing promise:

“Reading test scores climbed seven points for New York City public school students who took state exams in the spring, a substantial increase over previous years that comes after efforts to change the way students learn to read… The improvement was especially large for third-grade students, a crucial benchmark because children who cannot read well by then are more likely to drop out of high school and live in poverty as adults. About 58 percent of third-graders showed proficiency in reading, a nearly 13-point rise from the year before.“

I’d like to see as many voices calling on Mandani to maintain — and invest further in — NYC Reads as those seeking to defend G&T.

Let’s pair calls for Algebra in 8th grade and gifted programs in elementary schools with demands for math foundations and knowledge-rich curriculum starting in kindergarten, for the good of American schools.

I live in Seattle and EHC types here don’t even consider Seattle Public Schools any more. You can’t fix that with marketing.

Yes, not good. But de Blasio had very similar ideas on education and he failed to follow through. In fact, creating universal pre-k was likely best thing he did. My guess is Mandami does not get this done either.