Polls Show that the Public Supports Gifted Education

So why do we have such lackluster policies?

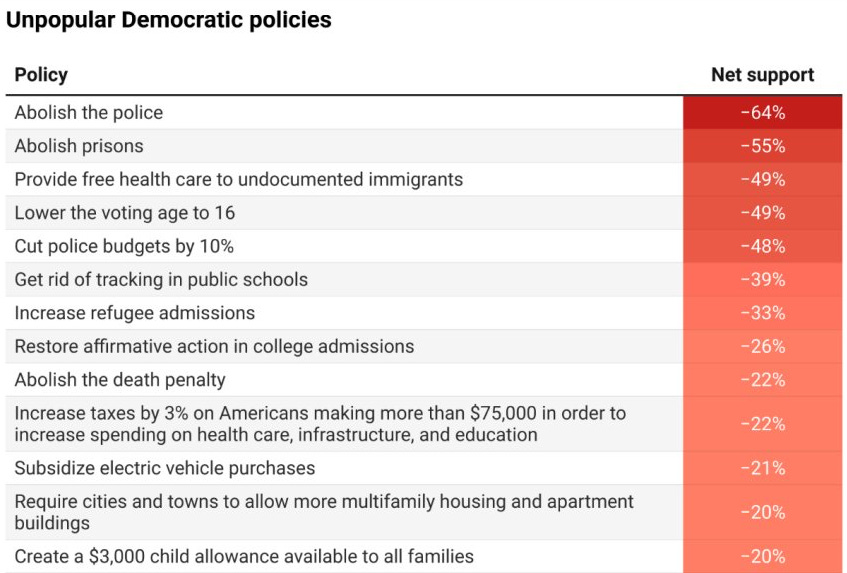

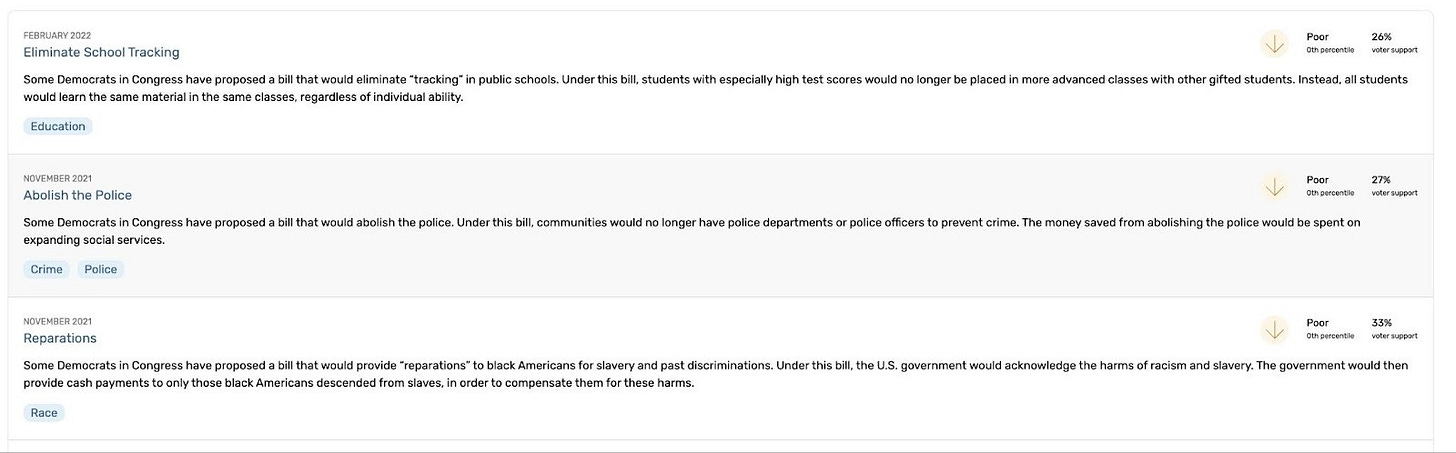

A new report from Welcome, the Democratic-aligned PAC, is dominating conversations on X this week. Titled “Deciding to Win”, it offers a roadmap for Democrats to rebound from 2024 by shedding unpopular progressive positions. Education isn’t the centerpiece, but one detail jumped out to advanced learning advocates (like me): Voters strongly oppose eliminating tracking (ability-grouping) in public schools, ranking it among the most toxic policies associated with Democrats.

This echoes findings from David Shor, Head of Data Science at Blue Rose Research, who has long flagged removing advanced classes as “literally the single most unpopular thing Democrats can talk about.”

When it comes to other issues in advanced education, like gifted and talented programs, a similar story arises from the data.

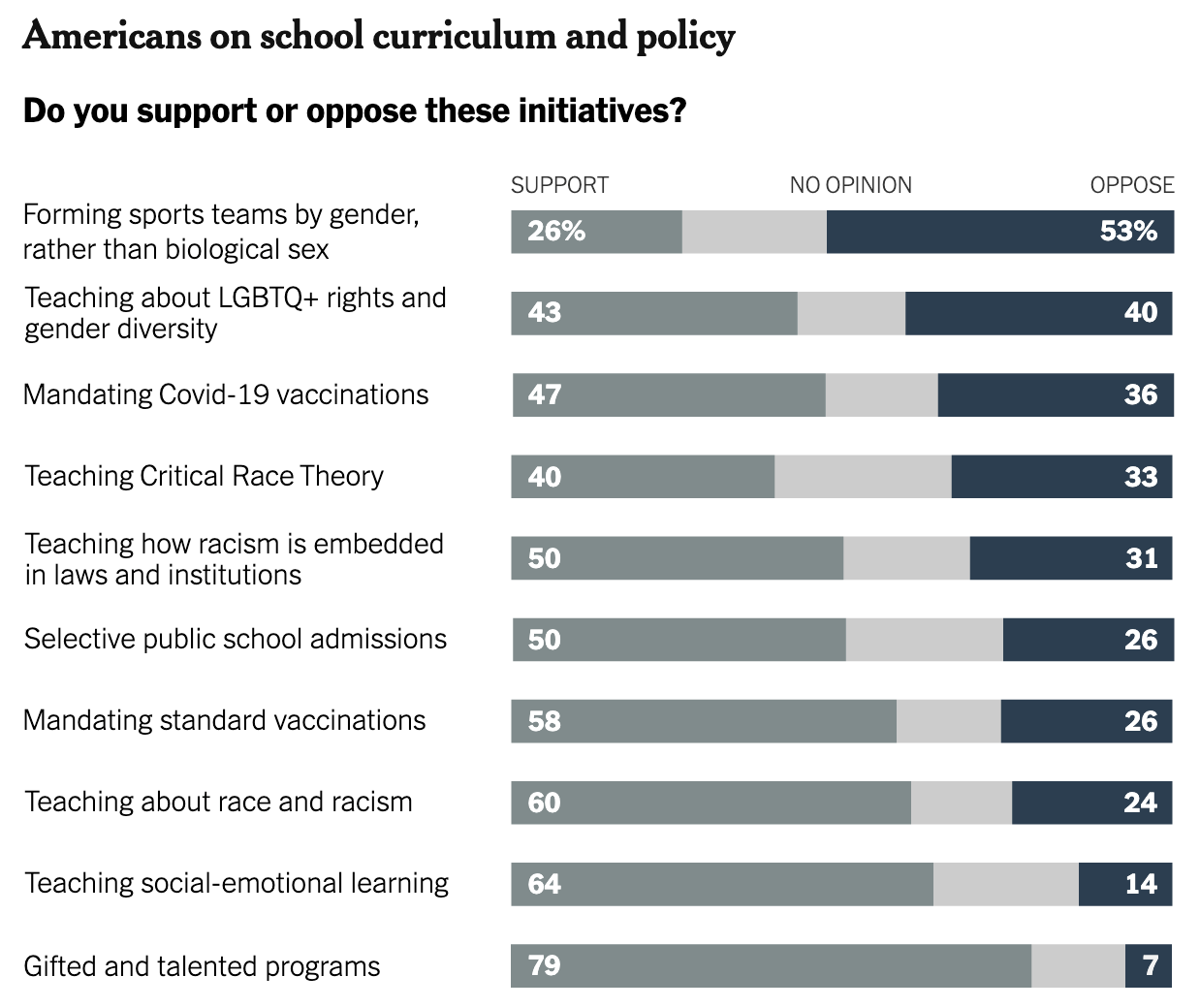

For example, a 2022 New York Times poll found that 79% of people support gifted and talented programs.

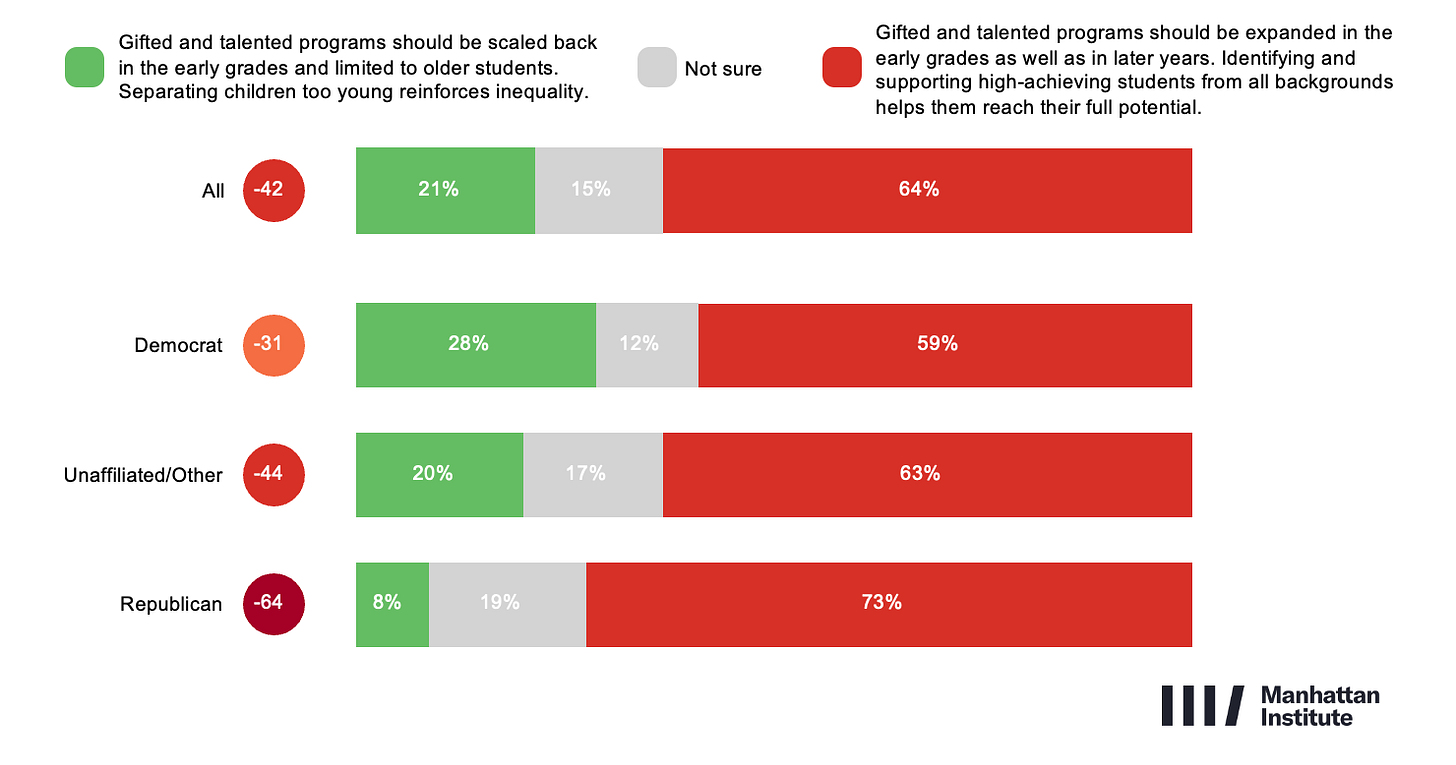

A more recent poll released on October 28 by the Manhattan Institute showed that a plurality of New York State and New York City voters believe that G&T programs should be expanded, not eliminated. This includes almost 60% of Democrats, nearly three-quarters of Republicans, and almost two-thirds of independents.

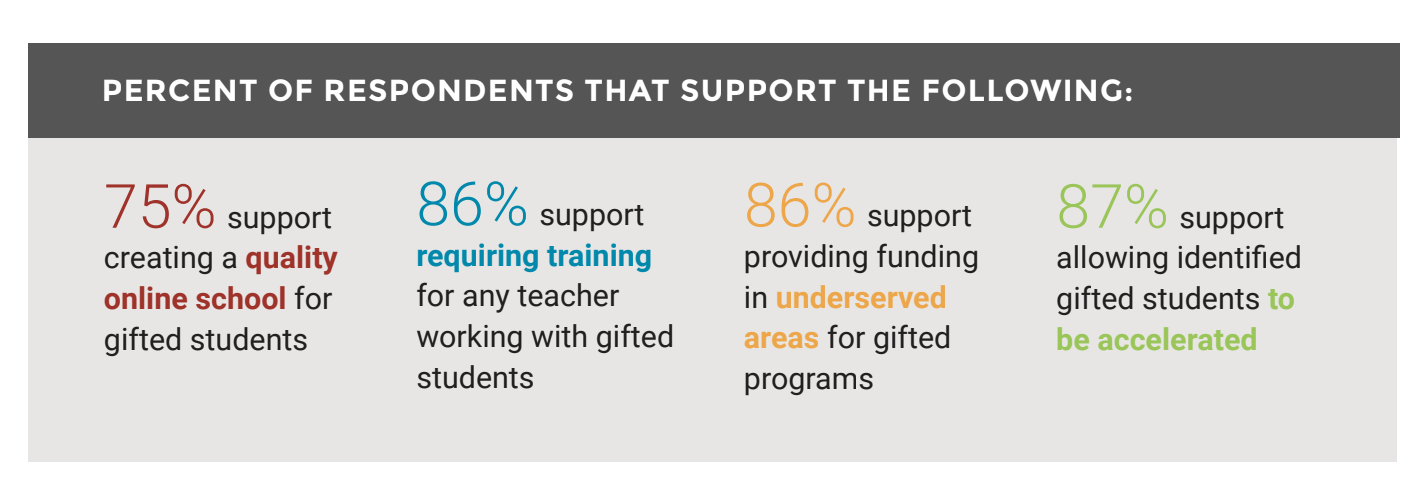

Additionally, a 2019 Institute for Education Advancement (IEA) survey revealed:

75% public support for creating an online school for gifted students.

86% public support for requiring teachers to have training in gifted education.

84% public support for funding gifted programs in underserved areas.

87% public support for acceleration.

Yet the policy landscape tells a different story. According to the National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC):

No federal mandate exists for gifted education.

The only federal funding that specifically supports gifted education is the Javits Grant, which was funded at $7 million in the FY2025 budget.

Only 28 states mandate that advanced programs exist for students who are identified as gifted, and just twenty-three set standards and guidelines for those programs.

Only 13 states have an acceleration policy.

Only 10 states have a policy addressing equity problems in their gifted programs.

Why the disconnect? Why doesn’t public support for gifted education translate into strong public policies that help advanced learners succeed?

The reason: the public believes schools are doing a good job when it comes to meeting the needs of advanced learners.

The same IEA survey mentioned earlier found respondents gave schools an A or B for serving advanced learners – significantly higher grades than they gave schools for serving other learners, including disabled students.

The conclusion of the report sums it up perfectly:

“The public seems unaware of the disparity in gifted education policies among states, or the inadequate levels of funding for gifted education nationwide. Making the general public fully aware of the current state of gifted education should become an integral part of gifted education advocacy.”

Here’s the good news: The public is aligned with advocates when it comes to advanced education. It opposes dismantling it and wants advanced learners to have access to an educational environment that will help them thrive.

The bad news: It lacks awareness of how little of it actually exists.

This gap — between public will and policy reality — remains the central challenge to advocates.

This is a challenge that the Center for Educational Progress is intent on solving.

We have an exciting announcement coming soon about our next steps. Stay tuned.

At this point my only hope for gifted and talented education is better AI tutors. In small schools/school disctricts there is no way that our existing schools can provide tracked education for the gifted students - who do not constitute a single homogeneous body. This is true, even if the school truly wanted to support such students, which is generally not the case. Thie dispersin in student subject mastery is particularily severe in subjects that are sequential, as the students are going to progress at different rates and the dispersion in accomplishment is going to be very large. We already have 4th and 5th graders with 12th grade reading levels, and 12th graders with 3rd and 4th grade reading levels. Math is subject to great dispersion, since it is cumulative. It is not hard to have 14 and 15 year olds doing college calculus while some of their peers have issues with simple arithmetic. Teachers can not accomodate too great a variation in mastery in a class - and smarter students learn and progress faster.

Just a note - while standardized tests have their limitations, they are the best instrument we have at this point - at least for classical academic skills. Frankly, you could probably supplement the standardized tests with any of the strongly g-loaded intelligence/aptitude tests. Artistic talents require a different measure.

We should disentangle G&T from advanced coursework. They were never intended for the bright kids who are good at school and the training and prep for gifted education emphasizes that gifted kids are 5-6% of the population and they are characterized by their failure to succeed in school despite being otherwise intelligent. So your kid who has great grades and who would benefit from harder materials or a faster pace is *not* gifted. It’s the disengaged kid in the basic course scraping by one point above failure but who goes home and codes his own video game or writes poetry. They’re creative misfits who struggle socially and bristle at structured learning. That’s why so much gifted curriculum is behavioral, not academic. Indeed, it’s common for gifted kids to go more slowly but deeply on content.

If you want advanced coursework, then make advanced coursework available. Don’t shoehorn it into programming that was never meant for the top academic performers anyway.