Research Finds Persistent Inequalities in Algebra Placement

But universal student screening and automatic course enrollment can help

Editor’s Note: This post is part of a new series highlighting research that offers meaningful and thought-provoking contributions to the broader public discussion of how student learning needs are not being met, and how we can solve such issues. We consider the work valuable and worthy of careful consideration, but the interpretations and conclusions presented here should not be understood as the official positions or endorsements of this organization.

Dr. Daniel Long is a Senior Research Scientist at NWEA, and one of the authors of a new report, “Unequal Access to 8th-Grade Algebra: How School Offerings and Placement Practices Limit Opportunity,” which you can find here.

We look forward to reading future research from Daniel and the NWEA!

“Algebra in eighth grade” isn’t just another math class; it’s a key gateway. Students who take Algebra early are more likely to succeed in advanced high school math, pursue STEM majors in college, and earn more over their lifetimes. However, these benefits of early Algebra are not equally available to all high-achieving students.

New NWEA research finds persistent inequalities in access to and placement in 8th-grade Algebra classes. This brief draws on recent NWEA data from 162,000 eighth-graders across 22 states to show that access to 8th-grade Algebra1 remains highly inequitable. Fewer than half of high-poverty and majority-black and Latino schools offer Algebra in eighth grade, closing off access to advanced math pathways for students in those schools. And even among high-achieving students in schools that do offer Algebra, black students are systematically less likely to be placed in it. Placement practices — and not ability — are often a key driver of these inequities. Policies like universal screening, however, can help.

Who gets placed in Algebra when it’s available

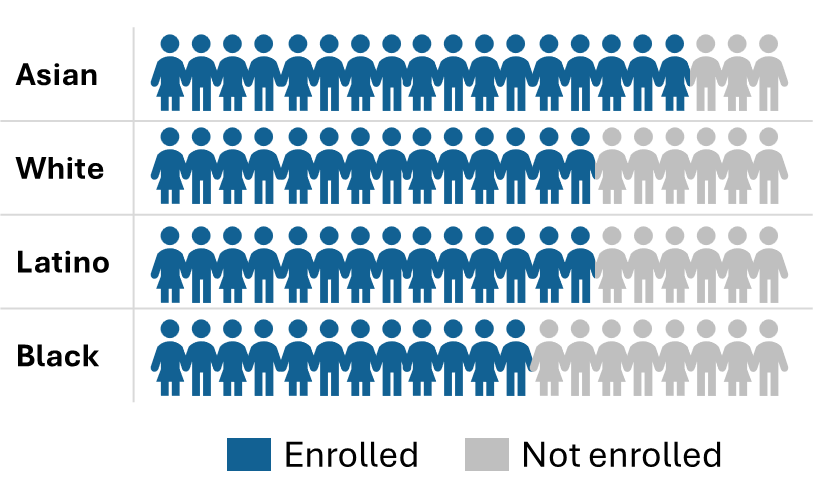

In schools that do offer Algebra courses, enrollment isn’t equitable. More than half of Asian students enrolled when the course was available, compared to just 22% of Latino students and 17% of black students. These gaps show that availability alone doesn’t guarantee access where appropriate. For many students, especially black and Latino ones, the barrier is not whether their school offers Algebra, but whether they are given the chance to take it.

Among high-achieving students, the enrollment gaps cannot be explained by differences in academic preparation across student groups. The inequities persist even when we limit the analysis to just the highest-achieving 20% of 5th-graders. Among top-quintile students, 84% of Asian students and 68% of white and Latino students were enrolled in Algebra, compared to only 60% of black students. In other words, high-achieving Asian students are likely to enrolled in 8th-grade Algebra at more than 1.4 times the rate of similarly prepared black students.

Figure 1: Among top-quintile students, black students are the least likely to be enrolled in Algebra

Note: Each box shows a group of 20 students of each racial/ethnic group. The blue figures show 8th-grade students enrolled in Algebra in schools that offer 8th-grade Algebra. The grey figures show the group of students within each racial/ethnic group denied access.

These disparities within the top of the achievement distribution suggest that ability isn’t the barrier for high-achieving students; placement practices are. When high-achieving black students have lower access to advanced math opportunities, schools effectively close doors to future STEM opportunities.

Placement practices matter

The persistence of access gaps even among well-prepared students points to a clear explanation: the way schools make placement decisions. When Algebra access depends on subjective or inconsistent criteria, even students who are ready for advanced math can be left out.

Most schools use a mix of standardized test scores, teacher recommendations, and parent requests to decide who gets placed in Algebra. While these methods may seem fair on the surface, research shows they can introduce bias. For instance, teachers have rated white students as higher achieving than black and Latino students, even when test scores are similar. Parent referrals are also more common among white and affluent families, which can widen gaps in access. Together, these practices reinforce existing inequities rather than expand opportunity for all.

Universal screening can prevent otherwise qualified students from being left out

One promising approach to reduce bias in placement decisions is to use universal screening and automatically enroll high-achieving students into advanced math pathways. This approach ensures that placement decisions are based on readiness, not on referrals or resources.

Universal screening is not only a fairer approach, but a more efficient one as well. It reduces the administrative burdens of subjective placement decisions, saves staff time, and ensures more students get the opportunities they deserve.

Several states — including Colorado, Nevada, North Carolina, Texas, and Washington — have made progress in identifying and supporting high-potential students from low-income and minority backgrounds through universal screening.

North Carolina implemented an automatic enrollment policy that placed top-scoring students from state math tests into advanced math classes for grades 3 and higher. These policies have reduced the misalignment of high-scoring students from 10% to 3%. These policies have also increased the percentage of high-achieving black students enrolled in advanced math. For example, the rate of black students enrolled in advanced math increased from 88% to 92% between the 2022–2023 and 2023–2024 school years.

Texas also has seen increased equity in Algebra placement through universal screening and automatic enrollment. In central Texas, from 2014 to 2021, the percentage of high-achieving black students taking 8th-grade Algebra rose from 40% to 70%, and for high-achieving Latino students, from 50% to 70%. Recognizing the success of these initiatives, Texas passed a law in 2023 requiring that students who score in the top 40% statewide in fifth grade receive advanced math instruction to prepare for Algebra in eighth grade.

In total, these efforts help ensure that students who show strong academic potential are not overlooked.

What policymakers and education leaders can do to expand Algebra access

Closing Algebra access gaps requires action at both the state and local levels.

Policymakers can work to advance all qualified students by supporting state-level universal screening policies and policies to expand Algebra course offerings, especially in rural and high-poverty schools. This may require additional resources for hiring qualified math teachers, as well as providing professional development.

School and district leaders can improve placement practices by adopting universal screening to identify students ready for advanced coursework that might have otherwise been overlooked. In addition, expanding targeted academic supports, such as increased tutoring or double-dose instruction, can help more students build the key skills needed to succeed in Algebra. Research shows that targeted instruction on these foundational skills can dramatically improve students’ ability to learn new Algebra content.

Our analyses focused on whether schools offered Algebra or higher in 8th grade. A school that had any 8th grade courses flagged as Algebra 1, Algebra 2, Geometry, Calculus, or pre-Calculus were considered to have offered 8th-grade Algebra.

Screen everybody - some students may be misidentified. And offer Algebra 1 before 8th grade for those students ready for it. It is not a difficult subject and many younger students are ready for it.

You wrote: “For example, the rate of Black students enrolled in advanced math increased from 88% to 92% between the 2022–2023 and 2023–2024 school years.” The wording here is off, and a few other points need correcting.

North Carolina first passed a law saying any student who scored at the highest level on state tests in grades 3–12 would be automatically placed in the most rigorous math course. Elementary schools pushed back because only students officially labeled Academically Gifted could enroll in enriched math, even when other top scorers were just as capable. The law was then adjusted to start at grade 6. Teachers can recommend students as well, and about half of the students who take Algebra I in eighth grade are there because of a teacher recommendation. We don’t know whether minority students with the same scores receive the same rate of recommendations. The accountability system only reports the percentage of level-5 scorers who were placed in the most advanced option.

When the reporting requirement started in 2018–19, the state also changed the cut scores so that far fewer students earned the top level. As a result, high school report cards show that no one did, because the number of top scorers is too small to report. Middle schools don’t report it at all.

So that “88% to 92%” figure refers only to Black students who scored at the top level and then were placed in advanced math. It doesn’t mean 92% of all Black students. And we can’t tell whether this is better or worse than before because the reports don’t include that history.

We also can’t tell whether eighth-grade Algebra I still functions as a gateway. Its importance used to come from the fact that students who took it were the ones who moved into honors math in high school. We don’t know whether enrollment in advanced high school math has gone up, down, or stayed the same, because that isn’t being reported.