Hobson v. Hansen and the Decline of D.C. Schools

A story of institutions

Editor’s Note: I will take a seven-month leave of absence from the Center for Educational Progress and from my online writing starting tomorrow. Please enjoy this account of the investigation that consumed much of my summer. There is more to be said about some of the details, but I wanted to release it in some form before I disappear. Be well while I’m away.

In Washington, D.C.’s history, there were three superlative predominantly black public schools. Two of them were destroyed, one by negligence, one by malice. The third was almost stillborn, strangled in its infancy and neglected in its adolescence, but it persisted.

The first, Dunbar High School, stands out as the crown jewel. From 1870 to 1955, it was Washington, D.C.’s only academic high school for black students—the first and best public black high school in the nation. Its alumni include Charles R. Drew, a prominent surgeon and researcher; William H. Hastie, the first black federal judge; Charles Hamilton Houston, who was dean of Howard University Law School and NAACP first special counsel; and many other black leaders of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A school still bears its name, but it is not the school it once was.

The second, Amidon Elementary School, was built in 1960 as part of an urban renewal project. At the peak of the city’s white flight, it was one of the only schools in the city to maintain a truly integrated student population over several years. It used phonics to teach reading and focused on basic skills, against the popular guidance in education schools of its day. It lasted seven years before being dismantled—not because it failed, but because it worked. The people who dismantled it won a Medal of Achievement at the National Laboratory for the Advancement of Education for their trouble. It has since been almost forgotten to history.

The third, Benjamin Banneker High School, was the subject of a bitter fight, multiple failed votes, and the resignation of arguably the district’s best superintendent in modern history before the school board allowed its creation in 1980. For more than a decade afterwards, the board looked at it with suspicion and starved it of funding, including denying it readily available federal funds. It now ranks consistently among the best high schools in the country.

What follows is the story of those schools and the men and women who fought over them. It stems from a question I couldn’t shake during my study of education law: Why is the only reference to ability grouping in my casebook a 60-year-old court case the book advertises as likely no longer being good law?1

I assumed, when I started my research into Hobson v. Hansen, that 1967 case on ability grouping in Washington, D.C. schools, that I would find a grim contrast to today, with bigots using tracking as a pretext to keep black students down. What I found instead is a story that cuts right to the heart of every education fight and many public policy fights of the past three generations, a tragic years-long wrestle between two remarkable men and their competing visions for what education ought to be, and the quiet catastrophe in its aftermath.

This is the story of Julius Hobson, Dr. Carl Hansen, and the world their conflict built.

Into the Segregated City: 1907-1947

Carl Hansen was already an experienced hand in education when he got a 1947 letter from the Washington, D.C. superintendent of schools inviting him to accept a position as the superintendent’s executive assistant. He had spent twenty years as an educator in Omaha, Nebraska, first as a teacher, then as the principal of an integrated technical high school. His Omaha superintendent warned him against the position: “Nobody ever succeeds in that school system. He merely holds on until he gets fired or retires.” But Hansen, only a few years out of a venture out to the West Coast to get a doctorate from Southern California University, was ready for another adventure. He accepted the job, packed up with his wife and two young children, and headed east.2

The Washington school system he was headed for was very different from the Omaha system he left: a southern school system, strictly segregated since its creation and managed not by the local city but by a school board appointed by the federal judges (part-time non-specialist volunteers, in charge of setting the overall direction for the school system), a board-appointed superintendent (in charge of carrying out the day-to-day operations of the district in line with the board’s directions), and Congress itself (in charge of funding and apportionment). All clashed repeatedly over questions of control and direction. Since 1906, the Board had been mandated by law to contain a mix of six men and three women; by tradition from that point forward, two of the men and one of the women were black. The superintendent position was usually stable, with Hobart Corning—the superintendent when Dr. Hansen joined—serving for twelve years from 1946 to 1958 and his longest-serving predecessor Frank Ballou serving from 1920 through his retirement in 1943.3

Under Ballou, the district’s segregation was total and its reputation poor. Every administrative position needed duplication between the white schools and the black schools, with coordination and communication strongly discouraged. In 1938, Ballou reprimanded a white administrator for getting lunch with his black counterpart. When famous singer Marian Anderson wanted to give a concert in the auditorium of the district’s Central High School, the Board and superintendent denied the request, drawing intense local and national anger. Anderson went on to instead present a free concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.4

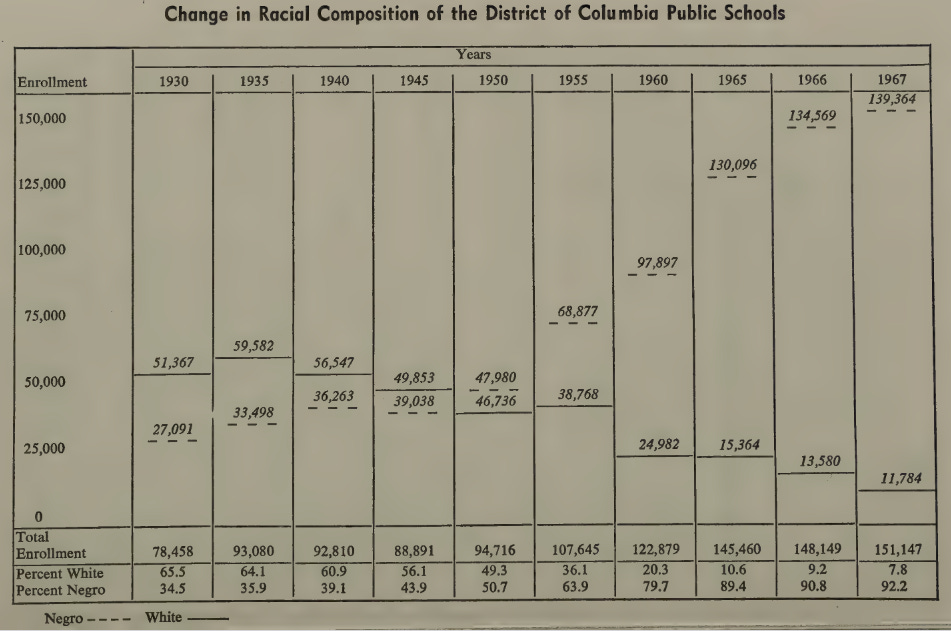

The District’s population was transforming by the time Hansen arrived. Its white enrollment had peaked at 59,500 in 1935, when the system had only 33,500 black students. By 1945, the white student population had declined to 50,000, while the black population had grown to 39,000. This led to repeated tensions in the system, particularly around assignment to schools: as white student populations shrunk and black populations grew, administrators would periodically close white schools and reopen them as black schools, as white students protested the loss of their schools while the black community protested the receipt of white hand-me-downs.5 By 1947, 45 percent of the district’s population was black, and 72 percent of its construction budget was going towards black schools, with numbers only increasing from there.6

Serious efforts at education research were well underway in the early 1900s, and ability grouping was a topic of persistent fascination. Meta-analyses of the 1920s and 1930s noted uncertainty, emphasizing that grouping without curricular changes to match seemed to be ineffective, but grouping that adapted curricula to the pace of students could be promising. “Homogeneous classification,” a 1930 analysis of several studies noted, “may be effective if accompanied by proper adaptation in methods and materials.”7

A few years later, the psychologist Ethel L. Cornell cut through the mess. She noted in 1936 that two competing schools of thought had been in conflict in education since the earliest attempts to study it, and that the conflict was evident both in studies and in theory. One theory held that “a democratic education should offer the same content to all.” The other, that “education cannot be democratic unless it varies the educational pattern, the content, and the goal, as well as the speed and the method,” to fit pupils’ varying needs. In the first, people treated ability grouping simply as a refinement of grading, while in the second, people saw it as cutting across and supplanting the traditional grade system. Cornell noted that its results depended less on the fact of grouping, more on its philosophy, its accuracy, and willingness to differentiate content, and that both objective and subjective results favored grouping with adaptations.8

Against this backdrop, the white and black schools tended to use various schemes to group students by ability. Most notable within the black system was its decision to run a single academic high school, Dunbar High, for the most academically driven black students from around the District, while sorting those who were less academically inclined into one of the District’s two other black high schools. The decision bore fruit, with the school drawing a highly educated faculty, preparing generations of black leaders, and standing as a national model for black excellence.

Into this system came Hansen, a committed liberal institutionalist who believed in the public schools as America’s most important social institution, a “traditional” educator at a time when traditionalism was already out of fashion, an integrationist and believer in colorblindness in a segregated world. Hansen believed that professional educators should be firmly in charge of schools with outside forces staying out. He championed basic, skills-focused education, ability grouping, and phonics for reading—something he noted had fallen out of favor in the 1920s as having become too highly technical and an end in itself before “revolutionists” rejected it instead of reforming it. When he was later made director of elementary schools, he immediately set about bringing phonics to the white schools that scorned it.9

The Foundations for Desegregation: 1947-1954

Upon arrival, Hansen began to lay a foundation for hoped-for integration in a careful, measured way. He focused on avoiding public controversy, aiming to push against segregatory practices “in such a manner that the Board of Education would not be forced to make an adverse ruling on what had been done,” believing that public controversy would set progress back. This included asking for approval before arranging a meeting between PTAs at a black and a white public school to handle a 1952 disciplinary incident.10

Public controversy came regardless: in 1949, when the Board and Superintendent rejected a proposal for a city-wide championship basketball game between the white and black division champions; in 1950, when an integrated pageant to commemorate the Capital’s 150th year came to white Anacostia high school, which cancelled the presentation; in 1952, when Superintendent Hobart rebuked Hansen for saying the system was “fast approaching practical integration on the administrative and teaching level.”11

One of Hansen’s first assignments was to set up a committee to develop a handbook on intercultural education, warning collaborators he couldn’t guarantee it would move the system closer to integration and that it was only focused on helping people “get along better together within the framework of total separation by race.” Much of the top school staff looked at with some suspicion, one noting that the word “workshop” had “a communist ring to it.” One segregationist Congressman threatened a reduction in appropriations as a result.12

At times, Hansen even acted as agent of the segregatory system, as when he stood in a white elementary school’s classroom doorway to block a black reverend from performing a sit-in on behalf of his son. In his memoir, he quoted the reverend’s commentary on the event approvingly: “I feel most strongly that it is undemocratic, unfair, and un-American to deny my son or any other American citizen a right to attend the nearest public school to his residence.”13

The inequalities within the segregated system were clear. The 1949 Strayer report, a survey of District schools authorized by the Senate and House district subcommittees, found sweeping problems and inequalities in the system. Black high school teachers taught more hours, black schools had older buildings, and black classes had more pupils than their white counterparts. The Strayer report noted “unnecessary and illogical” redundancies—two separate research and testing departments, two separate Boards of Examiners for applicants for teacher licenses. The district invested $240 in the instruction of each white student and $168 for each black student in 1953, the last year of segregation. Even though by 1953 black elementary students outnumbered white students 31,000 to 21,500, white schools had more than twice as many special education teachers as black ones. “Segregation,” an assistant superintendent in the district, Francis A. Gregory noted, “was a harmful luxury. It hurt not only those who were denied, but also those who were privileged.”14

Finally, in 1954, the minister and the many others who fought for racial integration won their victory in Brown v. Board of Education and in Washington, D.C.’s parallel decision Bolling v. Sharpe. By that time, the school system’s strict segregation stood in contrast to a gradual tide of desegregation in D.C.: desegregation of picnic areas, playgrounds, and swimming pools between 1941 and 1953,, desegregation of YWCA food services in 1944, merit-based federal appointments in 1948, a trickle of professional associations accepting black members through the ‘40s and ‘50s.15 Bolling turned the trickle into a flood: de jure segregation in the city was to end.

When the decision came down, unlike in most southern cities, the mandate was clear: President Eisenhower wanted the D.C. school system to become the model of integration in education, the nation’s eyes were on the District, and the administration would desegregate rapidly and without administrative resistance. On May 25, 1954, eight days after the Court’s ruling, the Washington Board of Education adopted a new racial policy: Appointments and promotions would be colorblind and merit-based. No pupil would be favored or discriminated against by race. Students were to attend neighborhood schools. No record would be kept of student or employee race.

Hansen’s time had come.

Miracle of Social Adjustment: 1954-1962

“The question is made about the educational level of children. That has been an administrative detail since we have had public schools. They give tests to grade children so what do we think is the solution? Simple. Put the dumb colored children in with the dumb white children, and put the smart colored children with the smart white children—that is no problem.” — Thurgood Marshall, Brown v. Board of Education oral arguments16

In what became known as the Corning Plan, the D.C. school district made several decisions: All schools would be desegregated as quickly and completely as possible, each one with new boundaries and the option for students to stay in their currently enrolled schools, school personnel would be appointed and promoted on the basis of merit, and the transition would be accomplished by natural and orderly means. (Miracle 45-46). In September 1954, D.C. students walked into integrated schools for the first time, with a smooth and uneventful first day.17

Opponents of desegregation sprung into action soon enough, with court petitions, protests, and encouragement of student strikes.18 Students at formerly white Anacostia High School staged a mass boycott lasting a week, ending only when the Superintendent ordered them to return or lose all honors and eligibility for extracurricular activities.19

Not every student wound up in a racially integrated school—many neighborhoods remained de facto segregated, such that 33,000 out of 41,000 white students were attending schools with some black classmates, while only 41,000 of 64,000 black students attended schools with some white classmates. Even as late as 1963, four all-white schools and 23 all-black schools remained.20

The clearest tragedy during the early desegregation process was the administration’s decision to turn Dunbar High School, like the rest of the newly integrated high schools, into a local neighborhood school instead of the magnet school it had been. Dunbar teachers faced an uptick in learning and disciplinary problems in their classes, dwindling enrollments in advanced classes and a newfound need for remedial ones. As the Board debated its 1954 plan, it did not spare a thought for what would happen to Dunbar. The idea of preserving some of what made the school special went unmentioned and unconsidered, and so the school went from producing the highest number of black PhDs of any school in the country to being just another neighborhood school.21

Hansen, meanwhile, was placed in charge of high schools instead of elementary schools after desegregation. 1955 was the first year white and black students had been tested using a common system, and Hansen saw the results as indicating an urgent need to adjust curricula. Nearly one-fourth of the District’s tenth graders were reading at or below a sixth grade level. In arithmetic, nearly half were at or below that level.

This observation led to Hansen’s first foray onto the public stage around the desegregation process—an exchange during an investigation into D.C. schools led by segregationist Congressman James C. Davis of Georgia. Over nine days of hearings, as Hansen put it, those conducting the investigation staged “an open gossip session in which all the neighborhood scandal was gleefully discussed.”22

In response to Congressional committees proposing a reduction in high school teaching positions, Hansen—hoping to stir the community and Congress towards more staffing and funding—released school test scores to local papers, advocating for upward equalization via additional funding. Thinking he might be opposed to integration because of his concern about lagging student academic performance, the Davis Committee called him to the stand. There, he expressed the view that the insularity of the segregated system had prevented sharing between the white and black teachers and had kept white teachers unaware of the academic performance of black students, isolating them and robbing them of the chance to learn as much as they could. When asked if he thought integration had carried on smoothly, he replied that it had been a “miracle of social adjustment.”23

As a result of this, the Anti-Defamation League encouraged him to write a pamphlet, Miracle of Social Adjustment, detailing the history of desegregation in Washington, D.C. He did so, pushing against negative stereotypes of black students and advocating for a sort of colorblind universalism. At the end of the pamphlet, he explained the one “big problem” he saw: many black students, facing environmental deprivation in the segregated inner city, lack the experience of other students and face unique challenges in learning.24

His solution, as he explained it, was focused on his “primary objective:” “the maximum development of every pupil, regardless of race, creed, cultural and economic status, and supposed capacity for learning.” To aid in this objective, he advocated for an increase in homogeneous grouping—what he called the “four-track plan” in high school—alongside a reemphasis on skills programs and subject matter standards, an increase in special education, the reduction of class sizes, and a building program to improve classroom facilities. “The prevailing spirit in the District of Columbia,” he said, “is positive and dynamic. It looks forward to a growing and improving school system, to a betterment of educational opportunities for all children, and is resolved to let no transient troubles prevent the realization of the ultimate goal, a better community through brotherhood.”25

Neither this nor his subsequent tour of Southern cities to give pro-integration speeches endeared him to Southern segregationists.

What was Hansen’s “four-track plan” for high schools? An honors curriculum for top performers, general and regular college preparatory curricula for the bulk of students, and a basic curriculum with smaller class sizes for tenth graders at or below sixth grade reading levels on tests. He envisioned flexible tracks with students encouraged to take the hardest classes they were prepared for.26

From Hansen’s angle, comprehensive high schools aiming to take in almost all high-school-age children were a new and positive development, but each student needed to be placed in classes where they were required to stretch and be met at their level. As he saw it, any public school system aiming to give every child at least twelve years of education faced a need of serious differentiation.27 This meant a certain degree of educational pragmatism: he wanted hard-to-teach students to remain in high school through the full twelve years, no matter the level they ended up at. “Teachers and citizens in general,” he wrote, “had better get a clearer picture of the concept of universal high school education. They are going to have to accept pupils where they are and help them to grow from that point. Their tight grip on the idea that high school is a sacred place to which tickets of admission are necessary needs to be loosened.”28

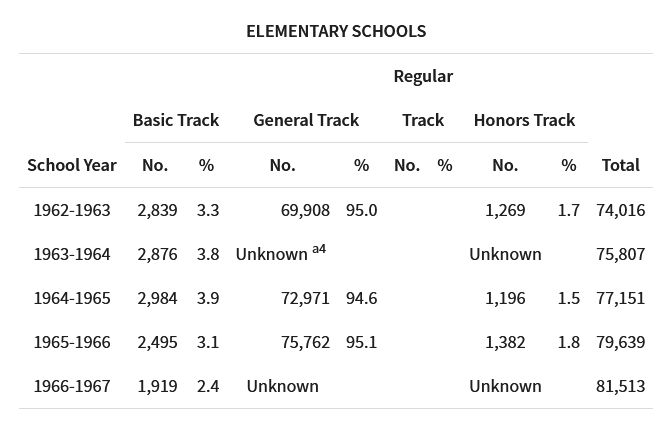

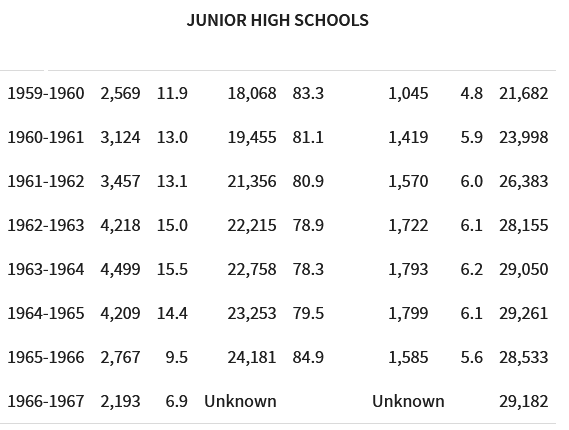

When he was promoted to Superintendent in 1958, he introduced honors and basic programs to junior highs and in the latter half of elementary schools as well. These were much smaller-scale than the high school program: in practice, some 2-4% of elementary students were in the basic track and another 2% in the honors track, with the numbers going up to 7-15 percent and 5-6 percent respectively by junior high.29

For a while, this all worked pretty well. Test scores rose consistently for black and white students alike in D.C. schools between 1955, the year the District’s independent testing systems properly merged and students were evaluated together for the first time, and 1962.30

Ability grouping remained an object of heated discussion, but Hansen’s position was hardly outside the mainstream. Education theorist John Goodlad summarized the research in 1960, calling it “perhaps the most controversial issue of classroom organization in recent years” and echoing the research problems and conclusions noted by Cornell and others decades earlier. He concluded that “the evidence, of limited value as indicated above, slightly favors ability grouping in regard to academic achievement, with dull children seeming to profit more than bright children in this regard. The advantage to bright children comes when they are encouraged to cover the usual program at a more rapid rate.”31

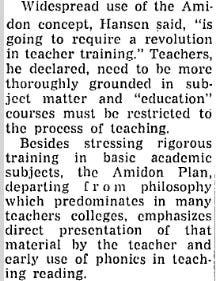

In 1960, Hansen saw the opportunity to put his elementary school ideals into action with the construction of a new school at the heart of a Southwest Washington urban development project. The Amidon School was to be his “put-up or shut-up operation,” a magnet school that would implement his ideal elementary school approach while inviting applications from around D.C. The focus of the Amidon was on teacher-directed, subject-matter-oriented instruction with demanding content, direct instruction, and difficult materials introduced early. Its reading instruction started young and kept phonics as its core, against the prevailing philosophy of education schools of its day.32 If his ideas fail when put to use, he said, he would abandon them. If they were effective, his staff would be willing to implement them more broadly.33

Hansen announced the program and began accepting applications from parents in March of 1960. The school’s student population was drawn partially from around the city and partially from the new and expensive development around it, but also took around 40 percent of its students from public housing in its local area. Throughout its lifespan, the school kept an enrollment of around 70 percent black students and maintained a racially integrated staff.34

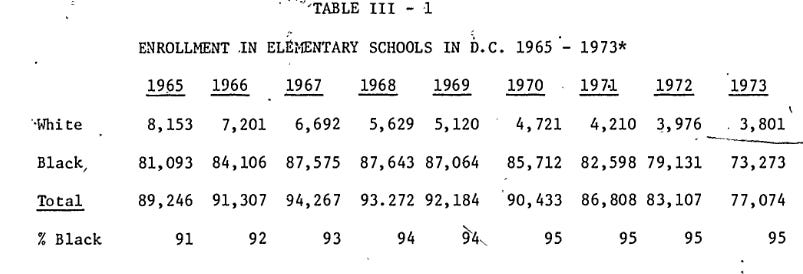

During this timeframe, the greatest complication the administration faced was the rapidly shifting racial composition and rapidly growing population within the city and its schools. While the city’s white population had been declining since 1935 and its black population growing throughout, by the 1950s, the influx of black migrants from Southern farms became a flood as the District’s white population dwindled. The year-over-year changes are stunning: the District schools went from being majority white in 1945 to 50-50 in 1950, up to 64 percent black in 1955 and finally 80 percent in 1960.35

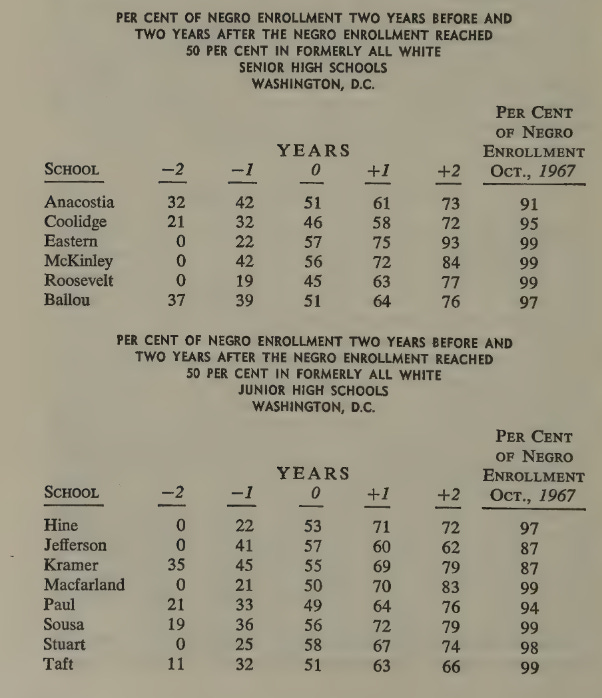

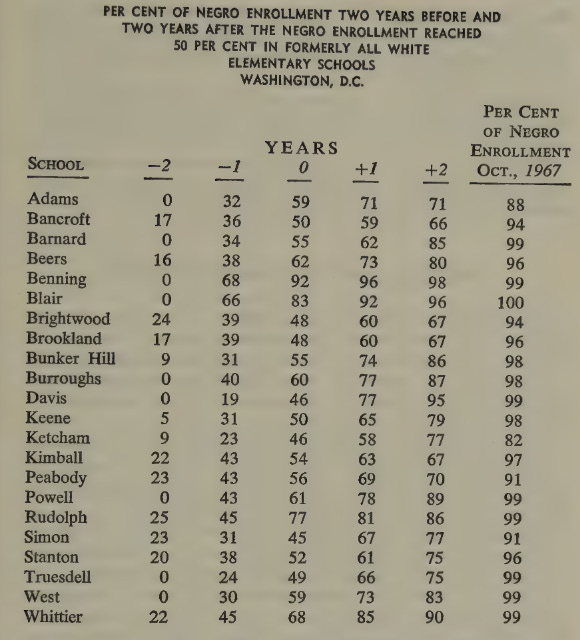

Less visible from raw numbers is the sheer difficulty individual schools had in maintaining integrated enrollment once they had it. School populations would turn over almost completely, with a few schools (like the District’s Eastern High School) going from 100 percent white to more than 90 percent black within a five-year span. Hansen noted that the tipping point seemed to be around 30 percent black, after which white flight almost always became rapid and near-complete.36

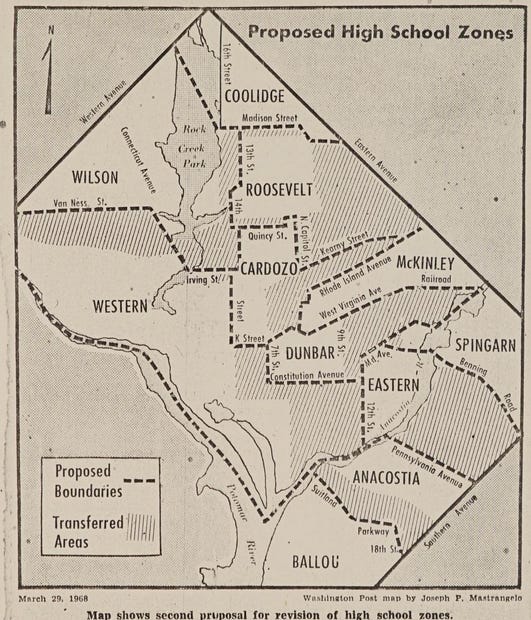

As a result of these population shifts, by 1960 white students were overwhelmingly concentrated in the wealthier areas west of the city’s Rock Creek Park, with the city’s Wilson High School remaining overwhelmingly white while more and more of the schools east of the park stayed overwhelmingly black.

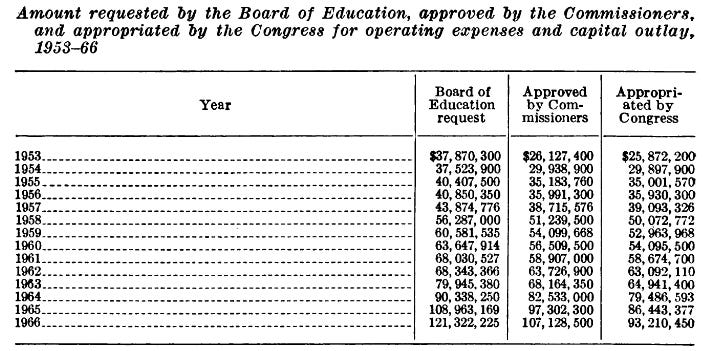

The school administration managed to secure more and more money from Congress each year, though never as much as it hoped. The budget went from $26 million in 1953 ($314 million adjusted for inflation) to $63 million in 1962 ($673 million adjusted for inflation).37 With Hansen driving things forward, the decade saw the introduction of new initiatives like a free lunch program in predominantly black schools, going from nothing to 8,220 lunches daily between 1952 and 1964.38 Accompanying this was a rapid expansion of services (librarians, counselors, and others) and special programs like a school for unwed mothers.39 With the District’s black student population more than doubling between 1950 and 1960, though, the schools struggled to keep up with demand.

Through the early 1960s, desegregation advocates regularly cited D.C. as an example of success. A Yeshiva University report on desegregation noted that “the integration of school systems has often been accompanied by a general upgrading of the entire educational enterprise, as in the District of Columbia.”40 Multiple 1964 papers on the effects of desegregation in schools cite Hansen’s D.C. numbers approvingly, noting steady gains among both black and white students.4142

Education historian Larry Cuban, looking back at this era of Hansen’s leadership, recounts it in glowing terms:

Between 1955 and 1962 Dr. Hansen led desegregation forces within the city, creating, in his words, "a miracle of social adjustment." Attacked in 1956 by a Southern-dominated congressional investigating committee, Hansen, then head of secondary schools, aggressively defended desegregation before the Davis Committee. He wrote, for no fee, two best selling pamphlets on desegregation for the Anti-Defamation League. In them he proudly pointed to the increases in black academic achievement and the improvement of interracial contacts.

After 1958, when he became superintendent and introduced first the four-track

organization and later the Amidon Plan, Hansen's prestige as an educational leader peaked. Appearing often at national human relations workshops, in demand as a national speaker on school desegregation, the superintendent was seen as an aggressive, no-nonsense schoolman. Time did two articles on him within six months. He had "begun turning the wreck of Washington's schools into a model that less beleaguered cities may envy." Saturday Review featured him as one of the nation's "movers and shapers of education." These and other articles stressed his achievements in avoiding the worst excess of desegregating schools that appeared to have befallen other cities. If there had been an educational Hall of Fame in the 1960s, Washington's white and black, would surely have installed Hansen because of his desegregation efforts.43

Overall, the atmosphere between 1954 and 1962 was one of guarded optimism: real challenges, a top-to-bottom transformation of the District’s student body, but a general determination to make things work and in Hansen’s case an eagerness to implement his vision.

But towards the end of 1962, everything began to come crashing down.

The Tracking Wars: 1962-1967

Beginning in 1955 or 1956, the District played host to an annual championship football game between the public school champion team and the parochial school champion. The game drew crowds approaching 50,000 people and was aimed in part at keeping white and black people coming together, celebrating, competing, and sitting in the stands. It became the community’s premier school sporting event of the year.44

On Thanksgiving Day of 1962, the predominantly black public high school champion, Eastern, faced off against the predominantly white parochial school champion, St. John’s, in a rematch of the 1961 championship football game in which Eastern won 34-14 in front of a crowd of 49,690. This time, St. John’s won 20-7 in front of a record-setting crowd of 50,033.45

But in the final quarter, a fight broke out. The elbow of a St. John’s player caught an Eastern player in the face during a blocking play without the officials seeing, the Eastern player drew back for a punch, and the officials ejected him. The Eastern player rushed back onto the field and began to attack St. John’s players. His teammates moved to restrain him, but new fights broke out between the teams. As the game ended, thousands of spectators rushed from the Eastern stands to the St. John’s stands, with more fights breaking out. The rioting spread to the nearby streets, culminating in hundreds of instances of personal or property damage and 42 officially recorded injuries.46

The game was cancelled the following year and all subsequent years but one, a 1972 revival attempt that drew a crowd of only 10,000. For many residents, the riot cemented an “us vs them” mentality, leaving scars on the city’s psyche for years.47 In its wake, Hansen commissioned a report from a biracial committee on the causes of the riot and potential solutions, determined to ensure nothing similar would happen again. The report focused on a need for discipline, noting that teachers were unsurprised and faced similar conduct in schools regularly, reporting that “many teachers too often become mass baby sitters for the young and wardens for the older groups” and that “too many pupils are passed upward from grade to grade, not because they have the academic ability, but only because they are getting older,” and called for an increase in various citizenship programs, school counselors, and personnel training.48

But of its 22 recommendations, one would stand out: a concern that the system’s basic track had become "a “dumping ground” and a “scrap heap” with inferior instruction, one in which many pupils would drop out and become “social dynamite” in the community. Many of the problems, the report noted, came from the basic groups at the high schools, “because those pupils have little interest or desire to advance.” The report called for a close examination of the track system, particularly the basic track.49

At the same time, American social critics, spurred by frustrations with a conservative presidency and a divided Congress, began a focus on urban reform, with the Ford Foundation on the cutting edge. Their funding and interest spurred a wide range of experimental education projects in ten school systems, including Washington’s, in the early ‘60s: team teaching, prekindergarten, community schools, and more. Larry Cuban, who started his career as a teacher within that D.C. reform movement, documents how the election of John F. Kennedy provided an opportunity for the reform movement to use federal money to tackle their priorities, with a new focus on the youth crime and that “social dynamite” of the slums leading Kennedy to establish the President’s Committee on Juvenile Delinquency and Youth Crime (PCJD) in May 1961.50

Washington Action for Youth (WAY), an organization funded by Kennedy’s PCJD, set up shop in early 1963, headed by New York social worker Jack Goldberg. Goldberg was a “dynamic and abrasive” character who believed passionately that institutions—especially schools—needed a confrontational transformation from outside to be set right. WAY believed that the institutions blocked opportunities for low-income kids who aspired to the good life and that they needed to become more relevant, more understanding, and more accepting of those kids—and in particular that schools were one of the chief causes of youth crime. In particular, Goldberg set his sights on the Amidon plan and the track system, Hansen’s signature projects. Both, Goldberg felt, must go.51

Goldberg chose the District’s Cardozo High School, whose principal was a close personal friend of his and a critic of Hansen’s administration, as the target area for an experimental subsystem of the school in which to try WAY pilot programs. He wanted the area for those reasons—and for the same reasons, Hansen did not. The dispute between Goldberg and Hansen over Goldberg’s goals of reform boiled over in public and private, culminating in Goldberg turning to the attorney general for what was supposed to be an ultimatum (“D-Day for Hansen”) in which things would either be done Goldberg’s way or Hansen could pack his bags and leave.52

But on the day the meeting was supposed to occur, Lee Harvey Oswald shot John F. Kennedy, Jr., and Goldberg was left suddenly rudderless. In place of his push for a confrontational and wide-ranging transformation, he agreed to a milder compromise focused primarily on a series of compensatory programs in the target area. Within six months, Goldberg resigned and went back to New York City. The Model School Division he aimed to create, a semi-autonomous and ultimately disappointing education reform project around the Cardozo High areas, wound up finding a less confrontational person to spearhead it, after which Hansen agreed to it not because he liked the idea but because he seized on anything that would get funds to his schools. While Goldberg left, his stinging critiques of Hansen opened the door for a dramatically more confrontational approach between activists, the press, and the Superintendent.53

And leading that charge was one Julius Hobson.

Julius Hobson was a passionate and focused activist with seemingly endless energy. Born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1922, he interrupted his studies at Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute to become a spotter plane pilot in the army during World War II. He moved up to Harlem after returning from the war, then down to Washington, D.C., where he studied economics at Howard University and found his lifelong passion.54 As he tells it:

The attitude was, we’re not going to hire these [n-----]s anyway for a job, so let them study anything they want to study.55

And what he wanted to study was Marxism. Recalling his graduate days, he noted that one of his teachers would introduce his courses with the statement that “a capitalist is a capitalist regardless of race, creed, or color,” that racism should be seen as a rationalization for economic exploitation, and that we could not hope to eradicate racism from the United States and at the same time maintain capitalism. As he saw it, black people could either “duplicat[e] the white man's mistakes by attempting to build an equally exploitative and racist black capitalism, or [internationalize] the struggle and mov[e] with the tide of the oppressed peoples of the world toward an economic system based upon the socialist economics of Karl Marx.”56

From that point forward, while he found day jobs first as an economic researcher with the Library of Congress, then as an economist and statistician for the Social Security Administration, Hobson lived for the struggle.57

Hobson’s most serious activism started when he became president of the Washington, D.C. chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). With them, he would picket automobile dealerships that would sell to black customers but not hire black clerks, stage “lie-ins” in white-only hospital wards, spread rumors that dangerous militants might come to protests. In 1964, his authoritative approach, militancy, and refusal to commit to nonviolence became too much for CORE, which kicked him out.58

From that point he started his own organization, effectively a one-man show: Associated Community Teams (ACT). At one point, suggesting Georgetown ought to share in the city’s rat problem, he drove through the city displaying a cage of rats and threatening to release them in Georgetown unless the city did something about the rats in the poorer areas of town. But it was in education activism where he really hit his stride.59

After years of increasing pressure against Hansen, Hobson hit the jackpot when his organization, ACT, filed complaints against the school system with the U.S. Office of Equal Educational Opportunities.60 This time, instead of being hauled in front of segregationists to explain integration, Hansen would be hauled in front of a committee to investigate whether tracking was discriminatory. After dozens of testimonies and days of hearings, the Congressional task force concluded with a report that recommended either revising the track system or dropping it entirely.61

When Hansen shrugged the report off, Julius Hobson turned to the courts.

Hobson Goes To Court: 1965-1967

Circuit Court Judge J. Skelly Wright was a formidable man—a lion of the court. Born in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1911, he taught high school history while attending law school during the Great Depression. He rose quickly through the ranks of the legal profession after obtaining his law degree, with his uncle appointing him to the staff of the US Attorney. In 271 cases he handled in eighteen months, he obtained 268 convictions. By 1949, President Truman appointed him as the youngest federal trial judge in the nation.62

Wright soon found himself in the middle of one of the most heated segregation fights in the nation, one that would see him issue injunctions against virtually the entire government of Louisiana. In 1956, after Brown v. Board, he ordered the New Orleans school board to come up with a desegregation plan “with all deliberate speed.” The board ignored him, dragging its feet until 1959, when he gave them a deadline of May 1960. When they came back without a plan in May 1960, he presented his own and ordered them to implement it by that fall—the first court-ordered school desegregation in the Deep South. The board members—all committed segregationists—dragged their feet, waiting for Louisiana Governor Jimmie Davis (composer: “You Are My Sunshine”) to save them and filing appeals—all of which were rejected.63

With the deadline approaching, Governor Davis and the legislature attempted to seize the schools from the board five separate times, only for Wright to meet them with restraining orders and injunctions every time. One order restrained 775 state and local officials. On Sunday, November 13, 1960, the day before the schools were to be desegregated, the legislature met for a special session, passing two resolutions aiming to place the entire legislature in direct charge of New Orleans schools. Watching the session on TV, Judge Wright signed papers enjoining the entire legislature and the Governor 45 minutes after the session. The schools desegregated. President Kennedy, seeing Wright torch any prospect of a peaceful future in Louisiana with his principled stand, appointed him to the D.C. Circuit Court in 1962.64

Supreme Court Justice William Brennan, a friend of Wright’s, praised him as one who believed that “judicial power should be made creative and vigorously effective,” while Wright personally emphasized that “in the area of equal rights for disadvantaged minorities . . . I remain an uncompromising activist.”65

Customarily, a circuit court judge would not hear a federal case until it was appealed. In this case, however, Hobson’s lawsuit included a claim against the system of federal judge–appointed school boards in D.C., making every member of the district court a defendant in the trial. The Court of Appeals appointed Judge Wright to hear the case.66

Hobson’s lawyers were similarly larger than life. To bring his case, he turned to the arguably most controversial and well-known lawyer in the country, militant left activist William Kunstler. Kunstler was proudly and explicitly ideological in his choices of client and case, saying, “I only defend those whose goals I share. I’m not a lawyer for hire. I only defend those I love.” Who did he love? During the early Civil Rights movement, Freedom Riders in Mississippi, on behalf of the ACLU. Later, members of the Revolutionary Communist Party, Black Panther Party, Weather Underground, and anyone else he could find in the radical movements of the ‘60s and ‘70s. He had a flair for publicity and a keen eye for opportunities.67

His co-counsel on the case, William Higgs, had previously defended freedom riders alongside him in Mississippi. Higgs had been a precocious student who took advantage of acceleration both in high school, when he skipped his senior year to enroll in the University of Mississippi, and in college, when he graduated in three years before heading off to Harvard Law School. He married and divorced within six months before being arrested and disbarred in Mississippi for allegedly having an affair with a 16-year-old boy. Rather than stand trial, he headed off to Washington, D.C., where he played a bit part in drafting the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as part of the Washington Human Rights Project before joining Kunstler on Hobson’s case.68

In October 1966, attorneys for the school district filed a motion asking Judge Wright to recuse himself from the case, arguing that he would not be able to preside over a fair trial in light of his prior commentary on de facto segregation. In a 1965 speech at New York University law school, Wright spoke against neighborhood schools and white flight, then made it clear that substantial racial imbalance was all the proof he needed to determine unequal educational opportunity. “I am aware, of course,” Wright said at the close of the address, “that what has been said here this evening will not find favor with the advocates of judicial restraint.” Wright declined the invitation to step back.69

The case, then, was unique from the beginning. It was “the only important one of its kind in which the NAACP did not participate,” brought by a militant activist with the help of “an equally militant lawyer,” and Hobson was suing over everything he possibly could. He sued because D.C. lacked home rule in appointing its Board, sued due to racial imbalance among teachers, sued because some District schools had “optional zones” where students could choose not to attend their local schools, sued over funding disparities. But most of all, he sued over the four-track system, and he did it all to demand the desegregation of a school system that was more than 90 percent black in the court of arguably the most sympathetic judge in the country.70

By 1966, Hansen’s formerly iron-strong hold on the District’s school board collapsed with the appointment of three new board members who explicitly opposed him. Most notable was the appointment of John A. Sessions, a former Cornell English professor and an education specialist for the AFL-CIO union, whose interest in “education parks” and distaste for Hansen set the stage for the destruction of the Amidon School.71

The argument went as follows: The Amidon School is high-performing and attracts some well-off students to its student body. Nearby Bowen and Syphax Elementary Schools are not. Therefore, we should combine them and make students from all three schools attend two years in each school, so that the well-off parents are inspired to help the other schools. Hansen proposed letting the schools decide; the Board shot him down.72

By November of 1967, reporters already noted that an overwhelming majority of the affluent families who attended Amidon had left. Hobson, reflecting on it, said, “They just don’t want their precious darlings to sit in the same classroom with dirty little slum kids.” 60 percent of Amidon students had been from public housing.73

In 1968, the “Tri-School” was judged “one of the ten best innovative education programs in the Nation” and “awarded a Medal of Achievement on November 19 at the National Laboratory for the Advancement of Education” for “Demonstrating Significant Changes in Teaching Which Measurably Improve the Learning Process.” At the National Laboratory, they showcased “how children in the Tri-School are motivated to learn by the discovery method and to explore and progress, each at his own rate.”74

Writing in 1970, the Washington Post’s prizewinning black journalist William Raspberry, considering the Tri-School Plan, called it an example of “hostage theory” in action. “The well-to-do parents would see to it that their children got a good education. All the poor parents had to do was see to it that their children were in the same classrooms. That was the theory. […] Now instead of one good and two bad schools, Southwest Washington has three bad ones.”75

“We moved from Virginia into Washington to get our children into the Amidon,” one mother said. “The handful of agitators that proposed combining the Amidon with the two other elementary schools hit below the belt. One of them said on television that the people who objected didn’t want their children to go to school with Negroes. We came to southwest Washington to put our children in an integrated school. We came back to Washington because we wanted our kids to go to school with Negroes—and poor kids.” They left the school.76

Judge Wright’s Decision (1967)

“All of the evidence in this case tends to show that the Washington school system is a monument to the cynicism of the power structure which governs the voteless capital of the greatest country on earth.” —J. Skelly Wright, Hobson v. Hansen (1967)77

Judge Wright’s decision in Hobson v. Hansen is a sprawling, fact-heavy ruling spanning more than a hundred pages, within which he settles most issues quickly and predictably: Yes, striking racial imbalance in faculty must be corrected. No, no more optional zones. Yes, funding is imbalanced in some schools.78

Having dispensed with those, he devotes the bulk of his attention to the track system. Judge Wright concludes that while Hansen was “motivated by a desire to respond - according to his own philosophy - to an educational crisis in the District school system” rather than intended racial discrimination, the district’s ability grouping served as “a denial of equal educational opportunity to the poor and a majority of the Negroes79 attending school in the nation’s capital.” In other words, he asserts that while Hansen did not apparently intend to discriminate, the system’s disparate impact made it unconstitutional.80

Much of Judge Wright’s decision rests on his objections to tests, which he treats as intended to uncover “the maximum educational potential” of students. “One of the fundamental purposes of track theory,” he claims, “is that students’ potential can be determined.”81 He condemns the use of aptitude tests on low income black children, because “the impoverished circumstances that characterize the disadvantaged child” make it “virtually impossible to tell whether the test score reflects lack of ability—or simply lack of opportunity.”82

The core piece of evidence Wright presents against these assertions is the “Lorton study,” a 1965 study in which young adult prisoners at the Lorton Youth Center, a D.C.-area prison for people between 18 and 26 years old, received instruction in reading and arithmetic over a one-year period. The inmates had an average IQ score of 78 on the verbal Otis aptitute test used in District schools and an average of 98 on a nonverbal IQ test, the Revised Beta Examination. After a year of focused instruction, the inmates went from average grade-level equivalents of 6.9 (end of sixth grade) to 8.2 (beginning of eighth grade) in reading, and from average grade-level equivalents of 5.6 (middle of fifth grade) to 7.4 (middle of seventh grade) in arithmetic.83

Per Wright, the study “reveals in hard fact that a disadvantaged Negro student with a supposedly low IQ can, given the opportunity, far surpass what might be expected of a truly ‘subnormal’ student,” demonstrating that the tests were poor measures of innate ability.84 As a result, he concludes that the administration was incapable of ascertaining the innate learning abilities of students and therefore could not justify placement of students in lower tracks.85 “The magic of numbers,” Wright noted, “is strong.”86

Wright objects that the track system’s fundamental commitment “is to educate ability, not just the student,” to create a “distinctly competitive atmosphere” that is unfair for students who are “born into a world where the color of their skin makes life an inevitable struggle to simply obtain equality,” and that it reinforces the psychological impact of being judged of low ability.87

As a result of all of this, he concludes that the effect of the track system is to unconstitutionally “deny a majority of District students their right to equal educational opportunity” and that it “simply must be abolished,” as must any system which “fails in fact to bring the great majority of children into the mainstream of public education.”88

(It’s worth re-emphasizing here that in practice, the track system meant at the elementary school level that some 3 percent of students were in special education and another 2 percent in honors classes, and that at the junior high level 7-16 percent of students were in special education and 6 percent in honors.)

Judge Wright leaves readers with a final thought:

It is regrettable, of course, that in deciding this case this court must act in an area so alien to its expertise. It would be far better indeed for these great social and political problems to be resolved in the political arena by other branches of government. But these are social and political problems which seem at times to defy such resolution. In such situations, under our system, the judiciary must bear a hand and accept its responsibility to assist in the solution where constitutional rights hang in the balance. So it was in Brown v. Board of Education, Bolling v. Sharpe, and Baker v. Carr. So it is in the South where federal courts are making brave attempts to implement the mandate of Brown. So it is here.89

I agree with Judge Wright that it was regrettable for him to act in an area so alien to his expertise. In the years since his ruling, scholars have raised serious critiques of his use of social science.

The most serious critique comes from a 1979 law review article by Donald Bersoff, who led joint PhD/JD programs in psychology and law after getting a psychology PhD from NYU and a law degree from Yale, and who would go on to serve as president of the American Psychological Association (APA). Bersoff argues that “from a psychometric point of view the court’s gravest error was its insistence that grouping can only be based on tests that measure innate ability,” something he notes no psychologist who writes on the subject believes.90 Bersoff further criticizes Wright’s condemnation of the tests as culturally biased, noting that the consensus view of psychologists is that when properly applied and interpreted, tests have predicted future learning for all segments of society with “modest but significant validity and generalizability.”91 Tests, Bersoff argues, effectively measures how well students have learned the skills taught by the school system—not measures of cultural or genetic inferiority, but effective documentation of current student understanding and needs. When widely used tests are carefully inspected, he notes, the standard finding is that they contain “legitimate samplings of quite uncontroversial educational goals.”92

Nor is there a free lunch waiting with culture-free tests or, in most cases, reduction of bias. Eliminating thirteen apparently biased items from an elementary reading test did nothing for the performance of schools with high minority populations. Deleting apparently biased items from group ability tests turned out only to make the tests more difficult for everyone, since the items tended to be lower in difficulty than others.93 Per Bersoff, claims of misprediction are not borne out either: studies examining predictivity indicate that “minority groups and people of lower SES are generally predicted just as well as are upper-middle SES Caucasians,” and the tests in fact sometimes overpredict success for minority students relative to white students.94

Bersoff was perhaps the best-qualified critic to address the point, but he was not the one closest to the case. That honor goes to David Kirp, founder and then-director of the Harvard Center on Law and Education, who worked alongside the ACLU as part of Hobson’s legal team for a subsequent stage of Hobson v. Hansen in 1971.95 In a 1973 law review article, while Kirp noted personal wariness towards ability grouping, he argued for judicial restraint due to its near-universality and its varied connotations.96 Per Kirp, “since individuals’ capabilities clearly differ, it would be a cruel hoax, a ‘deceit of equality,’ to premise a challenge to tracking on the argument that tracking caused school failure, implicitly promising that the educational differences would vanish if tracking were done away with.”97 Kirp also warned against abolishing tests, calling it “about as sensible as the ancient Greek practice of slaying the messenger who brings bad news,” and echoing the warning that minority children do poorly on “culture-free tests” as well as other ones.98

Christine H. Rossell, then a professor of political science at UCLA, in an article warning against careless use of social science research in educational equity cases, echoes Bersoff in drawing attention to Wright’s error in confusing the issues of achievement and innate learning ability for ability grouping. “The premise of tracking,” she noted, “is that, whatever the source of achievement differences, a student body characterized by variation in achievement requires a differentiated curriculum responsive to this variation. Whether or not tracking does serve these needs is the critical question, not whether it accurately sorts students according to innate ability.”99

She goes further still, making the single most damning point against Wright’s use of social science: “The court’s opinion […] reads like an exercise in illogic. It even cites as one of its justifications for abolishing tracking a 1967 [1965] research study of low ability, homogeneous (hence tracked) prisoners in Lorton penitentiary who with extensive remedial education showed a significant achievement gain at the end of one year. Not only is this not evidence of the evils of tracking, but indeed demonstrates exactly the reverse.”100

To repeat her point: as a core piece of evidence against ability grouping in K-12 schools, Judge Wright cited a study showing that adult prisoners in classrooms that were functionally ability grouped learned at a faster pace than one would have naively expected.

In his 2023 article The Magic of Numbers is Strong, psychologist Keith MacNamara, citing these critiques, notes that “any indication that the evidence was incomplete, uncertain, or subject to decades of debate did not register in the confident, often strident, tone of the opinion.”101

These errors are not unique to Wright—they are embedded in the Lorton study itself. The study has a few oddities, in one moment bragging that ninety-nine percent of applicants for the GED in its program are successful in obtaining it after a year of instruction102, while in another noting that the final reading level of some of its participants is within the range expected for second graders.103 It spends no time at all outlining how it actually taught students during that year of instruction while devoting lengthy sections to arguing against intelligence tests and tracking based largely on anecdotes.104 Reading the study, it comes across less as dispassionate research, more as an advocacy piece with a predetermined conclusion.

The Wright decision, then, stepped into an active and contentious dispute in the social sciences, misrepresenting the consensus of the fields while condemning as unconstitutional a pedagogical decision made on the basis of that same body of research without evidence of racial malice. As his core piece of evidence against the merit of testing and ability grouping, he used a study that used evidence of adults being tested, then learning well inside ability-grouped classrooms.

The Passow Report (1967)

At the same time Hobson v. Hansen was proceeding through the courts, the Passow team was conducting perhaps the most expensive, rigorous on-the-ground study of education in the history of Washington, D.C. schools. The same day the Hobson decision came down, Professor A. Harry Passow gave a press conference about the commissioned report.

A game of telephone has left modern secondary sources muddled as to what the report called for, with MacNamara (2023) claiming it “blamed many of Hansen’s policies for the deplorable condition of the school system” and that it “called for the end of the track system, the bussing of black children to under-enrolled white schools, greater integration of faculty, and an equalization of financial resources.”105 Reading his work and other secondary sources, I was under the impression that the Passow Report centered around condemnation of the track system. It does not.

Commentary on the Passow Report has, in fact, been so mangled since the day it was released that I believe it’s crucial to look at it in some detail. What did the most rigorous examination of D.C. schools, performed by a team of some of the era’s leading education researchers, have to say?

It’s an exhaustive document stretching well over 600 pages and covering every topic that could conceivably matter for the district, a dream opportunity for a team of researchers to specify exactly what they see as possible for a model school system. It’s not complimentary towards the system, certainly, noting that “the schools are not adequate to the task of providing quality education for the District’s children.” It cites low levels of achievement, a failure in many schools to follow grouping procedures, a high dropout rate, resegregation based on residential segregation, staffing problems, insufficient guidance services, inadequate testing procedures, inadequate teacher training, a weak promotion system, needlessly complex budgetary procedures, aging buildings, poor communication between schools and the community, cumbersome operating procedures in its Board of Education, and poor relationships with other youth-serving agencies. As I say, it’s a thorough report.106

The report is bleak towards the prospects of integration in the District schools in general, noting that in a system that was already more than 90 percent black, little was left to be done short of a return of the white population, so it advocated instead for a focus on quality instruction in a district serving overwhelmingly black and generally low-income students.107 In one part that would prove prescient, the report recommends against mandatory transfer of white teachers despite the predominantly white faculty at predominantly white schools and the predominantly black faculty at predominantly black schools, noting that the district’s teaching staff was already 80 percent black, that teachers dissatisfied with transfer may just leave the district, and that there was no evidence to suggest teachers could meaningfully transfer their skills from homogeneous groups to kids from widely different socio-economic and racial backgrounds.108

What the report does not include is opposition to ability grouping. Quite the opposite, really. “Differentiated instruction based on differentiated needs is at the heart of both equality and quality,” it notes early on.109 And later:

To live with this conception of equal opportunity, the community must be willing and the schools must be able to furnish unequal education. Unequal education to promote equal opportunity may seem a radical proposal, but it is in fact a well-established practice with respect to the physically and mentally handicapped under the name of “special education.” It must now be broadened to include unequal, exceptional education for every child who needs it.110

And again:

The starting point for good teaching is the recognition of differences, of learning disabilities, whatever their causes or origins, of individual talents and unusual potential for learning, of hidden aspirations and commitments. The fact of individual differences is fact. It cannot be ignored without seriously damaging the quality of education.111

And again:

In order to satisfy the youngster who requires compensatory education, the exceptionally talented child who needs greater challenge, the handicapped child with special needs, and the youth whose goal is immediate employment -- the schools would have to implement the long espoused American principle: each child should be educated according to his individual needs. What follows from this is that true equality of educational opportunity cannot result from identical educational treatment. ("The equal treatment of unequals produces neither equality nor justice.")112

When the report looks at the track system in practice, it is adamant that the District needs something very much like it:

Certainly by grade nine, the extraordinary range of academic performance would have imposed serious burdens on any teacher assigned to classes which included the entire range. The ninth grade Special Academic students seemed to perform four to five years below grade level, while the Honors students performed at about the mean for twelfth graders on both reading and mathematics. To attempt to gear a program to such different levels of functioning seems completely unrealistic.113

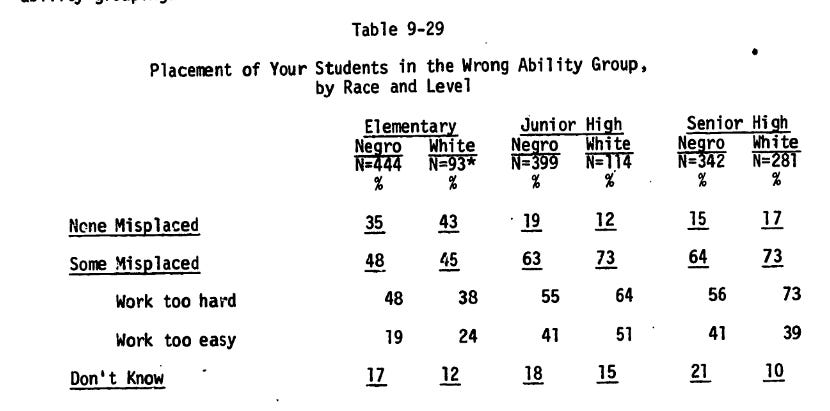

Were kids being left to languish in classes well below where they ought to be? Black and white teachers in the district were skeptical—at every level from elementary school to high school, black and white teachers alike were much more likely to claim the work in their classes was too hard for their students than too easy.114

The report advocates not for the removal of Honors programs but their expansion, lamenting that “too often, the few highly successful scholars are lost in the general population and tend to model themselves according to the aspirations and values of the majority,” and that “destroying the mechanism for challenging the most able students, especially those in the lower SES schools, and failing to reward them for high achievement is likely to lower their incentives for going on to higher education and greater social productivity.” It calls for Honors programs at every school in the District, even if different standards are needed school by school.115

In fact, one of the report’s complaints is that the Honors programs at the schools were insufficiently distinct from regular programs in curriculum and approach. “If honors programs are to serve the needs of talented pupils,” it warns, “they must be more than warmed-over regular courses.” It re-emphasizes this point when talking about math, noting that “one serious deficit in mathematics curricula is the lack of honest opportunities for mathematically talented pupils,” and that while relatively few people in the District were ready for advanced math, those who did warranted “extra attention.”116

The report laments the state of the system’s provisions for gifted students:

Ironically, concern for the disadvantaged and for racial balance has triggered opposition to what had become established and accepted practices for the gifted. Notably, special provisions for the gifted and especially special groupings have become a prime target for attack on the basis of alleged discrimination. […] With respect to both the gifted and the disadvantaged, the perennial question persists: "What sorts of education will best educate?" The provisions for the gifted and the talented have not been well conceived or implemented. The able youngsters in the District's population deserve better.117

In the end, the report sees the system’s tracking program as wholly unremarkable, noting that it “appears to differ little from the kind of ability grouping generally found in metropolitan high schools.”118 Theoretically, it notes that the system is distinguished by “rigid, city-wide criteria,” but in practice individual schools maintained individual criteria for their honors tracks, with the schools adapting to the needs and the reality of their student populations.

What of standardized tests? While acknowledging that “disadvantaged children are often handicapped in the test-taking situation itself by anxieties, lack of scholastic competitiveness and general unfamiliarity with the testing environment” and noting that test validity is affected by sociocultural factors, the report emphasizes that “such tests are still among the most important evaluative and prognostic tools available to educators.”119

So where do people get the impression that it calls for the end of ability grouping?

While the report emphasizes that “tracking practices by no means account for the grave difficulties of the school system,” it notes that Hansen’s system “is as often observed in the breach as it is in adherence to its basic tenets” and so recommends that “any form of a city-wide tracking, based on pre-determined city-wide criteria be abolished and that other plans for coping with the great range of pupil abilities, aptitudes, motivations and intentions be substituted.”120

Instead of Hansen’s system, in which schools started Honors and Special (formerly Basic) programs in fourth grade, the report recommended in-class grouping in elementary school and subject-specific ability grouping and honors classes in middle school and high school.121

That is: after finding that the only unique part of the system was a vision of rigid, city-wide criteria that did not play out in practice, the report advocated for the abolition of those criteria while emphasizing that schools absolutely needed to find some way to narrow the vast ability ranges they faced.

Instead of pointing to tracking as the District’s issue, the report hammers home again and again both the importance and the lack of instructional quality:

To the members of the task forces, one of the most distressing aspects of their experience in Washington was that they usually found themselves liking and respecting the members of the school staff as people of good will and devotion. But when they looked at what the staff was doing, they were often dismayed. It is likely that these same observers would be similarly dismayed if they were to visit other central cities. But Washington, our nation’s capital, deserves better — on behalf of all of us.122

This problem persisted at many levels: in Head Start classes, where children were surrounded by “warm and sympathetic adults” who nonetheless made “very little effort to provide a program that could be regarded as intellectually stimulating.”123 They recommended comprehensive retraining for teachers of young children.124

While the task forces liked the broad ideals of the Amidon plan, they noted that teachers were often inflexible and careless in translating those ideals into practice. In one arithmetic classroom, a teacher asked children how they would describe a commonality between a puppy, a chick, and a kitten. The kids unsuccessfully tried “fuzzy,” “farm animals,” and “pets,” which the teacher dismissed as incorrect without explanation, waiting for an answer of “baby animals” that never came. Because misinterpretations of the Amidon plan had been institutionalized, the report recommended abandoning it as a systematic plan and focusing instead on comprehensive redevelopment of basic teaching proficiency, as with teachers of younger children.125

The same pattern repeated again and again. On English, the report noted:

It is distressing to find English teachers with master’s degrees mispronouncing words, misexplaining workbook exercises on grammar, misdefining technical terms, and failing to catch consistent gross grammatical errors in oral speech. The observer could not escape the strong impression that a substantial portion of the English teachers were not themselves well enough educated in their own fields.”126

And with mathematics:

A principal weakness observed by members of the task force was the relatively low mathematical competence of both the elementary and secondary teaching staffs. With the few exceptions noted above, teachers observed seemed either uncomfortable with the material they were teaching or oblivious to its nuances and implications. Mathematical errors or misconceptions occurred frequently.127

What about science?

In many cases, students were carrying on activities in class which they did not understand and for which they could see no reason. Students were being led to believe that they were receiving high quality preparation for college. On the basis of papers the observers collected as a work sample, they doubted that the preparation now being given under the college-bound guise is adequate.128

In light of that, the report recommends—you guessed it—more teacher training.129

Washington Teachers Union President William H. Simons, seeing the report, noted that “the union takes strong exception to the implication that the District schools have a large number of unsatisfactory teachers.”130

Why do I belabor all of this at such length? Again and again in commentary around D.C. schools, the Passow Report and Hobson v. Hansen are treated as saying much the same thing about the schools. But only the most selective, surface-level reading of each can possibly support that. At the same time Judge Wright treated tracking as the original sin of D.C. schools, A. Henry Passow and his team looked at the district more closely than anyone before or since, shrugged at a grouping system that looked more-or-less like that of any other school system, and then pointed out all sorts of deep-running and difficult to fix structural problems that often came down to “it sure would be great if everyone was much better at their jobs.”

To understand what happened next, one must think like a school board. Between two recommendations for how to change schools, which one sounds more actionable?

A court order calling to abolish the practice of ability grouping, an approach already controversial among teachers and activists, then call it a day.

A 600-page report calling to comprehensively retrain teachers against the will of an unhappy union, overhaul the system’s curriculum, implement honors programs everywhere, provide more attention to disadvantaged and gifted students alike, and to refine the ability grouping program, all while juggling many other major concerns.

You may not be surprised, then, to hear the eventual outcome of the $250,000 ($2.5 million in 2025), two-year Passow Report:

After a year of study and dozens of meetings, the recommendations of the Passow Report and of the study group were quietly filed away.131

And the schools rolled on.

The Age of Hobson: 1967-1971

“When what you’ve spent a lifetime doing is suddenly being discredited and destroyed, you first begin to assuage your grief with self-pity.” So wrote Hansen as he looked back on the days in the wake of the Hobson decision. He worried about “an unholy alliance” between the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and liberals like Kenneth B. Clark, supporters of voucher programs for dissatisfied parents, that would lead to “farming out” a large portion of public schools to non-public corporations. He wondered whether his absorbing more of the blame for the D.C. school system’s failures might make the system of free public education “somewhat less vulnerable.”132 Finally, he elected to plead with the Board to allow him to appeal Judge Wright’s ruling. After the Board voted 7-2 against the appeal, Carl Hansen resigned as Superintendent of D.C. Public Schools at the beginning of July 1967.

Susan Jacoby wrote his career’s eulogy for the Washington Post: “The Superintendent Simply Stood Still.” Hansen had gone from facing segregationists down in the 1950s to becoming the villain of the 1960s, all without moving an inch. “There isn’t any mystery,” Jacoby wrote, “about what has happened with Carl Hansen. Policies that seemed liberal during the 1950s in a city that basically had been a Southern town seem very conservative today.”133 The New York Times added its assessment, noting that “few of Dr. Hansen’s critics seem to doubt his commitment to the cause of constitutional and human equality.”134

Despite his resignation, Hansen appealed the ruling alongside the one school board member who remained his staunch ally and twenty parents in D.C. Public Schools. The National Education Association announced it would file an amicus brief in support of Judge Wright’s decision, noting that “the [track] system was based on aptitude tests which are geared to white middle-class standards and thus work against disadvantaged students.”135 In its assessment of the case, the Civil Liberties Fund, writing in support particularly of the symbolism of the decision, included an aside that “in the abstract [ability grouping] has much to recommend it,” but that “all of the virtues and benefits of ability grouping upon which its proponents rely (and which one must concede are considerable) can be achieved in a track system modified in accordance with the Hobson opinion.”136 On appeal, the circuit court judges affirmed the ruling in a 4-3 decision, but narrowed it to abolishing strictly and specifically Hansen’s track system “as it happened to exist at a moment in time,” noting that the school board had wide discretion to ability group, “in light particularly of the detailed recommendations made in the Passow Report.”137

Left with little else to do, Hansen sat down and wrote a memoir, Danger In Washington. It’s not a particularly cheery read, but it is an informative one. From its preface:

What kind of book is this, then, that seems likely to be saturated with anger and shrouded with melancholy? Admittedly, what I have said as a preview here fails to convey my optimism about the capacity of American public education to weather the stormy period through which it is now going. What most encourages me is that in spite of everything, American social history indicates the eventual return to good sense and rational behavior from whatever extreme the educational pendulum may take. The public schools in this country will survive the danger in Washington. They will come through stronger than before, sharper in the services supplied, more fully dedicated to the objective of rational human behavior.

I hope this story of my work in Washington may contribute to the improvement of the public schools, America's most important social institution.138

Several dozen students from D.C.’s Western High School, most of them black, pleaded with the School Board and with Judge Wright to let them stay at Western despite the ruling against optional attendance zones. The ruling, they pointed out, would simply force them from a racially integrated school, would disrupt their college plans, and would ruin the school’s football team, yearbook, newspaper, and student council. In response, Hobson said he “sympathized” with the “handsome, nice, affluent colored ladies who sit here and cry about their children. But this is really of no concern. You are concerned your brown and white darlings […] are going to brush up against poor black children.” There will, he declared, be “no more private education in the District of Columbia at the public’s expense,” explaining that his suit “was not to get rid of de facto segregation as the press has reported,” but to “get quality education — it was to get poor black children into this rotten, lousy outfit called the United States.139

220 black students and only 35 white ones were impacted by the optional zone policy. Judge Wright relented and allowed the kids to return to their usual schools, which infuriated Hobson: “If the judge wants to back off, that is all right. But, he better realize that he is yielding to the same economic and racist pressure and discrimination he condemned in his decision.” Referring to the predominantly black parents who petitioned the judge, Hobson said, “It’s not the white racists and bigots to watch out, but the black ones.”140

The next serious conflict came when the Board named its next superintendent: Dr. William R. Manning, a white man from Michigan, after the only black man among the top candidates withdrew his name.141 Hobson and his militants disrupted the meeting with shouted opposition, a pledge of “equal education or equal chaos,” and a demand to “vote black.” “Maybe Mrs. Allen doesn’t know she’s a Negro,” shouted one of Hobson’s militants when she pushed back against the demand. “Maybe she should look in the mirror and find out what she is.”142 Hobson declared his intent to sue to stop what he called a “racist decision.”143 He later made good on his promise, alleging among other things in the suit that Mrs. Allen was ineligible to be a board member because of her work in the Office of Education.144

The next month, Hobson gave a speech at a Howard University symposium advocating that the students there direct their efforts toward the downfall of capitalism, with revolutionary force if necessary.145 His revolutionary fervor, though, stayed mostly contained to efforts to disrupt the school district, as when he pressured them to cancel a reception to install Superintendent Manning on the grounds that it used public money for a non-public function.146