Freddie deBoer is Wrong and Education Reformers Must Care about Learning

Moving beyond anti-capitalism in education policy | Theories of Progress, 01

Freddie deBoer believes that most of us are confused about what we care about in education. We think that we care about absolute learning — that we want students to learn new skills, content, and concepts, improving their performance relative to benchmarks. But deBoer claims we only think that we think that. “We say we care about absolute learning, but what we really care about is relative learning.”1 Relative learning is a student’s learning measured against the performance of her peers. For deBoer, “relative learning is practically and morally dominant” over absolute learning, because “only relative learning … can better one’s economic fortunes,” and it is this that we really care about.2

No matter how confident we may be that we grasp this difference, sincerely believing we value the learning of skills and content more highly than whether students outpace their peers, deBoer insists we are mistaken. “No matter how much you might want absolute learning to matter most, you will always end up caring about relative learning.”

The primary targets of deBoer’s charge have been education reformers who want schools to close achievement gaps while at the same time denying that students differ in innate academic ability. Yet when he minimizes the importance of absolute learning, he doesn’t qualify that he is just speaking to these reformers. He is speaking to you, too: you may think you care about absolute learning, but if so, you are mistaken.

While deBoer offers an incisive critique of gap-minded reform, his dismissive attitude toward improving absolute learning follows from a moral outlook that warrants suspicion. deBoer’s targeted reformers seek to close achievement gaps in the interest of equality. If weaker students gained ground on their high-performing peers, the disparity in economic benefits would not be so dire between low and high performers. But while deBoer shares with his targets the interest in improving economic outcomes for low-performing students, he has abandoned hope that education can facilitate this improvement. Accordingly, when deBoer offers policy recommendations in the context of education debates, these recommendations largely sidestep pedagogical matters. In his most recent platform, deBoer’s recommendations are:

Crafting multiple paths to graduation with different standards, such as substituting statistics for algebra;

Improving air quality (which can get very bad and produce very real negative effects);

Implementing “soft” tracking to direct students into curricula that benefit their skills and interests; and

Establishing a stronger social safety net that makes material security and dignity less dependent on a degree.

Whether or not we find these proposals sensible, it is a striking fact that such a prominent voice in American education policy has so little interest in discussing how to increase student learning. Now, increasing learning can mean either increasing absolute learning or increasing relative learning. In deBoer’s view, increasing absolute learning is immaterial to the moral outcomes that matter, and increasing relative learning is impossible — and therefore also immaterial to the moral outcomes that matter. We are left, therefore, with a peculiar view on which increasing learning is irrelevant to what matters in education policy.

This approach should probably be rejected, then. But the problems with deBoer’s views go deeper than a lack of focus on actual education. As I see it, there are three key failure points in his general theory.

First, the benefits of absolute learning are not as meager as deBoer suggests. His moral outlook casts them as less important than the benefits of non-learning interventions, and so he downplays what absolute learning can offer a society and its lowest academic performers.

Second, deBoer resists prioritizing absolute learning because of assumptions that we should reject. While he recognizes the value of the performance of the top ~5% of students, he nevertheless curiously and persistently rejects the value of absolute learning. His objections are thus deeper than merely believing that increasing absolute learning will not address inequality, or even increase it: they are based in utopian misreadings of the roles that skill-based desert and normal human incentives play in a meritocracy. Moreover, policies prioritizing absolute learning gains are not only consonant with deep progressive policy goals, but likely conducive to them as well.

Third, we cannot agree to the terms of deBoer’s thought without indulging his apathy toward the well-being of high-performing students. In his view, strong students will accrue material reward and dignity unavailable to weak students, and so the former’s flourishing is to be taken for granted and the latter’s as our abiding concern. The idea that a high-performing student could be miserable because she is not being challenged in the classroom is, if not unthinkable, uninteresting.3 Whatever her plight, our society still overvalues academic ability. And the route from intelligence to success is direct and uncomplicated.

deBoer’s approach suggests that education reform is zero-sum — that if one focuses on his priorities, there is no space in the conversation for a focus on increasing learning. But whether you are a believer in meritocratic capitalism or a deeply sympathetic social democrat, you have good reason to be interested in learning, regardless of what jaded utopians insist.

The learning skeptic

If you value education as a vehicle for equality, then increasing absolute learning for students will not give you what you want. This is deBoer’s essential point. Educational equality would mean closing the gap in relative student achievement between low- and high-performing students, and this would require increasing the performance of low-performing students to a greater extent than that of high-performing students. Yet deBoer emphasizes that gap-closure reformers resist two inconvenient facts.

First, widespread empirical evidence shows that individual achievement gaps reflect differences in innate academic potential, and so students’ relative positions in the performance distribution generally persist throughout their education. Second, any pedagogical technique that increases learning for weak students also increases learning for strong students; there is no “magic bullet” that only serves weak students (besides the nonstarter of reserving effective methods for weak students and using poor methods for strong ones). If all high- and low-performing students enjoy comparable gains in absolute learning, then the relative positions of the low performers goes unchanged.

Even if we can’t increase relative learning, though, perhaps we can still hope to increase absolute learning across the board: if every student’s academic performance increases, should we not celebrate the general increase in knowledge and capabilities? The Flynn effect — the widespread increase in average IQ across the developed world in the 20th century — strikes us as a good thing, and the reverse Flynn effect — the widespread drop in average IQ in recent years — strikes us as a problem, even if the increase and decrease in absolute IQ scores leaves the relative gap between the best and worst students unchanged. If these intuitions correspond to what matters, surely we should strive to increase absolute learning for all if we can.

But for deBoer, these intuitions are off track. What really matters for education is not absolute learning but relative learning, because “it is relative academic performance which is rewarded in the labor market, and it is thus relative academic performance which has social justice valence.” Weak students compete with strong ones on the job market; if weak and strong students improve by the same absolute degree, employers will still prefer the strong ones, and the weak students still lose out. Since relative learning would improve the rewards of weaker students on the job market, this makes relative learning “morally and practically dominant.” But increasing relative learning is impossible, at least as a matter of practical policy.

On the other hand, absolute learning may be possible, but in deBoer’s picture it simply does not have what he calls “social justice valence.” Such valence attaches because the stakes of one’s material wellbeing, as a general rule, depend on succeeding or not succeeding in education, and here it is not absolute ability but one’s ability relative to the competition that matters. For example, if you think the top 10% of the world’s electrical engineers are paid for their absolute performance, notice with deBoer that if they “were taken by the Rapture tomorrow, the next 10% would get the compensation that went to the now-disappeared 10%.” If you care about achieving educational equality, it is not because you care about improving learning per se, but rather because you want to ameliorate the inevitable material suffering in store for weaker students. “Simply reforming the education system can never fix what’s broken,” he writes, “because the problem is not with educational outcomes but rather how educational outcomes lead to economic outcomes in our system.”

Also, quit searching for pedagogical silver bullets to improve struggling students’ prospects — even if modest gains in absolute learning are possible, “the effect sizes just aren’t that big.” Don’t fiddle with curricular levers of dubious efficacy when you can focus instead on political solutions to improving material outcomes for the least well-off directly. Focus on minimizing poverty, ensuring a social safety net, and providing non-degree paths for weak students to the middle class, and stop wasting time with educational interventions. Education won’t affect students’ relative positions, which means education will not achieve the social transformations you actually want.

The good of learning

To persuade the education reformers who want to eliminate gaps, deBoer addresses two central disagreements. The first is a straightforward, factual disagreement about whether absolute learning is useful for their moral agenda, and deBoer argues it is not. The second is an evaluative disagreement over the true goal of their kindred moral agendas: deBoer argues that what they think they care about — educational equality — is unachievable, but what they should about — ensuring a minimum of material well-being — can and must be accomplished through redistribution.

But some readers will find that something they care about in education has been missed. Some might believe that education is not important just for increasing the wages that students will earn, but for improving the skills and expertise that improve the goods and services that students will earn those wages for. Let us grant with deBoer that if both low- and high-performers learn 10% more, their relative compensation goes unchanged. But if every electrical engineer were 10% more competent, power grids and electrical systems would presumably run more efficiently than if run by the less-skilled. If every doctor knew 10% more about diagnosis and treatment, patients would receive better care for the same cost. These benefits are not hard to explain, but a model that focuses exclusively on compensation renders them completely invisible. We may believe that more must be done to improve the material conditions for the worst off among us, but if we value the accomplishments of skilled and knowledgeable work across domains, we should not temper our support for improving absolute learning just because it does not also resolve our other concerns.

Sometimes deBoer seems to recognize the importance of developing the absolute learning of top students. In The Cult of Smart he points to research that suggests “what really matters” for a country’s economic growth is “the academic performance of the top 5 percent of students.”4 As the authors explain, “the cognitive ability of the 95th percentile of the population (the intellectual class)… is a more important predictor of a nation’s wealth” than mean national cognitive ability, for two reasons: the ability level of an intellectual class (1) has a “direct influence on national excellence in scientific achievement and technological progress,” and (2) “chang[es] economic and political institutions in a more liberal, democratic, constitutional, and efficient way.”

Now, both STEM achievements and economic freedom are the results of absolute performance, not relative performance. Unlike the compensation for the top 10% of electrical engineers in deBoer’s example, there is no fixed pie of STEM achievements, a larger slice of which would magically accrue eureka-style to the next minds in line if the top tenth were raptured. Neither does the wealth of nations increase based on their institutions’ relative economic freedom, but by becoming “liberal, democratic, constitutional, and efficient” in absolute terms. Given that the cognitive ability of the strongest students equips them to produce scientific advancements, technological innovations, and economic institutions that drive increasing prosperity, we should absolutely remain committed to improving their absolute learning gains!

In their recent riposte to his criticism of their coverage of the Southern Surge, Kelsey Piper and Karen Vaites suggest deBoer’s support of “the intellectual class” thesis should provide common ground for supporting efforts to increase absolute learning à la Mississippi. In Mississippi, the percentage of fourth-graders attaining the highest score on the NAEP reading test has increased from 3% in 2013 to 7% today. With this much improvement in the performance of the state’s top students, then someone like deBoer — who thinks “what really matters” for economic growth “is the academic performance of the top 5 percent of students” — should be more sanguine about Mississippi’s approach.

Yet when deBoer introduces the research on “the intellectual class” in The Cult of Smart, he does not do so to encourage absolute learning for strong students. Rather, he deploys this data in The Cult of Smart for precisely the opposite purpose: to counter claims that improving educational performance has either economic or social advantages. When ed reformers lament low PISA scores and advocate improving American schools, they wrongly assume “a strong connection between education and economic growth.” If the only learning outcomes that matter for economic growth are those of the top 5%, then the economic impact of learning outcomes for the bottom 95% is negligible. And since America’s top performers are already “the envy of the developed world,” deBoer writes, reformers’ calls to improve education for economic reasons are baseless.5

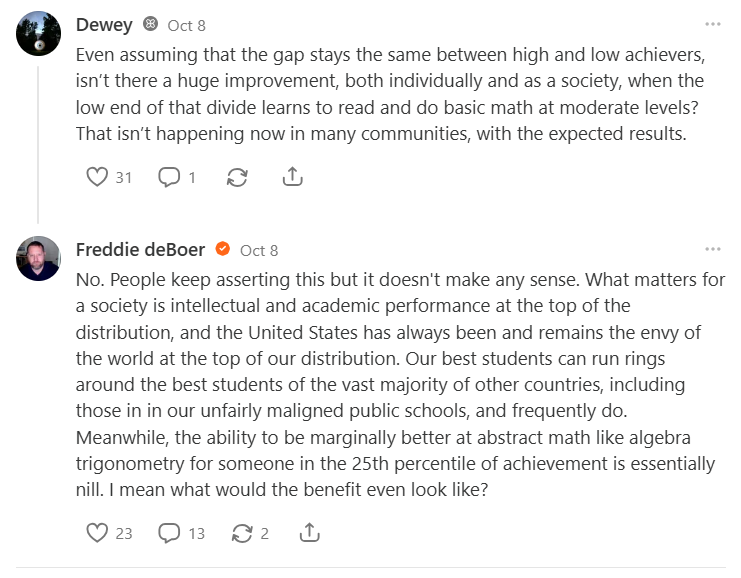

This deployment is not a relic of deBoer’s earlier work; in a comment thread downstream of the piece by Piper & Vaites, he uses the same point for the same purpose:

Elsewhere, deBoer has no trouble writing that “There’s all sort of benefits that we can identify that might come from everyone getting more educated,” and that “certainly there would be some positive effect on the economy and society if everyone did better in school.” When engaging directly with calls to increase absolute learning, however, this is a positive effect that one can hardly imagine: “what would the benefit even look like?”6

Neither do deBoer’s thought experiments reassure us that his reliance on this data reflects a sincere interest in the absolute performance of top students. In one colorful illustration, he imagines Harvard’s incoming class being abducted by aliens, and the university admitting a replacement class from the next-best performers. Assuming the abductees had been admitted for being the highest absolute performers, the replacements will necessarily have lower absolute academic ability. Yet despite this lower absolute ability, and despite the now marginally reduced gap between the lowest and now-highest performers, upon graduation the replacements will still “receive the advantage that a Harvard degree confers in the labor market,” because they “would still be perceived as the cream of the crop relative to their labor market peers.”7

Were this the example of someone who seriously valued the academic performance of the top 5%, we should perhaps expect a caveat that the abduction represents an outsized loss in productivity and innovation, not just a meaningless blip leaving the labor market unchanged. Instead, it is the example of someone for whom the achievements of top performers are fungible and abundant, if not beneath concern entirely. It is difficult to make sense of deBoer’s responses above as disagreements about facts alone. Understanding his campaign against absolute learning requires understanding how it is motivated by a disagreement about values, too.

deBoer’s Cult of Smart

The Cult of Smart offers some more insight into why deBoer is uninterested in absolute learning. The reason is not just that he is skeptical of the effect sizes of pedagogical interventions, although this is certainly true. At least as important as this skepticism is his rejection of what he sees as the dominant moral paradigm in a meritocracy. In one respect, meritocracy is the notion that jobs should go to those who perform them well. But when this notion is debated on moral grounds, defenders and detractors alike often appeal to the idea of “skill-based desert,” i.e., that anyone can be said to deserve their livelihood or success in virtue of the skill they exercised to achieve it.

deBoer develops a critique of skill-based desert that begins as a narrower critique of his book’s namesake, the “Cult of Smart.” The Cult of Smart has three basic components:

A societal overvaluation of intelligence relative to other human skills. Judgments of intelligence seem uniquely tied to judgments of innate worth in a way that, e.g., judgments of athletic and musical ability are not. Vividly, “A child who’s really bad at sports is amusing; a child who’s really bad at school is a crisis.”

A belief that education is the key to fixing poverty, unemployment, and inequality.

A belief that eliminating environmental barriers to academic achievement would lead to a just meritocracy in which those who work hard and succeed academically obtain the livelihood they deserve.

The Cult of Smart presents a provocative explanation for the resistance many gap-closure ed reformers have to accepting innate differences in academic potential. For someone who believes intelligence is uniquely tied to human worth, accepting innate differences in intelligence is tantamount to the morally reprehensible belief in innate differences in human worth. Further, so long as these reformers — mostly successful students themselves — believe that any student can succeed academically with the right environment, they can rest easy believing in a system of just deserts, wherein the students who work hard will succeed deserve their success, and those who don’t succeed could have, if they had only worked harder.

If many students are innately limited in academic ability, however, then no matter how hard they work, they will still likely not experience academic success or the livelihood that follows. Because students do not choose to be born with low or high academic potential, deBoer argues that students cannot be said to deserve their academic success or the ensuing relative material abundance waiting for them on the job market. Thus, the justice of meritocracy is an illusion: if the distribution of wealth correlates with the distribution of intelligence — a skill no one chooses — then the distribution of wealth is likewise unchosen, unfair, and immoral.

deBoer makes clear he is not opposing American meritocracy for falling short of an ideal form, but opposing that moral ideal directly:

“What could be crueler than an actual meritocracy, a meritocracy fulfilled? Because once we acknowledge that natural talent exists at all, even if it were a minor factor, the whole moral justification of the edifice of meritocracy falls away. No one chooses who their parents are, no one can determine their own natural academic abilities, and a system that doles out wealth and hardship based on academic ability is inherently and forever a rigged game.”8

Just as we do not choose whether we are intelligent, so the argument goes, neither do we choose whether we have any remunerable skills at all. If no one chooses to be born with the skills that can earn a good living, then the skillful are no more deserving of their economic success than the unskilled are deserving of their pittance. It is not just that our society overvalues intelligence relative to other skills; it is that our society overvalues skill itself as a grounds for moral desert. In a discussion with Agnes Callard, deBoer states his view succinctly:

“When we’re talking about reward, when we’re talking about how society hands out lifestyles and material security, it’s never been clear to me exactly what the fundamental principle is that says that we should necessarily reward people who are good at things more than people who aren’t.”

The view that the skilled are no more deserving of higher incomes than the unskilled directs deBoer’s focus when it comes to potential avenues for reform. If intelligence is already overvalued, and not a justifiable basis for deserving a comfortable livelihood anyhow, then encouraging schools to update pedagogy and curricula for the sake of improving learning outcomes is a non-starter: improving learning is morally bankrupt given the economic system we operate within, so focus your efforts on implementing a more robust social safety net. If education cannot improve access to higher-paying jobs for low performers, and if it is wrong to think income should correspond to performance, then we must likewise sideline the development of student skills in favor of redistributive policies.

deBoer’s views on education, we see, are not limited to skepticism about the effect sizes for pedagogical interventions. Even if we discovered a way for all students to learn twice as much, why should we care? Increased learning and skills do not change students’ place in the relative distribution, and whether students solved problems or achieved something with that knowledge and those skills would be irrelevant to the material conditions to which they are entitled.

The value of skills

Before we allow deBoer’s critique to turn against the value of absolute learning, we must first explore a tension in two ways deBoer has framed the story he tells in The Cult of Smart.

One way begins with morality. That the social fixation on education and intelligence is cruel. If academic potential is inherent, then valuing people on the basis of academic potential is unfair. This fixation “inevitably devalues human characteristics that should not be devalued, such as compassion, perceptiveness, patience, thoughtfulness, kindness, depth, and curiosity,” and we must object to any social arrangement in which such valuable attributes are not given due moral weight.

Another way begins with economics. The 20th century saw the loss of factory jobs that paid a good wage for physically demanding work and high manual competence. When these jobs disappeared, we saw a greater concentration of jobs that paid for mentally demanding work and high intellectual competence. This inevitably led to a higher social valuation of generally useful intellectual ability, and to education as an institution that trained and certified that intellectual ability.

The second story, which reflects deBoer’s Marxist view that economic forces drive culture, points to a problem with the first story. The first story tells us we should not overvalue intelligence because it leads us to devalue other valuable things, and suggests we must intervene at the level of moral judgment: we must change what we value. But the second story explains what we value as the result of economic realities: people value professional competence, and as the proportion of professions in society demanding cognitive competence increased, so too did the value we place on cognitive competence.

We may lament that there are not more high-paying professions for other forms of competence, but if deBoer is right when he claims economic forces drive culture, and it is the economic value of intellectual ability that best explains the social valuation of intelligence, then dissuading us of the value of learning on moral grounds is an uphill battle, to say the least. (Fighting against the forces of production, as Marxism so often reminds us, can be quite challenging.)

deBoer’s moral story is at its most compelling when the economic story takes a back seat. Consider the anecdote deBoer uses to illustrate the social overvaluation of intelligence of a mother discussing her two sons:

She was talking about her older son with obvious pride, with obvious pride, describing his achievements in his robotics club, how well he always did in math. And then her younger son ran by, and she said, offhand, “This one, he is maybe not so smart.”

I was taken aback and wondered initially if maybe something had gotten lost in translation. But … [t]here was no reason to think she loved her younger son less. She simply accepted that he had different strengths than her other son. Had she said that her son didn’t have an artist’s temperament; had she said that he would never be an athlete; had she said that he didn’t have an ear for music—I never would have thought twice about it. It’s only with intelligence that we have such massive hang-ups, only intelligence that we treat as the sole criterion of someone’s worth.

The anecdote has power because it compels moral self-interrogation. We notice that we, too, are taken back when the mother says her son is “not so smart,” but that we, too, would not have been shocked had she denied his artistic, athletic, or musical skill. We ask ourselves what explains our contrasting responses, and deBoer answers ideology: we have wrongly granted to intelligence an overriding moral value that we deny to other strengths.

Yet when we recall the economic story, this power disappears. Yes, artistic, athletic, and musical excellence are demanding, enriching, and inspiring, but at the same time their economic applications are narrower. Intelligence, in contrast, is useful across a wider variety of professional domains (including in sports and music themselves!). Tennis skills in the 90th percentile have much less pull on the job market than cognitive skills in the 90th percentile; thirteen years of deliberate practice in the violin are invaluable for playing the violin well, while thirteen years of deliberate practice in mathematics, foreign languages, or physical sciences imparts knowledge that can be used across many domains. Don’t forget, either, that once deBoer’s critique moves from the overvaluation of intelligence to the overvaluation of skill generally, any moral force gained by championing other excellences is lost: visionary artists, excellent athletes, and expert musicians deserve no more professional success than their unskilled counterparts.

And is the advocacy of excellence — educational excellence, but also musical excellence, athletic excellence, and excellence of any kind — immoral in virtue of one’s capacity for that excellence being unchosen? The answer relies, crucially, on seeing that deBoer treats meritocracy as fundamentally a system of moral justification rather than of socio-economic incentives. When deBoer speaks of meritocracy, he speaks of society “doling out wealth and hardship” of material security and cultural capital on the basis of judgments of worth, judgments which are morally unjustifiable because they are based on unchosen factors like intelligence, innate talents, or other skills. But as Scott Alexander explains in his review of The Cult of Smart, meritocracy is not a “reified Society deciding who should prosper” on the basis of desert, but instead “a dubious abstraction over the fact that people prefer to have jobs done well rather than poorly, and use their financial and social clout to make this happen.” Alexander presents the wages of surgeons as an example:

Your life depends on a difficult surgery. You can hire whatever surgeon you want to perform it. You are willing to pay more money for a surgeon who aced medical school than for a surgeon who failed it. So higher intelligence leads to more money. … More meritorious surgeons get richer not because “Society” has selected them to get rich as a reward for virtue, but because individuals pursuing their incentives prefer, all else equal, not to die of botched surgeries.

If the decision to seek a competent surgeon is not an immoral one in virtue of not choosing the lesser surgeon, then neither is it immoral to prefer competent workers for valuable positions or to wish to promote skill-building in education.

deBoer values improving the lives of the unskilled. He is compassionate for those he feels the system leaves behind, and indignant that those who do well under this system do not share his moral outrage for the plight of the rest. Sentiments, however, are frequently imperfect justifications for social policy.

Disagreements about facts, disagreements about values

Although deBoer at his strongest argues that we should do away with the notion of desert altogether, his positive vision still relies on it. He regularly appeals to the idea that “everyone deserves certain minimal material conditions” required for human flourishing. Flourishing is an appealing moral concept: it names something richer than pleasure or utility, suggesting a life animated by virtue, purpose, and human excellence. You might doubt that my pleasure carries moral weight, but if you sincerely judge that I am flourishing, your judgment carries a certain kind of moral endorsement.

When deBoer claims that America’s Cult of Smart robs low-performing students not just of comfort, but of their ability to flourish, he asks us to question whether the pursuit of academic excellence undermines the possibility of other human excellences. His goal is to persuade reformers to abandon their faith in academic interventions that do little to improve material outcomes for low performers and to redirect their energy toward non-academic reforms that will. In this system, the flourishing of weaker students depends on social rather than scholastic remedies.

For high-performing students, however, deBoer’s account becomes two-dimensional. On his zero-sum model of academic performance and economic success, strong students have already “won” the contest for material reward. Since they will prosper regardless, there is no reason to push them toward greater achievement. Kids who do well in school do well in life, full stop. There is no exploration of whether they might have deeper needs, or whether certain forms of schooling could uniquely enable their flourishing. By treating academic success as sufficient for their well-being, deBoer defines them as “already flourishing” by default.

But appeals to flourishing cannot so easily sever the link between flourishing and the development of excellence. deBoer rejects meritocracy because he denies that moral desert should track merit or accomplishment, yet desert clearly intervenes somewhere in the claim that every person deserves what is necessary to flourish. If flourishing means realizing one’s potential, it cannot mean the same thing for everyone. Students differ not only in ability but in the kinds of excellence available to them. For some, flourishing may mean achieving stability or belonging; for others, it may mean pushing the limits of intellect and creativity.

And if educators are morally obliged to give each student what they need to flourish, that obligation demands differentiated attention. A high-performing student who is unchallenged, bored, or under-taught is as surely deprived of flourishing as a struggling student denied basic support. The high achiever may “deserve” more, not fewer, academic resources, precisely because her flourishing depends on richer intellectual challenge and deeper mastery.

The costs of labeling the top-performing students “already flourishing” are not just borne by the students themselves. As deBoer sometimes reminds us, these high achievers are the very students whose academic flourishing we most rely on for our scientific, technological, and economic progress. When they are pushed to flourish at their maximum potential, we — all of us — are among the beneficiaries.

In The Cult of Smart, deBoer asked us “What could be crueler than an actual meritocracy?” One answer would surely be a system in which skill is no more desirable than the lack of it.

The Cult of Smart, [1:28:20].

Education Doesn’t Work 3.0 and The Cult of Smart, [1:28:20].

“The fear that the highest-achieving students won’t learning [sic] what they need to is an artificial one; the highest-achieving students are self-motivated and will self-select into the difficult, abstract classes anyway, and in fact already do.” Education Doesn’t Work 3.0.

The Cult of Smart. Chapter 1.

deBoer cites Heiner Rindermann and James Thompson, “Cognitive Capitalism: The Effect of Cognitive Ability on Wealth, as Mediated Through Scientific Achievement and Economic Freedom,” Psychological Science 22, no. 6 (2011): 754–763.

Note how deBoer here transforms “doing basic math at moderate levels”( including basic statistical literacy) — for which he advocates! — into “the ability to be marginally better at abstract math like algebra and trigonometry.”

The Cult of Smart, Introduction.

Thanks for linking our previous retort to DeBoer. He's so inconsistent, I'm not sure he's worth the time put into all of this! Curious whether people think his contrarian takes are having much influence on the education discourse.

Freddie's ouevre can generally be summarized in six words:

Always provocative, frequently interesting, rarely wise.

The two exceptions are when he writes about psychiatric issues and education, where I think he has arguments that are worth fully engaging with. Appreciate you having done so here.