Exceptionally Gifted Children

Learning from the brightest youngsters | Theories of Progress, 02

The research is clear: academic acceleration benefits faster learning students academically, socially, and emotionally. Even so, American schools routinely deny it. Guest contributor John Boyle synthesizes findings from Miraca Gross’s 20-year longitudinal study of 60 exceptionally gifted children and Leta Hollingworth’s pioneering work at the Speyer School to show what happens when schools force brilliant children into lockstep education, and what we should do instead.

John Boyle is a programmer for a Silicon Valley data storage company. He has a lifelong interest in education in general and gifted education in particular.

The Exception that Proves the Rule

Adrian Seng was a remarkable boy. He learned to read before age 2 by watching Sesame Street. By age 3, he had the reading, writing, and math abilities of the average 6-year-old. At age 5, he had learned math up through grade 5 at home, all before entering school. An IQ test at age 6 yielded the scores of a 14-year-old (his “mental age”); since 14/6 ≈ 2.3, his “intelligence quotient” was therefore 230.1

His school’s response? They didn’t make any special effort, but simply let him keep moving up to the grade level that was appropriate for him in each subject. Thus, at age 6.5, he was attending grades 3, 4, 6, and 7 in different subjects, and had friends in each of those grades, with whom he played in the schoolyard. At 7.5, he started spending part of his day in high school, doing grade 11 math; at 8, this became four high school classes and some elementary school; at 8.5, he’d finished elementary school completely, and, at 9, he devoted a quarter of his time to studying math at a local university. As he mastered each high school subject, the fraction of time spent at university grew until, at age 14, he had completely finished with high school. At 15 he had the college credits for a bachelor’s degree, and at 16, he got his master’s.

The result? During high school, he won world records (unbroken today) for the youngest bronze, silver, and gold medals at the International Mathematical Olympiad. Since then, he has won the Fields Medal in 2006, both the Royal Medal and Breakthrough Prize in Mathematics in 2014, has authored or co-authored over three hundred research papers, and is widely regarded as one of the greatest living mathematicians. The child’s real name, of course, is not “Adrian Seng.” It is Terence Tao.

Tao’s was one of 15 case studies from a book by researcher Miraca Gross, picked from 60 exceptionally gifted children from her landmark 20-year longitudinal study. He was the only one of those 15 children who answered yes to the question, “Do you think you’ve been able to perform at the limits of your abilities during your education?”

What happened to the other 14?

Why This Matters: Beyond the 1 in 10,000

In some sense, exceptionally gifted children like Tao — those who score above 160 IQ, four standard deviations above the mean, about one in 10,000 — are a niche topic. However, I would argue:

This is a very important 1/10,000th of the population, sitting at the cognitive forefront of the slice that drives technological and economic progress, and a group from which Nobel prize-winning scientists are often drawn.

The extreme case illustrates principles which apply to less-extreme cases. Most importantly, the social isolation caused by mismatch with age peers is common to many gifted children, but it is most acute and clearly seen in the exceptionally gifted.

The approach that best serves exceptionally gifted children is the same approach the CEP and I support for children at all levels: letting students accelerate to the level of their abilities in each subject. A child need not be a future Terence Tao to benefit from progressing at the pace that best suits their academic abilities, talents, and cognitive capabilities.

That “every student can advance as far and as fast as their curiosity and determination will take them” — a core principle of the CEP — proved a guiding ethos in Terence Tao’s education. And when researchers studied what happens to exceptionally gifted children when placed in different kinds of schooling environments, something striking emerged: acceleration was uniformly good, and retention was uniformly devastating.

Exceptionally gifted children have shown us the benefits of “unrestricted subject acceleration.” It’s academically ideal, of course, to be working at the level appropriate to you. But it’s also socially beneficial to be among peers who match your level, even if they’re a different age. In fact, I suspect it is socially good for most kids to have a few classes with kids 1-2 years older and younger than them; being age-segregated all day is artificial and seems unhealthy. The extreme case makes the lesson clear.

Part I: Who Are These Children?

There are two main sources I’ll be drawing from in what follows. First, Miraca Gross was a researcher who began in 1986 what would become a 20-year longitudinal study on 60 Australian children of 160+ IQ. In 1993, Gross published Exceptionally Gifted Children, a book focusing on 15 of those children with details about their lives and how they progressed. Gross’s work offers us invaluable insight into how best to raise exceptionally gifted children, and, in particular, into the benefits of radically accelerating their education.

Second, Leta Hollingworth was a psychologist who ran the Speyer School in 1930s New York City, whose students became the subject of Children Above 180 IQ Stanford-Binet, her published study of profoundly gifted children. With a population of ~7 million people during her tenure, New York was convenient for Hollingworth, offering a decent number of children for someone interested in studying the top 1 in 10,000 of the population to work with.

Early Development: The Pattern Emerges

So, what are these kids like? Among the 15 kids Gross wrote about in her book, the differences show up in very early developmental stages. The age when they sit up unsupported? Normal kids, 7 to 8 months; for these kids, it was 19% earlier. Age when they spoke their first word? Normally, 12 months; for Gross’s batch, 24% earlier. Crawling, walking supported, unsupported, and running: it’s basically 10-40% earlier than normal kids on average.

The biggest difference, though, is with reading, and it’s quite spectacular: 45% earlier. While the average Australian learns to read at age five, among the 15 kids, 5 learned to read at age one, 5 at age two, 2 at age three, 2 at age four, and 1 at age five.

What makes this even more impressive is that, for 9 of the 15, their parents say that they gave their child little to no help with learning to read. These children were picking up the skill naturally, practicing by reading street signs, grocery labels, the names of shops, and, for two of them, watching Sesame Street.

And when they were surveyed about what they enjoyed doing, reading was by far their favorite activity. 5 out of 15 said that reading is the most important thing in their life. All read an enormous amount, liking in-depth science fiction and high fantasy in particular, and of course, they tended to read books written for much older children.

Play: The Complication Instinct

These children like to do complicated things. If there’s a basic game, they like to add rules to make it more interesting and challenging. And the other children tend not to like that very much.

Hollingworth, too, noticed this among her students in the Speyer School, writing that the exceptionally gifted children “were unpopular with children of their own age because they always wanted to organize the play into a complicated pattern with some remote and definite climax as the goal.”

Among Gross’s 15, those who went into sports tended to do well — winning a championship, being offered a position on the state swimming team, a few things like that. Interestingly, however, they tended to pick sports that don’t require them to cooperate with others. Moreover, when asked to order eight activities “from most favored to least favored,” 40% put sports last and 13% second-to-last, including several of the most athletically talented. Given this low rating, Gross suggests that the pursuit of sports for these children may be driven less by enjoyment than by the need for peer acceptance.

The Friendship Mismatch

When gifted children struggle to relate to their peers, Gross says that this stems in part from how quickly their understanding of friendship develops. She argues that children grow through five stages of friendship. Initially, a friend is someone you’ll play with and let borrow your toys; next, someone to talk to about things beyond your play; third, someone you accept help and support from, but without yet thinking you have a duty to help them back; then, this help goes both ways — “We’re friends and we help each other.” Finally, at the fifth stage, this becomes “We can trust and accept each other completely.”

Importantly, Gross’s research shows that it is a child’s mental age (see footnote 1) that determines that child’s progress through these stages. As a result, she observes that extremely gifted children are beginning to seek the friend they can trust completely much earlier, at an age when their normal peers are still just looking for playmates. More than chronological age, socioeconomic status, or any other variable studied, sharing a similar mental age with a peer is the most important factor for children’s friendships.

Though an ideal companion for an exceptionally gifted child would likely be an equally gifted child of the same age, when those are one in 10,000, usually there aren’t any available. And so, unsurprisingly, often their best friends and preferred playmates are moderately gifted children 2 to 4 years older.

This creates problems. If an older friend is in a higher grade, then their time together at school is limited. Moreover, older children often face social pressure to not hang out with the wimpy little kid from a lower grade. Exceptionally gifted children face a double bind: classmates of the same age seek different qualities in their friends, and older kids seeking the same qualities grow out of reach.

The Boy and His Books

Nearly a century ago, Hollingworth saw that exceptionally gifted children’s heightened susceptibility to social isolation was not a matter of personality traits, but rather of an all-too-common mutual misunderstanding that develops among their less advanced peers. The tendency of highly gifted kids to play in a solitary way, she notes, can be explained as a coping strategy. They are not “unfriendly or ungregarious by nature,” she writes; “Typically, they strive to play with others, but their efforts are defeated by the difficulties of the case.”

She relates the story of a seven-year-old boy of IQ 178 who brought his favorite books to the class to show the others. “It’s great! Read these, you’ll see how great they are!” The other kids laughed at him, made fun of him, threw the books on the ground, and pulled his hair. The kid cried, “Grandmama, they just won’t read!”

For Hollingworth, his story is illustrative:

Other children do not share their interests, their vocabulary, or their desire to organize activities. They try to reform their contemporaries but finally give up the struggle and play alone since older children regard them as “babies” and adults seldom play during the hours when children are awake. As a result, forms of solitary play develop, and these, becoming fixed as habits, may explain the fact that many highly intellectual adults are shy, ungregarious, and unmindful of human relationships, or are even misanthropic and uncomfortable in ordinary social intercourse.

I suspect many of us know some people like that.

Part II: Tall Poppy Syndrome

At the Speyer School, Hollingworth investigated what approaches worked best for teaching highly gifted kids, moderately gifted kids, and also kids who struggle academically. She says that in the measurements they performed, those of 140 IQ are able to master subjects — described as “getting top marks” in a subject — in half the time that it takes the normal kids. Those of IQ 170, meanwhile, do so in a quarter.

This is a striking mismatch in learning speed between these kids and their normal age peers, and a larger difference than the ratio definition of IQ would predict. Perhaps in their earlier development these gifted children figured out effective study skills? Maybe they have more self-control? Maybe their intelligence manifested as an increased need for mental stimulation, and they were just more likely than normal to read the textbook at home because it’s interesting?

In any case, given the very large mismatch in learning speed, surely the schools will allow them to progress at this 4x speed. Right?

Well, at the same time they struggle relating to peers, gifted children also commonly face pushback from unsupportive educators. Gross offers a discouraging anecdote about one of her 15 subjects:

When the mother of 5-year-old Richard McLeod asked his teacher if he could be permitted to skip the reading readiness program because he had been reading since age two, the teacher angrily accused her of teaching the boy to read. ‘You leave him to me,’ she added. ‘It’s my duty to pluck the tall poppies.’

As mentioned, 14 of Gross’s 15 had learned to read before age five, the age when Australians enter kindergarten. Only a couple were allowed to skip the pre-reading exercises that the other kids were required to do; regrettably, this is usually the way early education goes for highly gifted children.

In another case, Gross discusses a kid who was doing eighth grade math in first grade when a new principal came in and canceled all the gifted programs, including that. He was forced down to second grade math next year.

The new principal was a politically alert young woman who was aware of the hostility of the Australian teachers’ industrial unions towards special programming for the gifted, and the disapproval of gifted programs openly voiced by a number of influential senior administrators in the state education department. She was also made aware by her new staff that they ‘had had enough of gifted children and special programs for the gifted’ which they felt had been foisted upon them by the old principal. [...] It would be ‘political suicide’ for her to establish gifted programs within her school.

Now, this is Australia, known for a strong egalitarian ethos and home to “tall poppy syndrome,” but things in the United States aren’t always better. I come from Palo Alto, where over the last decade they’ve cancelled honors classes and tracking.

The Sports Contrast

Gross mentions an interesting contrast with sports. Many educators seem to have no problem with scouting elite athletic talent and providing intensive support — one-on-one coaching, flexible schedules, advanced training opportunities. This treatment is “acceleration” by another name. So why is it different when the abilities are intellectual rather than physical?

Consider the investment: $30-40 billion annually on youth travel sports. Elite club teams costing more than college tuition. Scouts evaluating middle schoolers. High schools with “recruiting coordinators” and million-dollar facilities. Families relocating for better programs. All of this to develop athletic talent is celebrated. But let a mathematically gifted child skip two grades — costing nothing — and suddenly educators worry about things like “social-emotional development.” The hypocrisy is instructive: we already know how to accelerate exceptional talent. We simply choose not to do it for the minds most likely to cure disease, design infrastructure, or advance human knowledge.

Part III: The Results

Despite low support from the schools for doing advanced work, Gross’s subjects still achieved some fairly impressive scores. Of the 15 in her book, all were at least one year ahead in math and reading, with most at least two years ahead in math and three to four years ahead in reading. 5 children even exceeded 500 on the SAT-Math at age 12 or earlier, surpassing the average score for 17-year-olds applying to college!

The optimal environment for exceptionally gifted children is a class of equally gifted children of the same age that is paced for them. If that’s not available, then second-best is a class of moderately gifted kids somewhat older. And if that’s not available, then just skipping grades up to a class of normal kids who at least start the year at the same level. Since gifted children learn faster, they will probably be past these classmates by year’s end, but this is still better than the alternative — a class of normal kids the same age.

So, what was done with all 60 Australian children in Gross’s study? 33 weren’t allowed to skip any grades at all. 5 skipped one grade, 5 skipped two, and 17 skipped three or more grades by the time they left high school. (Given the general attitude toward gifted education down under, Gross herself found this last figure impressive.)

Who was permitted to skip was generally determined by whether a staff member had experience with or knew the literature on gifted education. Those who did tended to support the acceleration.2

And the results are in: Acceleration was uniformly good.

The Radical Accelerands: Three or More Grade Skips

Several cases of successful acceleration Gross discusses in her study are worth reproducing here at length.

17 of the 60 people were radically accelerated. None have regrets. Indeed, several say they would probably have preferred to accelerate still further or to have started earlier.

Gross quotes a 2001 paper by Lubinski, Webb, Morelock, and Benbow that reports similar findings from a study of profoundly gifted SMPY accelerands3:

Some of the children had an unfortunate start to school before their abilities were recognized. Others were fortunate enough to enroll in schools where a teacher or school administrator recognized their remarkable abilities and almost immediately argued for a strongly individualized program.

In every case, these young people have experienced positive short-term and long-term academic and socioaffective outcomes. The pressure to underachieve for peer acceptance [something one should never have in an educational environment! —JB] lessened significantly or disappeared after the first acceleration. Despite being some years younger than their classmates, the majority either topped their state in specific academic subjects, won prestigious academic prizes, or represented their country or state in math, physics, or chemistry olympiads.

The majority entered college between ages 11 and 15. Several won scholarships to attend prestigious universities in Australia or overseas. All have graduated with extremely high grades and, in most cases, university prizes for exemplary achievement. All 17 are characterized by a passionate love of learning, and almost all have gone on to obtain Ph.D.s.

In every case, the radical accelerands have been able to form warm, lasting and deep friendships. They attribute this to the fact that their schools placed them quite early with older students, to whom they tended to gravitate in any case. Those who experienced social isolation earlier say it disappeared after the first grade skip. Two are married with children. The majority are in permanent or serious love relationships. They tend to choose partners who, like themselves, are highly gifted.

Christopher Otway (pseudonym)

Chris is a young man of truly phenomenal ability. Testing on the Stanford-Binet L-M one month short of his 11th birthday revealed a mental age of 22 [IQ of 200]. Five months later he scored 710 on the SAT-Math. His remarkable talent in math and language was evident from his earliest years. By age four he was capable of fourth grade math.

Fortunately, the principal of Chris’s primary school had visited Johns Hopkins University on a Churchill fellowship. He had met several young people from the Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth, the SMPY, who had been radically accelerated [skipped three or more grades] and had familiarized himself with some of the research on acceleration. Accordingly, he was responsive to Chris’s academic and social needs.

While in grade 1, Chris was accelerated to work with fifth grade students for math and sixth grade students for English. The following year, he did math with seventh grade students. This proved so successful that at the end of his second grade year, Chris made a full grade skip to fourth grade, but took math with eighth grade. By age 12, he was theoretically enrolled in 9th grade, but took five subjects: physics, chemistry, English, math, and economics with 11th grade students 5 years older than him. He was extremely happy, loved school, and was popular with his classmates despite the difference in age.

In both his 12th grade years, he was one of the top scoring students in his state. He entered university at 16 years 2 months, graduating with Bachelor of Science (First-Class Honors) in computer science and mathematics at age 20.

Chris won a scholarship to a major British university and graduated with a PhD in pure math at age 24. Since then, based in London, he works for a worldwide consultancy assisting other companies with financial strategies.

Some may have opinions about the career choice in particular, but clearly he’s capable and is able to do what he wants.

Sally Huang

Sally was born in Australia to Malaysian parents. She scored 165 on the Stanford-Binet L-M at 6 years 11 months. Unfortunately, the psychologist stopped the test before Sally had reached her ceiling, and I believe her true IQ is significantly higher than this.

From her earliest years, Sally displayed phenomenal gifts in math and English. Her elementary and high schools, in a large country town, arranged a series of carefully planned and monitored grade skips coupled with subject acceleration. Sally entered second grade at age 6, fourth grade the following year, seventh grade at 9, and compacted the 6 years of high school into 4, graduating at age 13.

Sally’s path through school was assisted by her math teacher and the elementary school principal, who had a strong interest in gifted education, and has since earned a post-graduate degree in this field. She entered university, on scholarship, at 13.5 years old, as one of the top scoring 12th-grade students in her state — again, despite being much younger than the other ones.

Sally’s studies focused on the physical and mathematical sciences, but she also studied Chinese, Japanese, and music. She was allowed to skip first-year university math and enrolled in the science faculty’s second-year pure and applied math classes. Her enrollment in university required her to move to the city, and stay, during the week, in the home of friends of her parents. This gave her access both to the social life of the university and to her family. She gained a Bachelor of Science (First-Class Honors) at 16 years 8 months, and, like Chris Otway, won a full post-graduate scholarship to a major British university.

Sally gained her Ph.D. in theoretical physics at age 21 with five publications in major journals. She participated fully in the academic and social life of the university and had many warm and supportive friendships. She speaks fluent Chinese and Japanese, is an accomplished pianist, and holds a first-dan black belt in Tae Kwon Do.

The following year at a major European university, she completed a postdoctoral MBA aimed specifically at postgraduates with a science and engineering background and in 2004 accepted a management appointment with the firm in which she did her internship.

Sally is certain that acceleration brought her nothing but benefits:

If I had not been accelerated, I feel quite sure that I would have become quite frustrated, as indeed I often did at various stages and still do when I attend things like mixed ability language classes.... But the frustration in that case would have been prolonged and severe, having a detrimental effect not only on my love for learning but also on me as a person. Given the existing educational framework, acceleration was the best option for my particular situation and I certainly don’t feel that I’ve suffered any ill effects as a result; indeed, all the effects have been beneficial. But this is only because of the support and watchful eyes that were kept trained on my progress academically and as a person all throughout.

Certainly, if you’re doing academic acceleration, pay attention to how well it’s going. If the kid is feeling overwhelmed, then pull back. If the kid is feeling bored and finds age peers boring, then go forward, and just pay attention and update the plan as it goes.

Accelerated Two Years

The five young people who accelerated by 2 years report as much or almost as much personal satisfaction with their education as do the radical accelerands, although, like those who skipped three or more grades, the majority say they would have liked to have been accelerated further. Only two have taken Ph.D.s, but the remaining three have taken Bachelor Honors (research) degrees. Like the radical accelerands, they have entered professional careers, many of which utilized their remarkable abilities in math and the sciences.

In general, they have enjoyed satisfactory personal and love relationships. However, those who were retained with age peers until fourth grade or later tend to find socializing difficult. Exceptionally and profoundly gifted students should have their first acceleration in the early years of school before they experience the social rejection that seems to be a significant risk for such students retained in mixed ability classes. The skills of friendship building are first learned in the early years of school, and children who are rejected by their peers may miss out on these early and important lessons in forming relationships.

Accelerated One Year

The five young people who were permitted one grade skip are not deeply satisfied with their education. Their school experience has not been happy, and they would have dearly loved to have been accelerated further. After the euphoria of having new, challenging work, school became just as boring as it had been before the acceleration.

These children’s schools had been reluctant to accelerate them and were afraid that, while the grade skip had been successful, further acceleration might lead to social or emotional damage in later years. [Obviously the opposite of what the research appears to show. — JB] In two cases, the school told the children’s parents that they were concerned for the self-esteem... of other students, because the accelerated student was performing so much better than they were!

This group has tended to take undergraduate degrees and stop there. Because they have not had the experience of pitching themselves successfully and over a period of time at work that is truly challenging and demanding, they have no idea of the full extent of their capacities. Perhaps because of this, they have tended to enroll in undemanding academic courses and have consequently found university intellectually unchallenging.

It is with this group that a serious dissatisfaction with friendships and love relationships starts to appear. Two have had severe problems with social relationships.

The Non-Accelerands: The Tragedy

The remaining 33 young people were retained, for the duration of their schooling, in a lockstep curriculum with age peers in what is euphemistically termed the “inclusion” classroom. The last thing they felt, as children or adolescents, was “included.”

With few exceptions, they have very jaded views of their education. Two dropped out of high school and a number have dropped out of university. Several more have had ongoing difficulties at university, not because of lack of ability, but because they have found it difficult to commit to undergraduate study that is less than stimulating. These young people had consoled themselves through the wilderness years of undemanding and repetitive school curriculum with the promise that university would be different — exciting, intellectually rigorous, vibrant — and when it was not, as the first year of university often is not, it seemed to be the last straw.

Some have begun to doubt that they are indeed highly gifted. The impostor syndrome is readily validated with gifted students if they are given only work that does not require them to strive for success. It is difficult to maintain the belief that one can meet and overcome challenges if one never encounters them.

Several of the non-accelerands have serious and ongoing problems with social relationships. These young people find it very difficult to sustain friendships because having been, to a large extent, socially isolated at school, they have had much less practice in their formative years in developing and maintaining social relationships.

The Social Skills Development Crisis

People often say that children learn social skills in school, as if this were automatic and guaranteed. This is naive, especially for the highly gifted. A crucial part of social skill development is behaving in various ways and getting feedback. You try one thing, it doesn’t go so well; you try another thing, it goes better. You adapt and you iterate.

But if everything you try leads to rejection, then that’s not useful feedback. You’re not going to improve your skills, you’re not going to learn anything. At that rate, you’ll get a gifted child of 12 burdened with the social skills of a 9-year-old, who grows into an 18-year-old with the social skills peers had at 12. That 18-year-old will not thrive; more likely, he’s on track to blow professional opportunities due to interpersonal faults.

And even if you do accelerate the 12-year-old to join the high schoolers he’s naturally inclined to befriend, it may well be too late: he won’t have developed the social skills to relate to them, he’ll face the same rejection in a new crowd, and his social development remains as stunted as ever. Acceleration must begin early.

For gifted children in this situation, the best solution may be some kind of intervention therapy to teach social skills; absent this, the child may just avoid social situations entirely for the rest of his educational career, since they range from boring to painful. As an adult, if he’s fortunate, he can find a group as tolerant of weirdos as the rationalist community, where he can slowly develop his social skills alongside others who’ve faced the same trials.4

Giftedness and Success

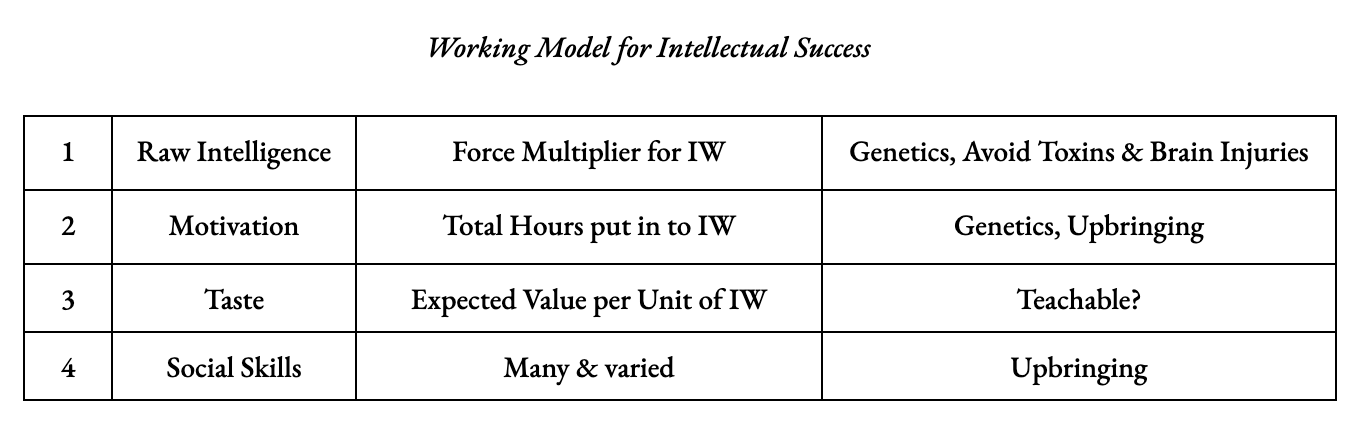

Synthesizing from many biographies of great mathematicians and scientists, a mentor of mine concluded that three qualities seem to determine success in those fields. The first is just raw intelligence, the variable we try to measure with IQ tests and other proxies. The second he called “obsessiveness,” or more generally, motivation. And the third quality is taste.

And there’s an obvious mathematization of this. Raw intelligence — or some part of it, depending on the task, whether working memory, the ability to make connections, or otherwise — is a force multiplier for the hours of intellectual work that one puts into a subject. Then motivation or obsessiveness determines how many of those hours one put in. And then the operationalization of taste is the expected value per unit of intellectual work of the projects that you choose to work on. For a formula, we can multiply these three together:

Intelligence × Motivation × Taste = (Rate of Value Production by Intellectual Work)

And you can also multiply by the length of a person’s career to get their lifetime output. Don’t die early — it tends to cause your career to go into decline.

Now, some scientific work today can be done by one lone person, a hermit. But a lot of it is working within a team, a lab, a biotech company. When you have to work with other people, social skills matter. They matter for getting good teammates, for getting onto good projects, and for directing the organization’s attention to better research directions over worse ones. This means that for many pursuits, we can add a fourth quality — social skills — for the complete picture of success.

So, if one wants to maximize such things, how do we do it? Raw intelligence seems mostly genetic, but we can avoid things that screw up your brain, the lead in the water and so on. Motivation is much less genetic, and I think has a large upbringing component we should be able to affect. And taste, my mentor believes, can be taught at least to some degree.

And finally, there are social skills. Upbringing is extremely impactful for that, as we’ve seen.5 There’s always an element of chance, of course; there are going to be at least a few kids who are in an environment that is not set up well for people like them, who nevertheless turn out well. But usually, when gifted children are stuck with same-age, normal peers most of the time, it’s not good.

It is crucial that we understand the effects of academic acceleration on each of these dimensions. The failure to accelerate exceptionally gifted children can have dramatic consequences for their motivation. Sitting in class with boring material, about things you already know, frustrated that you can’t get the teachers to let you do something else — the short-term effects for gifted children are bad enough, and the long-term negative effects may well be permanent.

Are we maximizing success? Given how important acceleration is to upbringing: Based on the acceleration numbers, I would rate our civilizational competency level: “Not even trying.”

Trying would look like allowing kids to take each subject at their appropriate level based on placement tests; this is the single most important change. One benefit of decoupling students’ progress across different subjects is that, if a student has failed a particular subject, it is less of a problem to hold them back in just that one class, while they can progress in others. That should make everyone involved less tempted to say, “Eh, let’s just shove that problem under the rug and promote them into the next grade anyway.” This in turn will mean fewer students in inappropriately high-level courses who don’t grasp the prerequisite fundamentals, and fewer of the problems that causes.

There are additional improvements that might be made. Taking students at a given level and grouping them by learning speed would be nice. If resources are available, 1:1 tutoring by great people is probably part of the optimal academic environment; AI might make that practical for everyone. But this one change would fix perhaps 80% of the problem.

What can we do as individuals and families? We can create extremely gifted children; some people here are working on that. Having done that, it’s a good idea to live near similar families, and/or create lots of siblings, so that these kids have peers that are similarly gifted that they can play with, be friends and stuff.

Then, once there are people nearby... Setting up microschools seems like a decent idea. I do suspect that online education and AI tutors are able to give you a good education without basically any other input. At the very least, I strongly suspect that telling one of these kids to spend one hour per day on Khan Academy, and then they can do anything else for the rest of their time, will likely give superior results to putting them through normal public school. We’ll see about that.

Given that education is handled, one way or another, then just try to ensure that they have the opportunity to make friends with kids who are amenable to them. If you must do normal school, then, okay; understand the children’s need for acceleration, and be prepared to push hard to get this for the children. And be prepared for the chance of the outcome where the school just refuses. Have some alternative in mind, like one of the above.

Perhaps your ambition is to produce and support exceptionally gifted children out of the hope of creating a world-shaking genius, one who will create medical or industrial advances that are worth billions of dollars to the world and are priceless to the individuals whose lives they transform. You can think of this as your way of impacting the world, and if you want, you can try to maximize this impact.

Yet you can also see the mission of supporting gifted children as simply the work of helping these children with incredible talents grow into happy, healthy adults with fulfilling careers that make productive use of them, and are well-positioned to carry on the mission to the next generation.

Reading through these stories of what befell exceptionally gifted children in schools filled with peers who scorned them and teachers who neglected them is very frustrating, and in some cases downright depressing. These stories are tragedies of untold pain and inestimable wasted potential.

We know enough now to improve gifted education for these children. The degree to which the past has caused them outrage is the degree to which we can enrich their future. That’s what I hope to do, and I hope many of you do as well.

A note on IQ scores, their limitations, and their uses

IQ scores above 160 are generally considered unreliable — the populations at those extremes are too small to establish robust statistical norms, and measurement error becomes significant. Childhood IQ scores, particularly extreme ones, also tend to regress somewhat toward the mean in adulthood as cognitive development evens out. We cite these scores not to mythologize intelligence testing, but because they serve as useful indicators: they identify children who would clearly benefit from accelerated instruction. The specific IQ numbers matter much less than what they can reveal: that extremely gifted children can operate way beyond “grade-level.”

To understand how we get numbers as high as 230 IQ, though, it helps to recall that the term “Intelligence Quotient” originally refers to the quotient of a person’s “mental age” divided by her chronological age. When we give children a range of cognitive tests — some involving anagrams, others rotating shapes — we find that their scores increase as they get older until age 18 or so, and that for any given age, we can find a corresponding average score. To evaluate a given child, we would aggregate her scores on several different subtests to find her resulting “mental age,” divide that by her chronological age, and that quotient, which they then multiply by 100 and round to an integer, is the “intelligence quotient.“ Thus, a six-year-old who scores as well as the average 9-year-old has an IQ of 150 — and when the six-year-old Terence Tao got the scores of a 14-year-old, that’s where the 230 came from.

Intelligence tests today default to the “deviation IQ” definition, where the average test score for an age group is set to 100 and an individual’s IQ is measured by how far above or below that average her score deviates, with a standard deviation of 15. Yet the classic “ratio IQ” definition is sometimes necessary for measuring very high scores. When an IQ above 180 is +5.3 standard deviations, which you only find in 1 in about 40 million people, finding a large enough cohort to test for a deviation-IQ average just isn’t practical; when Terence Tao’s 230 is +8.6 standard deviations, or 1 in 400 quadrillion people, a substitute for ratio IQ just isn’t possible.

As we’ll see, the ratio definition is a good prior for mental traits. If you’re wondering, “What is some trait of a child of a given age and a given IQ?”, just scaling up their age by the IQ number is a good first guess, if you don’t know anything else about it.

Terminology

“Exceptionally gifted children” is a term of art for children who scored above 160 on an IQ test, four standard deviations above the mean — something like one in 30,000. There are terms for “highly gifted”: 145+, three standard deviations. “Moderately gifted” is 130+, “mildly gifted” is 115+, “profoundly gifted” is 180+. And we might call 230 IQ “Terence Tao.”

Another determining aspect was that if a child’s gifts were primarily in math, they were more likely to be allowed to accelerate. If a child is highly advanced in math, it’s pretty easy to make the case even to a hostile audience that, “Look, the kid is correctly doing algebra problems. There’s no point in making them sit through pre-algebra.” It’s harder to vouch for the child with a highly advanced understanding of English. To “Look, the kid is reading books for much older people,” opponents of acceleration will just question whether they really understand what they read. Proving this understanding beyond doubt is much more difficult and effortful.

However, the fact that these factors are major determinants of the children’s acceleration makes this a nice natural randomization in the study. The kids who were accelerated 3+ years did very well, and the decision to accelerate some and not others was made mostly by factors external to their performance — so this is not simply a case of reverse causation. And we’ll also discuss cases where a child was doing badly, and then was accelerated, and started doing better, in ways clearly caused by the acceleration.

Gross uses the non-standard term “accelerand” in her work on gifted children. As she writes 2005 paper, “The term accelerant is often used to describe a gifted student who has been accelerated. However, correctly used, accelerant denotes an agent that instigates acceleration. The authors believe that accelerand is a more appropriate term to denote students who have been accelerated.”

I presented this in a joking manner, but actually I think it happens frequently. Scott’s surveys report an average respondent IQ north of 130; filtering the IQ column for 2-3 digit numbers, I compute an average of 137.

Incidentally, an obvious group to try would be Mensa, with members chosen by an explicit IQ test. The trouble with Mensa is the selection effect: the people who go to Mensa meetups are those who have a high IQ, and yet don’t have anything better to do. If rationalist stuff is sufficiently interesting and valuable, then maybe there’s less of an adverse selection effect. That’s the hope, anyway.

If autism is present, then upbringing is probably even more critical for whether a person grows up able to cooperate well with society.

“It’s my duty to pluck the tall poppies” 😯

> I suspect it is socially good for most kids to have a few classes with kids 1-2 years older and younger than them; being age-segregated all day is artificial and seems unhealthy.

Absolutely. This would have been a godsend for me as a kid who started puberty before anyone else in my grade. Wouldn’t have felt like such a freak if I’d had more older friends! And I think it would help the kids on the opposite end of the spectrum too.