Sputnik 2.0

The urgent lessons of China’s "genius-class" pipeline in the age of AI | Theories of Progress, 04

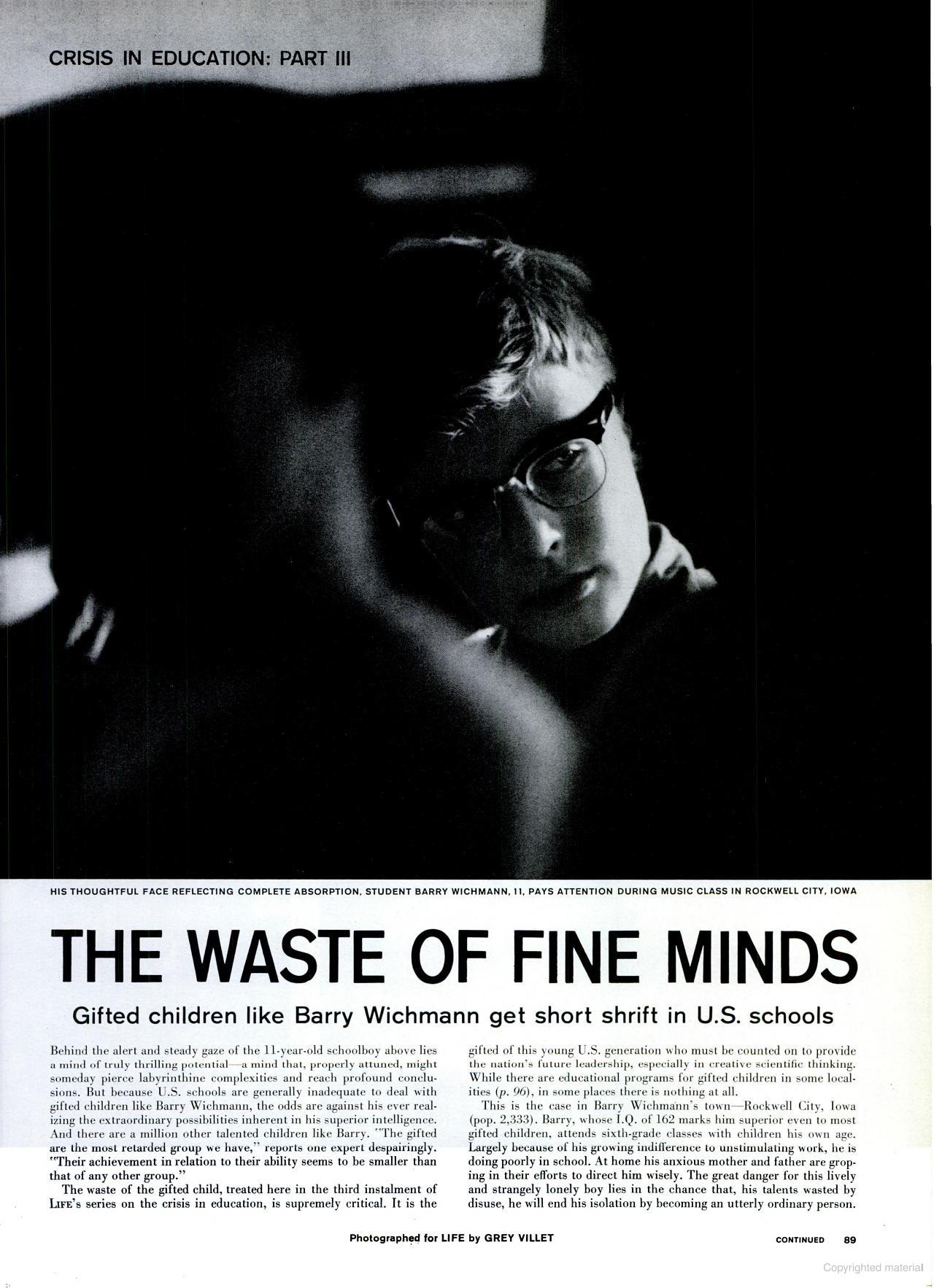

From Life’s April 7, 1958 issue.

When DeepSeek released R1 in early 2025, the model matched OpenAI’s performance at a fraction of the cost. American observers asked how a small Chinese startup could challenge Silicon Valley’s dominance. Last week’s viral Financial Times piece proposed an answer: China’s decades-long investment in its talent development pipeline.

DeepSeek’s team of 100+ engineers were almost all products of China’s “genius class” system — a nationwide network of intensive STEM programs that annually selects roughly 100,000 high-ability teenagers for specialized training. Nearly everyone on the team was an International Science Olympiad medalist. In 2025, of 23 students China sent to the Olympiads, 22 received gold medals.

The pipeline isn’t just producing talent for the AI race. The most recent Critical Technology Tracker report, published by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, reveals that China has replaced the US as the global leader in research output: China now leads in 57 of 64 critical technologies, 24 of which are considered “at high risk of a Chinese monopoly.” Even within the US, tech companies with “leading or strong positions in AI, quantum and computing technologies” employ more researchers who come from China (38%) than from the US itself (37%).

While continuing to welcome high-skilled immigrants is essential for driving our country’s STEM success, it is not enough for us to settle for only drawing talent from overseas. It is time to get serious about serving the eager gifted students at home.

An education crisis in a Cold War

The launch of Sputnik 1 threw the US federal government into a state of emergency. When the National Science Foundation Act was passed seven years prior, in 1950, the intention had been to advance scientific research and education in order to maintain America’s postwar dominance on the international stage. Now, in 1957, the US felt the urgent need to catch up. Out of this need came the National Defense Education Act (NDEA), which directed federal funding toward providing American students the educational support and rigorous training required to make America a powerhouse of science and technology.

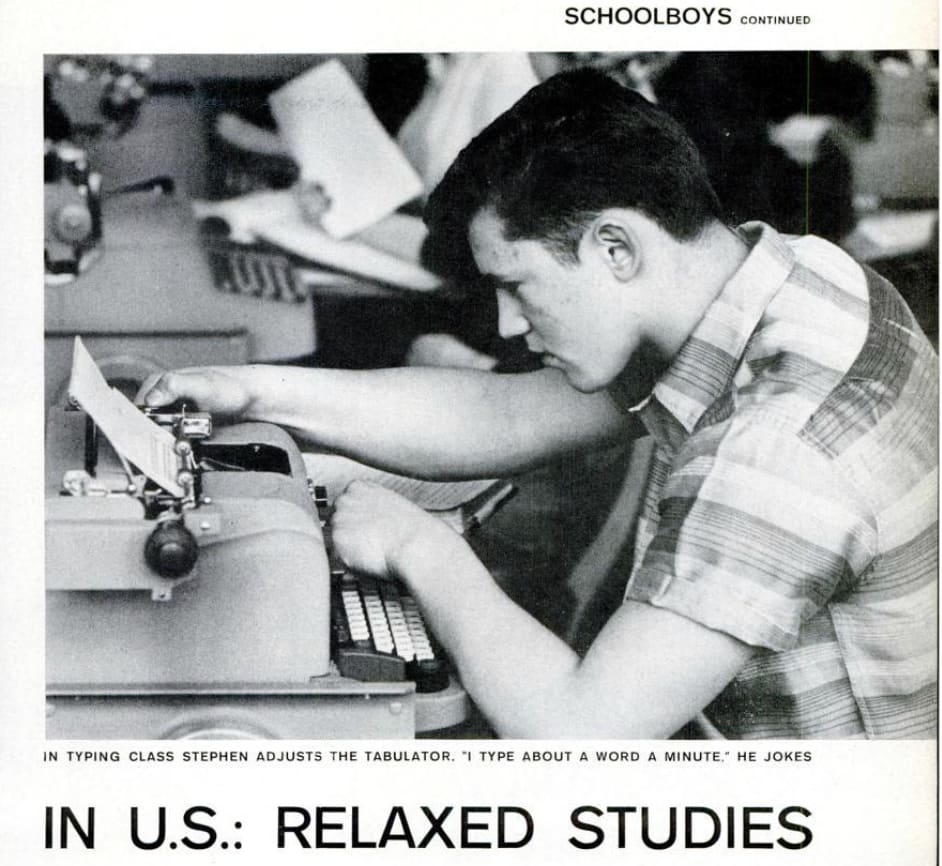

The public was concerned too. Popular media quickly seized on the idea that America’s school system, built around uniform pacing and broad access, was quietly neglecting all students, with the effects most visible among its highest-achieving. Newspapers and magazines warned that students were sitting in classrooms that prioritized fun, frivolity and anti-intellectual coursework over excellence, leaving future scientists, engineers, and innovators under-challenged. Few outlets captured — and amplified — this fear more effectively than Life magazine, which ran a widely read five-part series examining the educational aims of America’s public schools. The series profiled remarkable young students while sharply questioning whether American schools were capable of developing their potential. Through compelling storytelling and iconic photography, Life framed all children as the national asset most in need of intentional investment rather than blithe disregard, with special attention paid to the unmet potential of the nation’s brightest students. The message resonated with a public already rattled by Sputnik: American excellence will not be self-executing.

Yet just one decade later, members of congress wondered where all that initiative had gone. The country’s priorities had shifted; the fears Sputnik had inspired of being left behind had subsided, and were replaced by concerns about students struggling the most in school. While these latter concerns were noble, on the federal level, they came with a forgotten appreciation for the condition and needs of the gifted and talented.

A blueprint ignored: the Marland Report

In 1969, Sen. Jacob Javits (D-NY) introduced legislation, cosponsored by Rep. John Erlenborn (R-IL), that would require the U.S. Commissioner of Education to assess and report on the state of gifted education. His message to the Senate was the following:

“Today, a decade since the passage of NDEA, the Federal effort toward meeting the needs of the gifted and talented has diminished to the point that there is not one single Federal law or program devoting significant resources toward the education of gifted and talented youth, nor does the U.S. Office of Education employ anyone with responsibility in this area.”

It is hard to overstate just how comprehensive the report was — all 50 states were surveyed, numerous leading researchers were consulted, the longitudinal data of Project TALENT’s approximately 450,000 high school students were analyzed, and four thorough case studies were produced of model gifted programs in California, Connecticut, Georgia, and Illinois.

The report’s findings were striking:

Of the nation’s 1.5-2.5 Million gifted students, only a fraction received appropriate services

Differentiated gifted education was a low priority at federal, state, and local levels

Existing state laws were ineffective

Identification of gifted children was hampered by “apathy and hostility” among teachers and staff

Most strikingly, gifted children “can suffer psychological damage and permanent impairment of their abilities” equal to or greater than other underserved populations when not put in an appropriate education environment

In response, the report offered a number of specific recommendations:

Define gifted and talented children in federal law

Establish dedicated federal leadership and staff for gifted education

Provide categorical funding and support through existing laws like the Elementary and Secondary Education Act

Conducting national surveys of effective programs

Support research, personnel training, model demonstration projects, and state capacity-building

Prioritize identification and services for underserved groups

Initiate immediate activities to build infrastructure, including program development and evaluation

As a result, Congress established the Office of Gifted and Talented within the U.S. Office of Education (predecessor to the Department of Education) in 1973. This provided some federal coordination and modest grants for demonstration projects, teacher training, and program development — aligning with recommendations for leadership and model initiatives.

It also began limited categorical funding under the Education Amendments of 1978, with appropriations reaching about $6–18 million cumulatively in some periods, supporting special projects and addressing underserved populations to some degree.

Unfortunately, much of the early infrastructure was dismantled during the Reagan era, when federal education funding shifted from categorical grants to block grants. As a result, federal money for gifted education disappeared overnight.

Years later, in 1988, Sen. Javits introduced the Jacob K. Javits Gifted and Talented Students Education Act. It provided dedicated funding for research and demonstration projects; grants to states, districts, and institutions; and a national research center on gifted education.

However, the program’s scale remains woefully inadequate. Annual appropriations have typically hovered in the $13–17 million range (e.g., $16.5 million in FY 2024 and similar levels in prior cycles), a minuscule fraction — roughly 0.02% — of the overall federal K-12 education budget. This tiny investment supports only targeted research and grants rather than providing any direct or broad funding to local school districts for gifted programs.

Even more troubling is the fact that it faces perennial threats of elimination: it has been repeatedly targeted for zeroing out in presidential budget proposals (including in FY 2026) and House appropriations bills, and often requires sustained advocacy to keep it alive.

The Javits Act was a welcome win for advanced education. But it’s far from a national talent development policy. It’s a tiny, discretionary grant program that’s perpetually underfunded and repeatedly targeted for elimination in budget proposals.

Untapped potential

The lack of a coherent, intentional talent-development policy causes the US to systematically lose high-potential talent. This is especially true for high-achieving students (HALO) from low-income families.

One of the clearest illustrations of America’s talent loss comes from the landmark “Lost Einsteins” research by Opportunity Insights. By linking tax records, school data, and patent filings across more than one million individuals, researchers discovered something striking: children from wealthy families are far more likely to become inventors than equally high-performing peers from low-income backgrounds. The gap isn’t driven primarily by ability. It’s driven by exposure. High-achieving students from disadvantaged families often lack access to mentors, enrichment opportunities, and innovation networks that help transform raw academic talent into scientific or entrepreneurial breakthroughs.

The scale of this loss is staggering. The researchers estimate that if children from low-income families invented at the same rate as the wealthy, America’s innovation rate would quadruple.

Education research on high-achieving, low-income students reveals a parallel pattern earlier in the talent pipeline. Recent Fordham Institute research describes a “leaky pipeline” in which HALO students demonstrate academic excellence in early grades, but steadily lose access to the advanced coursework, enrichment, and institutional supports that drive long-term success. In Ohio, for example, HALO students are outnumbered by more affluent high-achieving peers by roughly three-to-one in elementary school, but that gap widens to six-to-one at four-year colleges and ten-to-one at highly selective colleges. These disparities are strongly linked to unequal access to opportunity: HALO students are 26 percent less likely to enroll in advanced middle-school math, 34 percent less likely to take AP, IB, or dual-enrollment courses, and 44 percent less likely to receive gifted services. Yet participation in these advanced opportunities dramatically improves outcomes, with even a single AP or IB course associated with a 29-percentage-point increase in four-year college enrollment among HALO students.

Much of this is the result of HALO students not being identified early-on in school. Research by Jason Grissom, Christopher Redding, and Joshua F. Bleiberg found that a high-achieving student in the top socioeconomic quintile is about twice as likely to receive gifted services as a student in the lowest socioeconomic quintile in the same school even when the students are achieving at similar levels in math and reading.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the United States does not lack talent — it lacks systems that reliably identify, cultivate, and sustain that talent. Countries with explicit talent-development strategies treat high-ability students as a national resource, investing in early identification, accelerated learning pathways, and mentorship pipelines that connect promising students to advanced educational and career opportunities.

A good place to start

To be clear, adopting a China-Style talent development system would likely be far from ideal in the United States. The human cost of China’s high-pressure system is well-documented, and it is a highly centralized state. We need something more, though, than the current hodge-podge of state and local policies.

A bill, called the Advanced Coursework Equity Act and championed by Rep. Cory Booker (D-NJ), is a good (albeit imperfect) place to start.

At its most basic level, the legislation creates a large federal grant program designed to help states and school districts expand access to advanced academic coursework. That includes Advanced Placement, International Baccalaureate, dual enrollment, honors classes, and gifted and talented programs. The legislation strongly encourages universal screening, which means evaluating all students for advanced learning opportunities rather than relying on teacher referrals or parent advocacy — two mechanisms that consistently favor families with greater time, information, and social capital.

The bill also recognizes something policymakers too often overlook: access alone is not enough. Many students who are capable of succeeding in advanced coursework never enroll. Some attend schools that simply do not offer advanced classes, while others face exam fees or tuition costs for dual enrollment that make participation financially unrealistic.

In order to be eligible for grants, states and districts receiving funding would be required to track who is participating in advanced coursework and who is succeeding once they enroll. That kind of data matters. By requiring better reporting, the legislation attempts to move conversations about excellence from rhetoric to measurable outcomes.

None of this makes the bill a silver bullet, though. It focuses heavily on middle and high school coursework rather than earlier talent development, where achievement gaps often begin. It does not fully address the teacher pipeline challenges that limit the availability of advanced coursework, particularly in rural and high-poverty schools. And, like most federal education legislation, it relies on grant incentives rather than establishing a comprehensive national strategy.

Still, progress in education policy rarely begins with sweeping changes. It begins with targeted reforms that address obvious failure points. Legislation like the Advanced Coursework Equity Act is a good first-step towards developing a national talent development policy.

American talent in the 21st century

If there is a single lesson running through America’s history of talent development, it is that we tend to act only when external pressure forces us to confront our complacency. Sputnik jolted the country into recognizing that intellectual excellence required cultivation. Today, the rapid acceleration of artificial intelligence and the emergence of global competitors like China present a similar moment of clarity. The question is not whether the United States has the raw talent to compete; the question is whether we are willing to build systems capable of finding and developing that talent.

The historical record shows that we have repeatedly identified the problem and repeatedly failed to sustain the solution. The Marland Report laid out a remarkably clear blueprint more than fifty years ago, warning that neglecting gifted students would carry both economic and human costs. The research since then has only strengthened.

The Advanced Coursework Equity Act does not solve all these challenges, and it wisely avoids copying the rigid and punishing Chinese talent system. What it does offer is a more balanced path forward — one that expands opportunity while protecting flexibility, local autonomy, and student well-being. By encouraging universal screening, increasing access to rigorous coursework, and demanding real accountability, the legislation sets us on the right path for future wins.

A true American talent strategy will require broader investments in early enrichment, teacher development, and mentorship networks connecting education to innovation and economic growth. But every durable policy architecture must begin with a strong foundation.

The AI era will reward nations that can systematically discover and cultivate their most capable minds. If the US hopes to remain a global leader in innovation and prosperity, it must move beyond episodic bursts of concern and toward a sustained commitment to developing talent at scale.