Politics and Neutrality in Public Schools

Sectarianism in public school classrooms is eroding trust and stifling student growth | Charting the Course

Guest Author Bio: Aaron Salt is the founder of ChalkForge, a school board consulting firm. He has founded a charter school, been elected to his school board, and worked in district administration. Aaron is the author of Govern Differently, in which he outlines his framework for academics-focused governance.

At the start of the 2025–26 school year, the San Francisco Unified School District told its teachers something that shouldn’t have been controversial: keep personal politics out of public classrooms. While the District’s restrictions on political expression are longstanding policy, its emphasis on enforcement is both new and overdue. Past SFUSD teacher trainings have commonly passed over these restrictions, and the prior school year saw numerous controversies involving staff political activism, including a misguided February resolution signed by 31 UESF members claiming that “educators who utilized their democratic rights to speak out against the [Israel-Palestine] war were repressed or harassed by school authorities.”

The District’s response to this resolution was unambiguous:

In the classroom, the District has a responsibility to regulate classroom activities and discussion to ensure that information is related to academic curriculum and that staff do not create undue pressure on students to agree with a staff member’s political views. When at work, our employees hold a unique position of influence over students in their care, and this influence is a privilege.

San Francisco is not a conservative district. That this guidance emerged there — and was treated as a reasonable clarification rather than a culture-war assault on teachers — suggests a growing recognition of something that should have been obvious all along: when teachers use public classrooms to advocate contentious views, they compromise their ability to educate.

As a charter founder, an elected board member, and upper-level district administrator, I have spent many hours walking the halls of primary and secondary schools and observing teachers engaging students across numerous classroom environments. One thing that has grabbed my attention is just how often the term “intellectual freedom” is used to justify all manner of classroom displays — political signs, religious symbols, band posters, inspirational quotes — that are wholly irrelevant to the curriculum. That these displays compete for students’ limited working memory is objectionable enough, but they do more than distract from instruction. They signal to students what their teacher believes, and students notice.

I’ve heard directly from students who were concerned about grade retaliation because their teachers were overtly displaying opinions different from their own. Whether the teachers would have actually retaliated is beside the point — the students’ perception created a barrier to genuine discourse and exploration. When exposed to political and religious content, students infer the “right” beliefs in a given classroom and modify their behavior accordingly. Teachers must build rapport with their students to engage them in meaningful instruction. Yet when, in the name of self-expression, a teacher promotes a cause or candidate that students do not support, that rapport erodes, and the classroom now disincentivizes the agency and independence of thought for which we prize in public education in the first place. That’s the opposite of intellectual freedom.

Here lies the great irony and central confusion: what many call “intellectual freedom” in these contexts is really the freedom of teachers to express themselves. But genuine intellectual freedom in K-12 education should mean the freedom of students to learn, explore, and form their own views without undue pressure. And when schools allow teachers to invoke the former sense of “intellectual freedom” for themselves, they actually make it increasingly difficult for them to accomplish their jobs as educators.

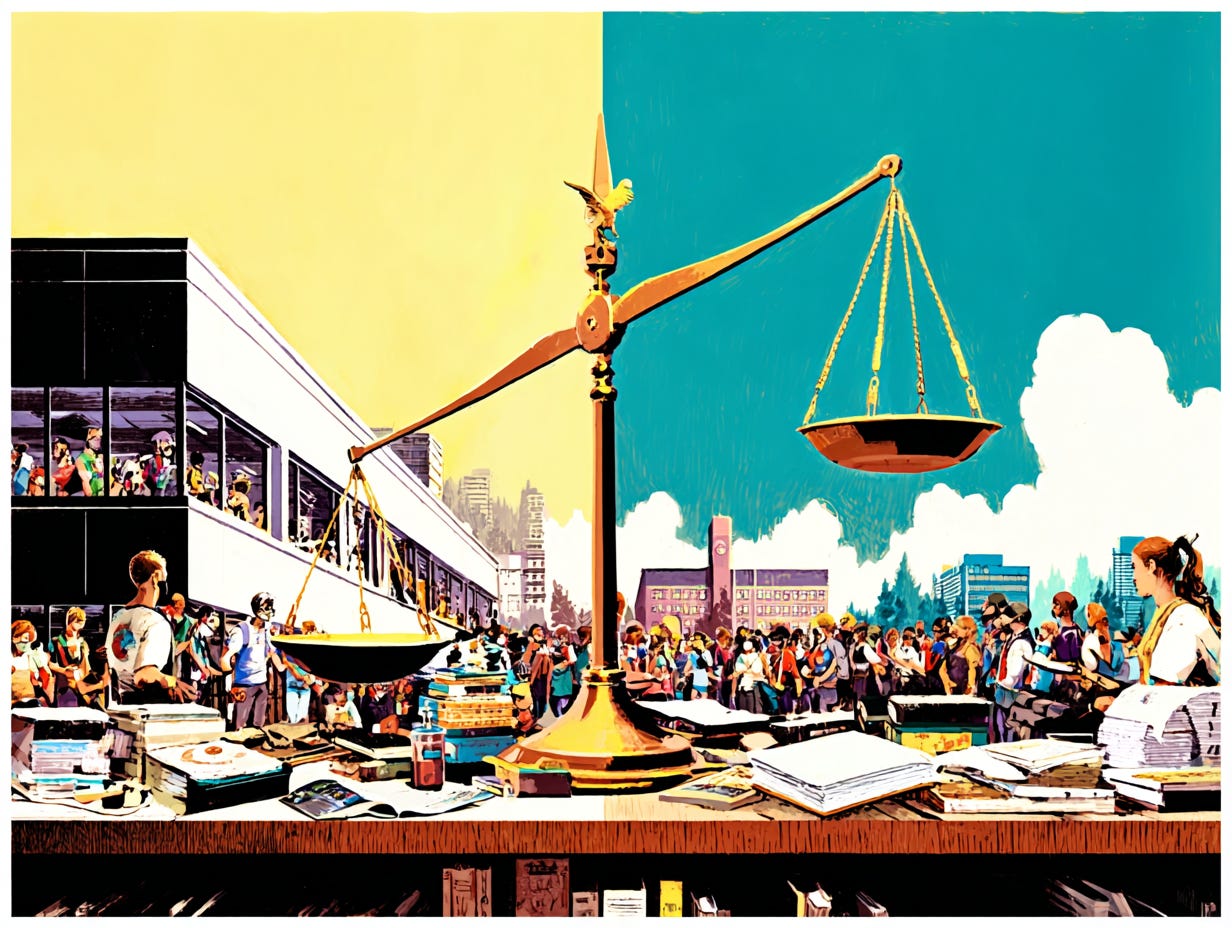

The catalyst for upholding the intellectual freedom we care about is promoting neutral classrooms in public schools. Neutrality avoids the conflict between teachers’ expression and students’ intellectual freedom, actually protecting the latter rather than stifling it. To foster civil discourse in line with its mission, public education must give students the freedom to learn, study, and think about things in different ways and from multiple angles. There must be freedom to investigate and draw differing conclusions for us to have the opportunity to disagree civilly. The commitment to genuine neutrality ensures that we are training students’ capacities for judgment, not tipping the scales of what those judgments should be.

This approach isn’t radical or impossible to implement. When my board worked in partnership with the district administration to establish neutral classroom guidelines — limiting displays to U.S. and state flags — we received fewer than five comments over three months. No media controversy, no teacher rebellion. It was a non-issue because the guidelines were presented correctly: as a way to promote student success by removing barriers to learning.

When teachers fail to internalize the value of neutrality for intellectual freedom, they risk putting undue pressure on students to endorse views on the basis of influence rather than reasoned reflection. When public schools themselves fail to internalize the value of neutrality, we risk a case like Mahmoud v. Taylor.

When Montgomery County, MD — one of the nation’s most religiously diverse school districts — introduced LGBTQ+-inclusive storybooks into its elementary curriculum in Fall 2022, the district offered families an opt-out policy, which is common for sex education instruction nationwide. Families would be notified in advance when lessons would feature this material, and parents could opt their students out of those lessons. Then, in March 2023, citing administrative burden from the volume of requests, it revoked that opt-out policy.

The volume of requests alone should have signaled to the district that it was betraying the nonsectarian spirit of public education. The plaintiffs — a diverse collection of Muslim, Roman Catholic, and Orthodox families — objected not to the books’ mere presence in school libraries, but to mandatory instruction using materials they believed promoted contested moral conclusions: teacher guidance explicitly instructed educators to “disrupt” children’s “either/or thinking” about biological sex. These parents weren’t trying to ban the books or prevent other children from reading them. They were asking for the same opt-out accommodation they’d been offered before, an accommodation that — again — is commonplace for sex ed instruction.

The Court ruled 6–3 that the district’s refusal to allow opt-outs violated the parents’ right to free exercise of religion. Justice Alito, writing for the majority, found the books “unmistakably normative” — “designed to present certain values and beliefs as things to be celebrated, and certain contrary values and beliefs as things to be rejected.” By rescinding its opt-out policy, Montgomery County schools were stifling students’ intellectual freedom by mandating morally prescriptive instruction unrelated to curriculum. Had the District appreciated the value of neutrality for fostering critical inquiry unburdened by influence, this case would never have reached the Supreme Court.

Parents trust that their impressionable children are learning to read and do math in an environment where political and religious views are not thrust upon them. When schools and teachers betray that trust, classrooms cease to honor their mission.

If we want students to grow and learn, we must return public classrooms to a neutral state. The best support we can offer teachers in completing their mission as educators is to break down the barriers that would put them in conflict with their students or distract those students from what they need to learn. Likewise, the best support we can offer students on their path to academic success is to encourage them to read about different topics, investigate all sides of an issue, and draw their own conclusions. We don’t need to choose between intellectual freedom and ordered classrooms — neutrality gives us both. When classrooms become spaces where ideas are explored rather than prescribed, where students aren’t decoding their teacher’s politics or navigating ideological minefields, we create the conditions for genuine learning. We should strive to support true, authentic intellectual freedom from a foundation of institutional neutrality. The goals of public education warrant nothing less.

I don't think this is possible absent agreement on what education means across factional loyalties; what sort of information is apolitically important seems to be contested. We might have enough notional agreement for a very minimal reading-writing-calculating education, but that wouldn't justify most of teachers' salaries or serve their day care / carceral function very well.

Mostly disagree with this piece. To the extent that there is a problem here (and I'm not sure it's a very significant one), the answer is not to tell teachers that they need to hide their political beliefs; it's to make sure that they assign readings they disagree with as well as ones that they do and to welcoe (and more than that encourage) students to disagree with them.

I'm completely fine with my kids having teachers who are not shy about sharing their political beliefs as long as they welcome disagreement. And it's not that hard to make it happen. It's simply about principals making it clear the kind of environment they want and also making an effort to hire teachers with different perspectives.