Attacks on Excellence: The 2025 Year-End Roundup

“Isn’t there anyone who knows what school is all about?” | Attacks on Excellence, Issue #5

Disarray in the Department of Education

DOGE-be-gone. When 90% of staff at the Institute for Education Sciences was terminated, the fate of education research and statistics looked grim at ED. Now the administration looks to undo some of the damage, with the aim of “reforming IES to make research more relevant to student learning” and figuring out “how to collect data more efficiently.” But too much damage has already been done at ED’s statistics and research wing, as Jill Barshay has documented over the course of this year. Her comprehensive article is worth a full read. EdWeek reports on where ED’s different programs will move as the Trump admin attempts to downsize it, for those interested.

To read more from us on this issue, check out our previous coverage of what DOGE was up to at the Ed Department.

Gambling with the schools. New education flashpoints have emerged in Chicago, where tensions over tough choices in the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) were already high, after a letter from Trump’s Education Department sparked an ongoing legal and political battle between city (and Illinois) authorities and Trump’s government. On Tuesday, September 16th, ED sent a letter to CPS identifying two alleged failures to follow federal civil rights law. CPS would need to overhaul both the “racially exclusionary” Black Student Success Plan it had launched in February and its guidelines on transgender and gender-nonconforming students, or else risk losing millions grant funding previously awarded under the Magnet Schools Assistance Program. But since its Black Student Success Plan and guidelines on transgender and non-conforming students were developed to satisfy Illinois state law, CPS was in a bind. Come Tuesday, September 23rd, the Trump administration canceled $23 million in grants.

The story looked similar in New York. On that same Tuesday, the Trump Education Department sent a letter identifying an alleged “civil rights compliance issue” with the city’s guidelines on transgender students’ participation in sports and access to bathrooms aligned with their gender identity. When city education officials did not comply with the administration’s requirements by the following Tuesday, September 23rd, millions in grant funding to NYC magnet schools were canceled. As of now, a federal judge has allowed schools to use $12 million in “carryover funds” from the prior year’s funding.

Bunk metrics and test skeptics

Bad incentives and mass accommodations gaming in the (elite) schools. Disability accommodations have given countless Americans access to educational opportunities and facilities that would have been otherwise unreachable. But, it is also an unsettling fact that today disability accommodations at elite colleges and universities have completely outstripped expectations. A recent piece in The Atlantic shares some shocking figures: the number of students qualifying for accommodations at UChicago has increased more than 3x in 8 years, and at UC Berkeley 5x in 15 years; more than a fifth of students on the books at Brown and Harvard are disabled, and at Amherst more than a third. Since the 2008 amendments to the ADA broadened the scope of conditions that could be construed as disabilities, including mental health conditions such as ADHD, anxiety, and depression, and as the pressure to succeed in top schools has increased unabated, students have been steadily driven to receive the kind of diagnosis that can grant more time and higher scores. Although many advocates remain more concerned about those not yet receiving accommodations who need them, it is clear that “accommodations have become another way for the most privileged students to press their advantage,” and our most prestigious institutions have led the way.

The evergreen debate over standardized testing. Inside Higher Ed recently ran a piece by Saul Geiser arguing that the SAT is a weaker predictor of college performance at the University of California than high school GPA. Geiser argues that the research favoring the SAT over GPA doesn’t consider “background factors such as family income or race” that correlate with higher SAT scores, and that when these factors are accounted for, the predictive weight falls for SAT scores and increases for high-school GPA. But Geiser’s case against the SAT is not new, and last year saw both a formal critique of Geiser’s work and an excellent, more approachable (and underappreciated!) rebuttal from Michael Weissman. Weissman points out that Geiser’s data actually supports using SATs more, not less, if one is interested in admitting capable students of low socioeconomic status, and this conclusion maps on neatly to the rationale given by the many colleges and universities, such as MIT, that are reinstating their standardized testing requirement for admissions.

Yet even long before students are applying for college, standardized assessments offer students and their parents the benefit of a clear picture of how much they have learned and where they fall behind. However, the slow pace at which some states release their yearly test scores often means parents lose valuable time to intervene and seek help for their students. It took the New Jersey Department of Education nine months to release the results of its statewide 2024-2025 NJ Student Learning Assessment, at which point parents had already missed out on the chance to seek extra support over summer vacation and for the beginning of the year. Parents can’t advocate for kids to get the help they need when states don’t release the data. Already, a full 88% of parents believe their children perform at grade level in reading and math, although only 30% of eighth graders score proficient or better on the NAEP. As pervasive grade inflation makes report cards less reliable signals, parents and students are in even greater need of unbiased standardized assessments to get an accurate picture of student learning.

That said, it doesn’t help that the NJDOE has been slow to answer whether its newly announced 2025-2026 statewide assessments in reading and math would be comparable to those in previous years. If the “adaptive testing” introduces a “new baseline,” there will be one more obstacle preventing a clear picture of student learning in New Jersey.

Too many state proficiency standards continue to slip…

… in Alaska, New York, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, Kansas, and Illinois, writes Karen Vaites over at her excellent School Yourself Substack. When states choose to lower their “cut” scores (i.e., lowering the threshold for what it considers “proficient” performance on its state assessments), they only make it more difficult to identify and help their lowest-performing students. Trying to track academic performance over time also gets muddier as a result, as certain cohorts see their scores artificially inflated compared to previous ones. Thomas Toch and Bella DiMarco write for FutureEd about how data from new NAEP scores highlight these “standards gaps” that have emerged in many states. After a decade of declining student performance, post-COVID trends indicate that the biggest learning losses are occurring among the lower-performing students, and so it has never been more imperative to have a crystal-clear view of where, exactly, those students are at academically.

Cutting through the Illinoise. The story in Illinois illustrates how even well-intentioned reform efforts can founder in the face of system-wide incentives to get scores up. When the Illinois State Board of Education released a comprehensive literacy plan in January 2024, it was the culmination of a campaign begun in 2022 to oust “balanced literacy” in favor of evidence-based reading instruction. When state reading scores improved, education officials organized a listening tour to begin work on a “comprehensive numeracy plan” that could do the same for math scores. But Illinois has recently proposed lowering the proficiency cut scores that separate students into categories of proficiency. Since this proposal was approved, reading proficiency has improved from 39% in 2024 to 52% in 2025, and math proficiency has risen from 29% to 38%. However, since these proficiency rates are based on the new, more lenient cut scores, a true comparison is quite difficult, leaving us skeptical about how much we can glean from this data.

For a story about a better approach, read about Virginia’s decision to elevate its cut scores in The 74.

An uncertain future for education in New York City

The new mayor. Zohran Mamdani will be Mayor of New York City soon, and his vision for education policy and the personnel who will carry it out remains somewhat uncertain. Mamdani’s campaign lacked a clear plan for education in New York, and the details he did offer included duds like ending kindergarten gifted education programs. His opposition in the mayoral race hoped to capitalize on Mamdani’s wobbly education stances; Cuomo in particular benefitted from aligning himself with gifted ed, and when the Mamdani campaign didn’t invite the gifted education advocacy group Parent Leaders for Accelerated Curriculum and Education (PLACE) to an education policy roundtable, PLACE endorsed Cuomo during the mayoral race.

The plan. According to Chalkbeat, so far Mamdani and his youth and education transition committee have focused on affordability and social justice — as they did during the election — highlighting policies like free childcare and tapping personnel from school integration advocacy nonprofits. When it comes to how Mamdani will manage the school system, what we know now is that he intends on ending mayoral control of the NYC schools, or at least significantly rolling back the traditionally centralized power structure. The purported aim is to democratize the schools and thus make them more responsive to the needs of their local populations. Local control, however, can lead to its own problems in the schools. Chalkbeat recently solicited dozens of “bold ideas” for Mamdani and his education team, though none mention curriculum reform efforts like those that were implemented during the Southern Surge.

Current equity frameworks still a hurdle for effective teaching, student standards, and research

Grading the research. Two recent surveys reveal how equity-first ed research and reform efforts have been failing teachers and their students. The late August report from David Griffith and Adam Tyner at the Fordham Institute shows that most teachers consider four practice characteristic of “equitable grading” — no zeros for never-completed assignments, no participation grades, no lateness penalties, and no assigned homework — “harmful” or “very harmful” to students’ engagement in learning. Despite these teachers’ judgments, these practices are commonplace in over half of the nation’s public schools. More recently, though, a study by David Marshall, Andrew Pendola, and Tim Pressley revealed just how disconnected education research is from the daily reality of teachers in American schools. Whereas ed research continues to prioritize “questions of identity and justice,” teachers remain primarily concerned with “behavior and discipline, mental health and well-being, parental involvement, and teacher retention.”

Order, not more “theory,” in the classrooms. Meanwhile, the case for “restorative justice” — perhaps the most popular family of policies among school discipline reformers — continues to get weaker and weaker. Consider a recent video from The Bell’s Miseducation podcast that looks into restorative justice practices in New York City. When students’ “eyes glaze over” and phones come out in restorative justice circles, we are told, this is not a warning sign about the efficacy of the practice itself, but an indication that even more time must be devoted to teaching students about restorative justice. This, of course, ultimately means less time devoted to other topics and activities. All too often, the counterpart to a rosy-eyed approach to school discipline is an insistence on reframing reform failures as failures of general investment or buy-in to the controversial reforms themselves. If “Tier 2 conflict resolution” is ineffective and disengaging, then allocate even more time for “Tier 1 community-building.” When the conflict resolution fails to improve, just rinse and repeat. To read more about the need to ensure orderly classrooms, read Neetu Arnold and Daniel Buck’s recent article in City Journal.

Curriculum Woes

Georgia on our minds, too. Karen Vaites offers her thoughts on Georgia’s failure to get high quality, knowledge-rich curricula into district hands. Although ostensibly committed to curricular reform à la nearby Southern Surge states, the Georgia Department of Education board recommended several basal programs by large publishers alongside programs of higher quality. Most districts, unfortunately, fell for the high marketability of the big players’ products. While some districts (like Marietta City Schools) have made impressive gains thanks to choosing programs like Wit & Wisdom and UFLI — two high-quality programs — most districts working from the GDOE’s long list of recommended materials were susceptible to the large publishers’ flashy campaigns. Districts need to be firmer and more exacting with their recommendations, for, as Vaites laments, “when state lists are a mixed bag, districts pick the weaker stuff.”

Constructivism in Seattle. In the Seattle Times, Barbara Oakley reviews the dismal track record of “constructivist” theories of learning that sideline practice and mastery in favor of demonstrations of “conceptual understanding.” Even when they fail to offer the right answer, students often earn credit for being able to explain how they arrived at the answer they gave. While advocates defend this practice by claiming understanding is the true goal of education, the science of learning shows us that the brain system responsible for explanations and descriptions is different from the one responsible for retaining knowledge through practice and memorization. It may seem like a focus on “conceptual understanding” prioritizes critical thinking and problem solving, but in fact understanding relies on a high degree of automaticity when recalling facts and skills. If such a focus comes at the expense of the structured practice that builds retention, then students won’t be in a position to “understand” the content at all. See Oakley’s full piece for how Washington is falling into the same trap as Finland, New Zealand, and Taiwan, who have each suffered for abandoning knowledge-rich curriculum.

Perhaps this should set off some alarms when we hear that SFUSD’s new K-8 curriculum focuses on “understanding the ‘why’ behind the math.” Speaking of San Francisco…

California Dreamin’

SFUSD students can’t catch a break. Last year, voters overwhelmingly supported returning Algebra 1 to eighth grade. For a full decade, students were denied critically important math instruction out of a misguided pursuit of social justice. But with this vote, the school board committed to offering Algebra 1 in every middle and K-8 school in the district beginning Fall 2026, and the catastrophe had an end date at last. Execution, however, is everything. Despite its initial publicized plan, which touted Algebra 1 course offerings “during the school day” throughout the district, the school board now seems unwilling to guarantee live, on-site algebra instruction. For half of the city’s middle and K-8 schools, students are currently limited to taking Algebra 1 in an online or accelerated summer format, and board representatives won’t answer whether this will change for the 2026-27 school year. Many education officials and school reform advocates first opposed eighth-grade Algebra 1 in 2014 on the grounds that tracking was inequitable. Yet now, those criticisms are ringing hollow after years of restricting access to high-quality, on-site instruction has produced a new kind of inequity, as numerous San Francisco students are left with only weak, self-directed video compilations. These students deserve better — read the full story from Ezra Wallach in The San Francisco Standard.

While the hotly debated plan to require ethnic studies for graduation has idled — that plan relied on new funding, which is rather scarce given the deficit — other changes in the district seem bittersweet. When school reconvened in Fall, district leaders put a collective foot down about teachers’ political speech in the classroom, but this has caused friction between said leaders and the teachers union. This conflict mirrors the national debate over politics in the classroom, as many California educators now report that they avoid teaching once-central civics lessons out of the fear of discussing any topic with a whiff of politics. Meanwhile, relations remain frayed between the SFUSD and the SFPD, which The Voice of San Francisco details these and more problems in an excellent, thoroughly troubling three-part series.

UCSD comes clean, but the problem goes beyond The Tritons. UC San Diego unleashed a firestorm of commentary when its faculty senate published a report on the rapidly growing mathematical unpreparedness of their student body. The best article on the whole affair is Kelsey Piper’s piece in The Argument. The problem goes beyond UCSD’s ever-expanding remedial math classes, though. Many of those students got good grades in advanced math classes in high school, leaving many wondering what, if any, checkpoints or safeguards remain on rigorous assessment of student proficiency. See Rose Horowitch’s article in The Atlantic for more interesting commentary. The Wall Street Journal Editorial Board thought it was pretty important, too.

A turning point in the war against phones

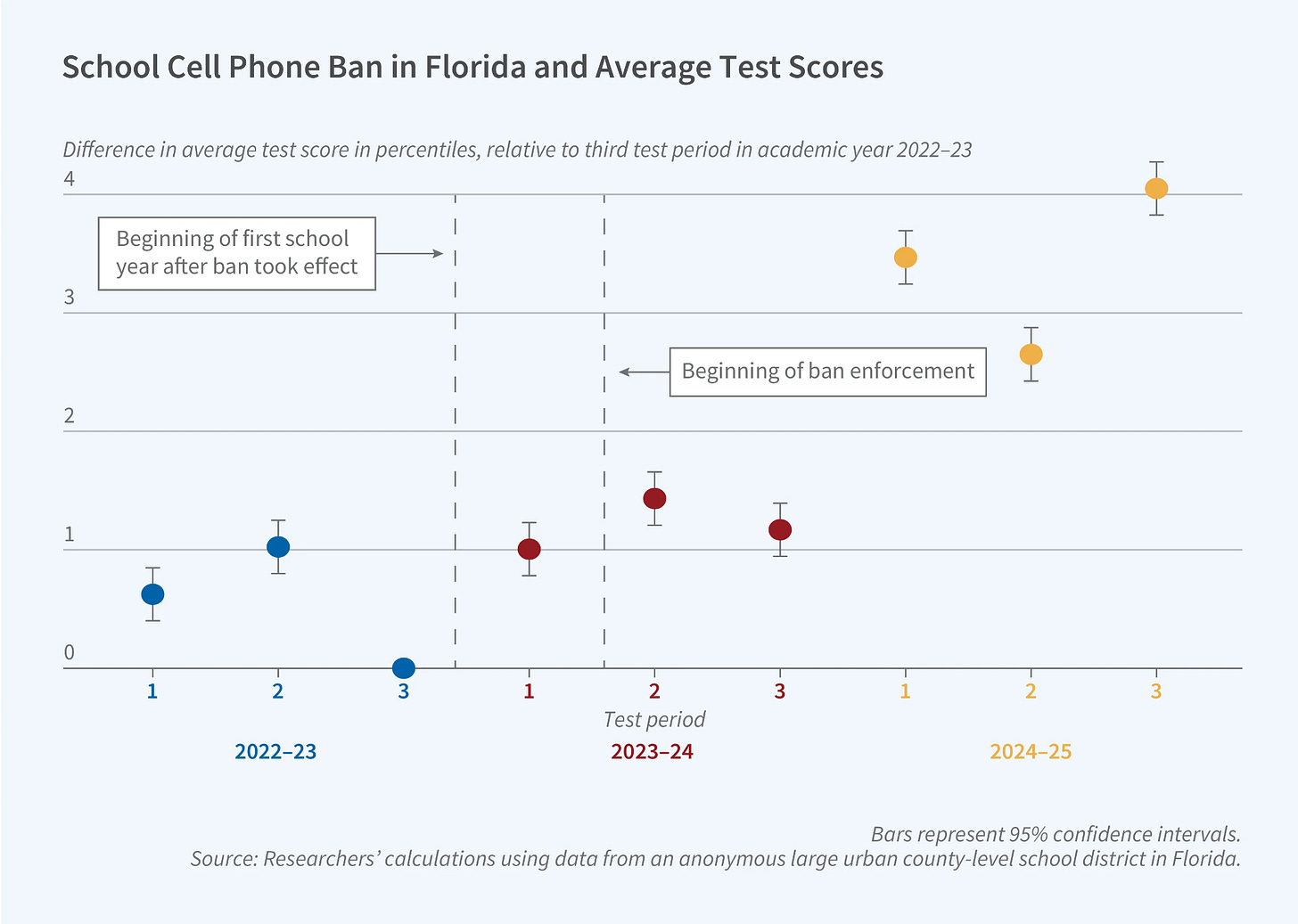

Telephona delenda est. American schools are finally getting serious about banning phones. No longer is it any secret that phone use dramatically undermines student learning and well-being. When students can’t even focus on lessons or schoolwork because of constant distraction and anxiety, the fight for evidence-based pedagogy and knowledge-rich curricula can feel like a lost cause. But the tide might finally be turning. Half the states in the country have now implemented cell phone bans in schools, and five more states are actively considering proposed bans. The early results are as promising as they are intuitive. In Florida, the first state to enact a phone ban in K-12 public schools, test scores are already improving and absences are falling.

Tremendous credit is due to Jonathan Haidt, whose work on the harms of phones in schools — in particular his bestselling book The Anxious Generation — is directly responsible for setting the agenda for politicians on both sides of the aisle to step up.

Keeping track of bad ed

Thanks for reading this year’s final issue of Attacks on Excellence. Click here to read our previous issue on New York’s bad statewide math instruction agenda, and look out for our next issue coming soon.

Have a story for the Attacks on Excellence series? Submit a report [here] or email centerforedprogress@gmail.com (subject: Attack on Excellence).

As arguments for a content-rich education go, "catching classical references" isn't my favorite... but doing a literal toothpaste spit-take when I saw "telephona delenda est" really WAS a high point of my evening.